Economics Is a Science, Part 3

Common characteristics with other sciences

This will be the part of the series that most directly addresses the question of how “scientific” economics is. To do this, we’ll look at important features of science in general, and see how those features appear in economics (or don’t). Some of the features it has make it look even better than physics, while others make it clearly worse. I think you’ll agree that economics is very respectable as a scientific field when all of the evidence is taken together.

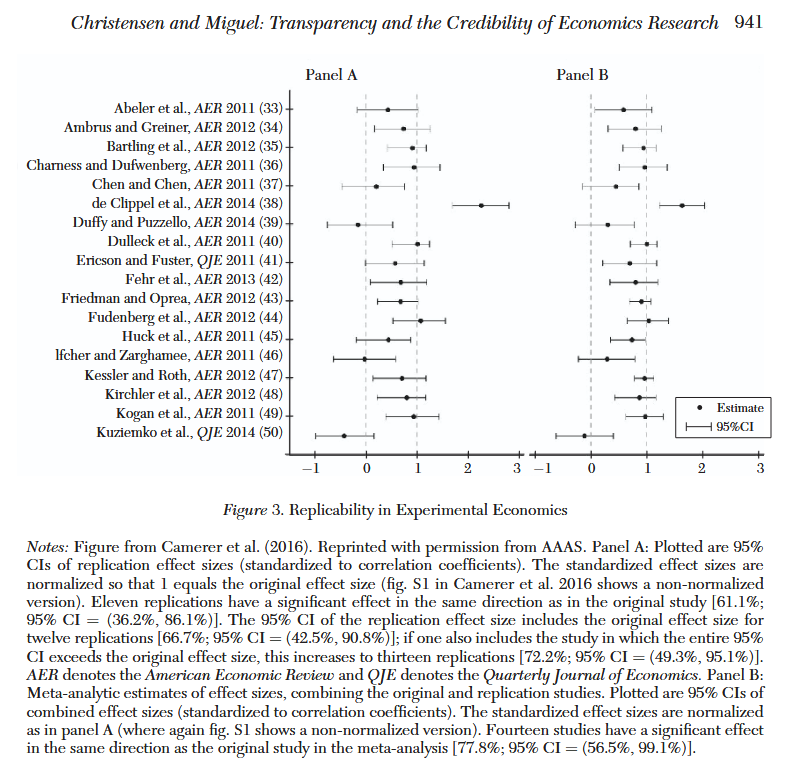

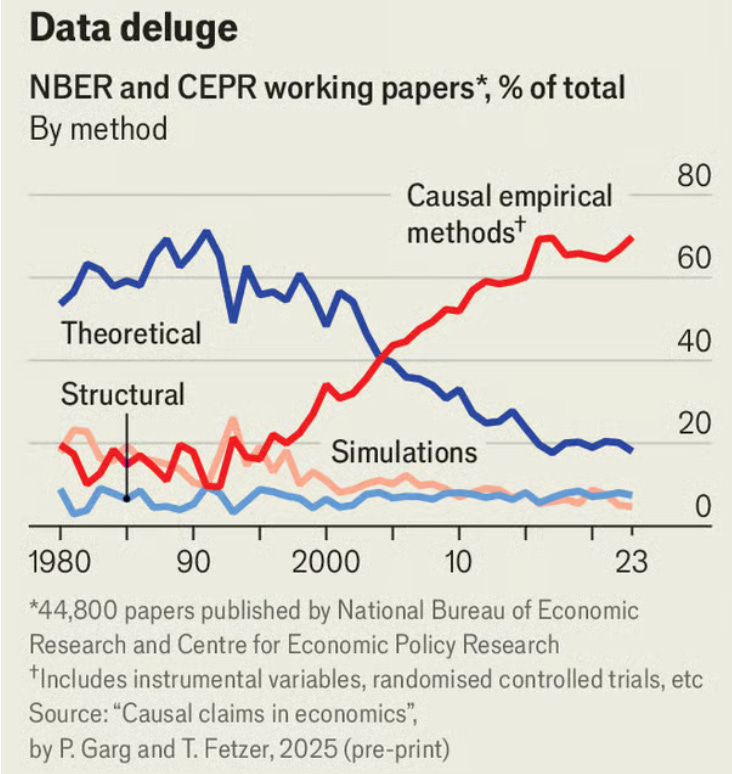

Some might consider this something of a word game, with the question of whether economics counts as a science depending largely on how we define science. This is true, but it doesn’t defeat the purpose of this text. It’s still worthwhile to explore whether economics fits different views of what can count as a science. To give the most obvious example, empiricism (the idea that all knowledge is derived from evidence through sense experience) is at the heart of almost any conception of science. The previous post showed that economists have a wealth of empirical tools. These have come to make up the bulk of work in economics:

We’ll begin with one of the most famous solutions to the “demarcation problem” of establishing what does and doesn’t count as science.

Falsifiability, rent control, and summarization

You would be hard-pressed to find a policy economists dislike more than rent control. Here’s Assar Lindbeck, writing in The political economy of the New Left: An outsider’s perspective:

In many cases rent control appears to be the most efficient technique presently known to destroy a city—except for bombing.

This is also an issue where economists sharply disagree with the public. Americans overwhelmingly support capping the amount a landlord can raise rent, with about 82% expressing support for the idea in a survey. In a survey by the Kent Clark Center, 74% of the surveyed economists disagreed that such a move would make middle-income Americans “substantially better off”, with 16% remaining uncertain and 2% agreeing.1

The views of economists are rarely diverse once you look closely. The lone economist who agreed in the rent control survey was Hilary Hoynes. One of her college presentations, available online, says that rent control causes a shortage of housing. It seems likely that she, like some economists who responded with an accompanying explanation of their position, wondered if specifically middle-income Americans would benefit from the distributional impact.2

This section is about falsifiability, not rent control—I’ve merely chosen this policy to use as an example case. Karl Popper was a famous “philosopher of science”, meaning a philosopher who studies how science is used to understand the world. He used the idea of falsifiability as a means of solving the “demarcation problem”, mentioned a moment ago. It might be helpful to stop and try to think of examples of pseudoscience and how they’re immune to falsification.

I’ll give you my own examples. You could, in principle, show that gravity is not a universal law by finding a large astral body that does not appear to have any. But suppose you’re given a crystal with “healing properties.” If you like science, you might come up with an experiment to see if it works, randomly keeping it with you some days and not others, and recording the results. If you’re especially good at science, you’ll find a placebo crystal to use on some days, and let a friend give you one or the other without telling you which is which. You’d probably find the real crystal does nothing. If you confronted the crystal salesman, they might tell you that it’s meant to improve your “spiritual energy”, rather than improve your physical health. That’s what makes its healing properties pseudoscientific. If you want to do science, you need your ideas to “take risks”, exposing themselves to falsification. If your outcomes are not observable, your ideas are not scientific.3

Popper took this idea a bit further by arguing that scientific theories can almost never be confirmed by evidence, only disproven. “All ravens are black” is a classic example where observing a white raven would definitely prove you wrong. But some philosophers still disagree about whether observing a black raven should make you more confident that all ravens are black, since you could always see a white raven someday.

Let’s return to the example of rent control. Supposing you think rent control increases access to housing, is there some way for you to falsify what economists say about rent control? Absolutely: we saw in the previous post that economists have the whole toolbox of econometric methods to test the effects of rent control. A study of rent control in New Jersey found that rent control policies there had a minimal impact on “rents, number of rooms, quality of units, and new rental construction”. This was cited in an article arguing that economists are wrong to hate rent control. So it seems that economics is falsifiable, and we’ve falsified the idea that rent control hurts accessibility.

But the economists aren’t wrong. The first issue is that the position economists hold is not really that rent control is bad per se, but that binding rent control is bad, i.e., rent control policies implemented where landlords would otherwise have chosen to charge higher rents. This would occur if, for example, rent control required 50% lower rents and nothing about supply or demand changed to accommodate such lower rents. (If the government required lower rents at the same time that landlords were going to cut rents anyway, that wouldn’t show that rent control works.) The lack of binding rent control policies in New Jersey is what the authors identified as an explanation for the unexpected behavior. The authors had specifically been looking at rent controls that limited the size of rent increases, and noted that these controls appeared moderate and “toothless”. So it seems that the article I mentioned, which argues in favor of rent control, was dishonest about the work it was citing.

But this feels similar to the effect of the crystal on your health, because you could just say “it must not have been binding” and move the goal posts every time someone finds that rent control didn’t hurt housing supply. This leads into a more general point to be made about any statement made by economists: “it depends” should usually be attached. The effects of a policy change will depend greatly on its magnitude. Economists would not be too concerned about a federal law capping the growth of rents at 200% per year, since landlords would very rarely raise rents that quickly. They are far more worried about other programs that appear to run the risk of recreating the failures of the most restrictive policies they have observed.

If you would like to know where to find those observations, here’s a summary of evidence on rent control from Richard Arnott, writing in 1997:

Nevertheless, the cumulative evidence—both quantitative and qualitative—strongly supports the predictions of the textbook model in virtually all respects. The decay and shrinkage of the rental housing markets in Britain and Israel caused by long-term rent control are persuasively documented in Coleman (1988) and Werczberger (1988), respectively; Friedrich v. Hayek (Fraser Institute, 1975) provides evidence of the harmful effects of hard rent controls in interwar Vienna, including their adverse effects on labour mobility; and Bertrand de Jouvenel (Fraser Institute, 1975) and Milton Friedman and George Stigler (Fraser Institute, 1975) argue strongly that the retention of controls immediately after World War II adversely affected the Paris and U.S. housing markets, respectively.

New York and San Francisco provide additional examples of cases where rent control failed, if you need more. Note that rent control does reduce rents for the people living in a city, but economists are usually benevolent enough to argue that people not living in a city shouldn’t be excluded from the large benefits of migrating to it. You can make housing more affordable for current residents using rent control, but if you did so everywhere, cities would struggle to grow by building more units. That would constrain upward mobility for some of the least privileged people in society.

In general, the statements economists make have fairly well-established exceptions that economists expect to observe from time to time. So while they might at times appear immune to falsification, that’s only because statements about economics are often simplified. “Rent control causes a shortage of housing” is not really what economists believe. Economists believe that binding rent control creates a shortage of housing in a competitive market, assuming no simultaneous changes in supply or demand to accommodate the forced decrease in rents. The annoying part of this specificity is that it means you have to understand economics before you challenge it. The nice part is that, eventually, there are clear ways you might falsify the ideas of economists.

You might identify a case where most landlords suddenly started charging at least 20% less than they were beforehand because of a broad rent control policy, and where the number of new units built increased. An economist might still be able to challenge your evidence by pointing to the elimination of regulations that previously made it expensive to build and maintain housing. You would have to make sure that both supply and demand remained constant to pose an effective challenge, but once you had done this, similar results were replicated elsewhere, and some reasonable theory had been created to explain the results, you would change their minds (and probably win the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences).

You should take this level of complexity as a good thing that allows economists to explain more, not a bad thing that makes it harder to challenge their ideas. If I, or any real economist, were shown a housing market where supply is only provided by a state-protected private monopolist, we would probably predict that a rent control policy forcing rents down by 10% would not create a shortage. (The reasoning behind this will only be clear if you study the standard model of a monopolist, and would draw our focus in the wrong direction.) These additional predictive capabilities are rarely needed because most markets we observe seem fairly competitive.

It may be important that I provide a response to a common description of the problem of high rents: that landlords charge high rents because they are greedy, and refusing to impose rent control simply benefits them at the expense of renters. Rent control is a form of class warfare to many of its advocates. This is true, but it misses the point. As I described, economists are more concerned about the consequences of rent control for people who don’t live in an area, not the people who already do. Rent controls are very effective at lowering prices for people who already live somewhere, and very effective at keeping out people who might benefit from huge wage increases just by moving to a city.4 Economists don’t want to tell a simple story of class warfare. They advocate fiercely against rent controls because of the indirect “second-order” consequences of it for non-residents, which they have studied extensively.

Another issue you might be noticing is that it’s not clear how the evidence should be summarized, because there are so many different cases where rent control has been implemented in just as many different ways. If we want to be able to falsify ideas in economics, we need to be able to summarize attempts at falsification. And assuming there are negative effects, we’d like to be able to estimate and quantify how strong they are, and these estimates will inevitably vary.

The truth is that there is no single way to do this, but there are ways that you should find very convincing. But you shouldn’t take that to mean that anything goes, or that economics is pseudoscientific.

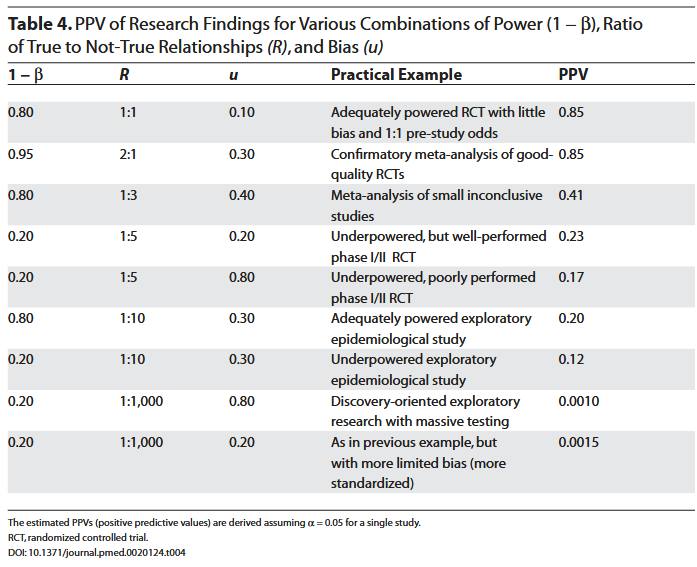

Problems with summarization are held in common with other sciences like medicine. You can find, for example, a study showing that elderly patients who received the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine were 22.5% more likely to develop Alzheimer’s. Vaccine skeptics were happy to post this study on Reddit, which is how I found it. But even if these results are accurate, you can also find a review of evidence on the vaccine’s effectiveness that says it reduces the rate at which people are hospitalized for the disease by 97.2%.

Now, I am but a lowly economics graduate and not a health professional. But the only real problem with believing the Alzheimer’s study, by all that I can tell, is the interpretation. The Alzheimer’s study looked at Koreans over 65, and Alzheimer’s occurs in just 10.25% of them, meaning they found the vaccine raises the rate to something like 12.56%. The difference is about 2 percentage points, meaning the study found a one in fifty chance that you get Alzheimer’s from the vaccine, assuming the correlation represents a causal effect of the vaccine. This is interesting, but hardly a good reason not to get the jab. The issue here is one example of the base rate fallacy, perhaps better called base rate neglect, wherein the general rate at which something occurs (in this case, the general rate of Alzheimer’s among those over 65 in Korea) is ignored to come to an incorrect conclusion (“the COVID-19 vaccine creates a significant risk of memory problems”).

Through the lens of falsification, there are some problems in economics. When Karl Popper wrote about falsification, he judged that a good scientist would actively try to expose their explanations to tests that might falsify them. I’m afraid I can’t say that economists are always like this, except as a collective, and that makes progress very slow. When David Card and Alan Krueger challenged the consensus on the effect of a minimum wage hike on employment with their study of a minimum wage hike in New Jersey, they received a lot of scorn from other economists. Some treated the idea that a minimum wage might raise employment, as they found in their study, as completely insane. Here is a fun quote from Nobel laureate James Buchanan, writing in the Wall Street Journal after Card and Krueger’s study was published:

The inverse relationship between quantity demanded and price [i.e. the idea that raising prices reduces the quantity people want to buy, all else equal] is the core proposition in economic science, which embodies the presupposition that human choice behavior is sufficiently rational to allow predictions to be made. Just as no physicist would claim that ‘water runs uphill,’ no self-respecting economist would claim that increases in the minimum wage increase employment. Such a claim, if seriously advanced, becomes equivalent to a denial that there is even minimal scientific content in economics, and that, in consequence, economists can do nothing but write as advocates for ideological interests. Fortunately, only a handful of economists are willing to throw over the teaching of two centuries; we have not yet become a bevy of camp-following whores.

It seems Buchanan wasn’t interested in evidence showing he was wrong, even only a little wrong. This doesn’t look like the kind of attitude Popper would describe as scientific. He does make a good point in saying that economists should not be “advocates for ideological interests”, but this only distracts from the question of whether the work Card and Krueger did was good.

Today, economists generally believe that the effect of a minimum wage hike on employment is indeed negative, but small, unlike past generations who believed the effect was fairly sizeable.5 They generally prefer other policies, like wage subsidies, as a way to improve the livelihoods of workers. I don’t think that this problem is unique to the field of economics, which is why it’s still worthwhile to engage with it if you care about science in general. But it’s certainly more common. I’ll give closer attention to the ability of the field to change in response to new evidence later. First, let’s take a closer look at summarization.

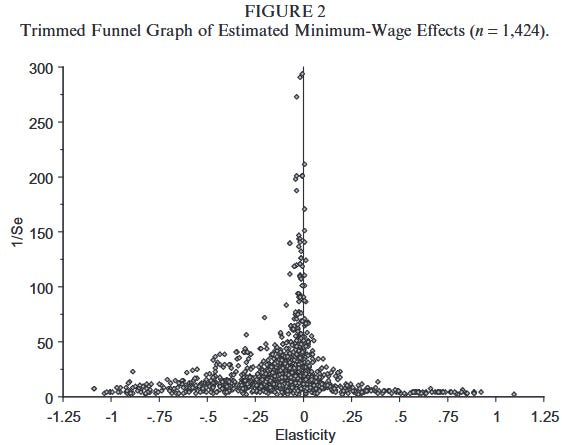

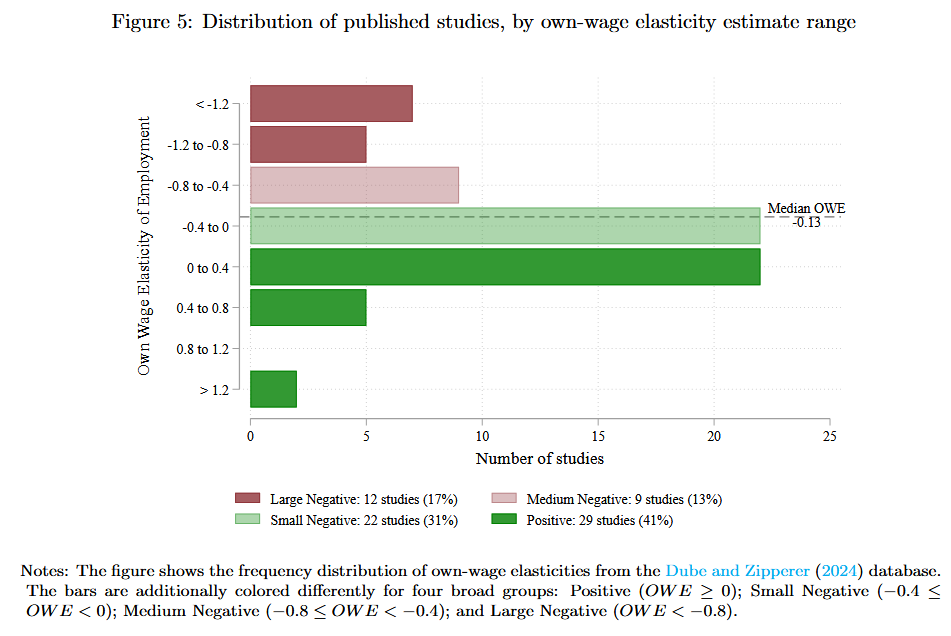

There are some problems with relying on surveys of economists to understand the world, as described by Scott Alexander. For one, the phrasing of survey questions could cause different results. Worse, the panel of economists you survey could matter a lot. 500 economists signed a letter warning against raising the federal minimum wage in 2009. Another 600 economists signed a letter five years later saying it would be a good idea.6 Here’s a plot of minimum wage employment elasticities found in various studies. (An elasticity refers to the percentage change in the quantity of something divided by the percentage change in the price. Here, the quantity is employment. You can just think of it as the effect of the minimum wage on employment, meaning values further to the left in the plot indicate that the minimum wage hurts employment.)7

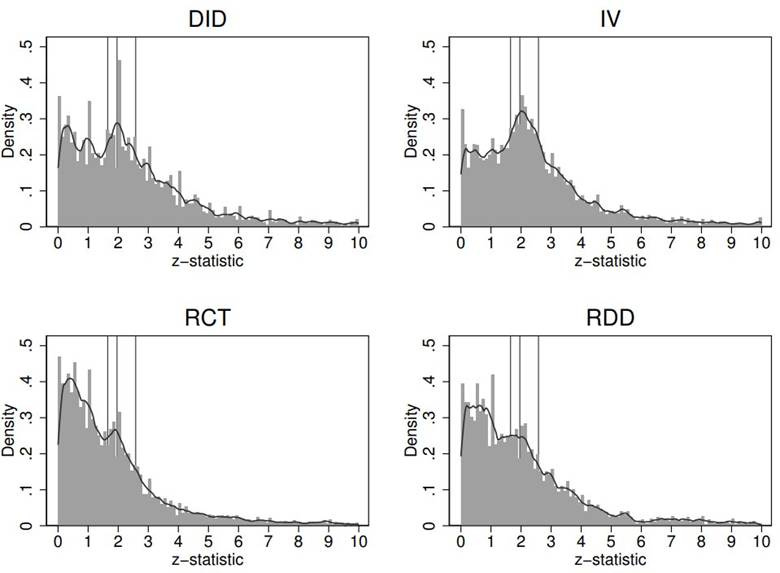

“1/Se” means one divided by the standard error of the effect, explained in the previous post. If you didn’t read it or otherwise had a hard time with it, just think of the vertical axis as describing how confident you should be that the observed effect is real. This plot tells you that the typical effect is negative, but near zero.8 It was designed to reveal substantial publication bias in economics: while we expect to be measuring a real elasticity near zero and for random errors to occur, the errors are clearly not random and create a bulk of studies on the negative side. That suggests that studies are more likely to be published if they show a negative effect, or perhaps are often designed to show one where none exists. After adjusting for this bias, the effect appears to be slightly positive.

The evidence here is bewildering, and the ambiguity might be upsetting to you, but it doesn’t preclude economics from having a consensus. There are statements that we know are almost certainly false, based on available evidence:

The minimum wage generally reduces employment by “a lot”, i.e., the employment elasticity is typically less than -1.

The minimum wage generally raises employment by a lot.

The minimum wage always reduces employment.

We would prefer to have stronger beliefs about the minimum wage, but this is still a very useful consensus. It tells us that the minimum wage is not inarguably good or bad and can be a useful tool for raising wages, even if it can be expected to often reduce employment.

In general, if you wish to know what the consensus is among economists, start with the Kent Clark Center’s surveys. If you would like to be even more sure about it, look for other surveys and literature reviews. Do not rely wholly on credentials except as a last resort (e.g., “this economics PhD holder joined us for an interview and says x is a good policy”), instead, make sure that the speaker is themselves relying on some review of available evidence. It’s also good to check if they’re deviating substantially from the evidence (even some Nobel winners catch “Nobel disease” and adopt nutty ideas). If you want to understand how that evidence identifies causal effects, return to the previous post.

The ability to falsify an idea, as a way to decide what is and is not science, has its issues. One issue is that some explanations we might want to falsify only tell you that something is very unlikely to happen, rather than telling you that it won’t happen at all. When playing cards with my family, I often shuffle the cards and claim that I thoroughly shuffled them. When they dislike the cards that they’re dealt and tell me that I didn’t shuffle properly, I tell them that any combination is possible with a properly shuffled deck. So it seems that my claim that I shuffled properly is unfalsifiable and pseudoscientific. This is obviously wrong, so we should create an exception.

Popper responded to this issue by saying that some ideas are falsifiable “in practice”, even if not literally falsifiable. Drawing three kings together is unlikely with a properly shuffled deck, but not impossible. Before handing out the cards, I should simply say that if out of the four cards everyone is dealt, everyone gets three matching cards, I will have failed to shuffle properly. This bar is very low, but it demonstrates the idea well enough. It would rarely cause problems for someone who shuffled properly.

Similarly, economists often consider certain outcomes to be very unlikely but not impossible. Right now, economists would say that it is very unlikely that the US experiences an economic boom with more than 3% real GDP growth each year for the next four years. Booms are rare in general, and the president has introduced a supply shock by raising tariffs. They would not necessarily be wrong if a boom happened anyway.

We should take a moment to explain exactly how the ideas of economists can be falsified when they make generalizations that they don’t guarantee to be true. Without making this clear, economics will look not just pseudoscientific, but meaningless. We won’t know how to interpret and understand the things economists and other social scientists are inclined to say with phrases like “it seems”.

In the previous part, I wrote the following:

The methods used by actual statisticians to forecast elections are more advanced than what I have presented here, but are fundamentally the same. They rely on polling data and other variables to forecast elections with random simulations. As you’ll see in the next part, which elaborates on exactly how these percentages work, they tend to be very good at their jobs.

Now we’re going to see what I was referring to when I said “how these percentages work”.

Confidence levels

In 2016, FiveThirtyEight, which primarily depended on the work of statistician Nate Silver, claimed that Hillary Clinton had a 70% chance of being elected President of the United States. Many today are happy to declare that Silver was wrong about this, and unfortunately for them, I will now be providing a very good explanation for why they’re wrong. None of them understand what Silver meant.

Most people agree that they aren’t always right about everything. If I wanted to try predicting the weather, I could say “I’m 71% confident it won’t rain in London tomorrow”, since that’s roughly the share of days in London where it doesn’t rain during a year.9 This leads us to a very explicit definition of confidence levels using the definition of the limit of a sequence, which is important in mathematics. You might be a little overwhelmed for a moment here. If you don’t like math, skip this part. It’s only been included because I like being formal and enjoy writing about math.

When I say I’m 70% confident it won’t rain in London tomorrow, I mean something like this:

∀ ε > 0, ∃ N ∈ ℕ such that ∀ n > N, | cn - 70%| < ε

where cn is the value of a time-ordered sequence of averages made by averaging the time-ordered list of claims I’ve made with 70% confidence and evaluating them as true (1) or false (0), and my statement about London is included in the construction of this sequence.

That’s very precise and might seem very nice if you know what all those symbols mean, but you’re probably feeling bewildered. As you’ll see in a moment, essentially what I’m claiming here is that in the long run, statements I make with 70% confidence are right 70% of the time.

Let’s begin by thinking about sequences. A sequence is an ordered list of numbers that have been enumerated. For example, {0, 5, 10, 15} is a sequence. We can call the first member “s1”, the second “s2”, and so on. We can refer to an arbitrary member of the sequence with “sn”, like we did in the funny statement with the symbols. This allows us to talk about members of the sequence with characteristics like “n > 1”, meaning they are past the first member.

The first symbol in that statement, an upside-down A, means “for all”, so I’m saying “for all ε > 0”. ε is a small number someone can pick to try to show I’m wrong. You could call it an error—let’s say it’s 5%. Then there’s a backwards E, which means “there exists”, followed by our last two weird symbols, “∈ ℕ”, which means “inside the set of natural numbers.” The natural numbers are the numbers you use for counting things. It includes 1, 2, 3, and so on. We use them to give names to members of sequences like the one used here.

Let’s bring all of that together. The first part of the funny symbol statement is “No matter how small an error you pick, there’s some N in the natural numbers [a position in our sequence of averages saying how often I’ve been right] such that…”

Let’s continue to the rest of the statement, “∀ n > N, | cn - 70%| < ε”. This is saying “for all n greater than some N we said we know exists, the difference between something called cn and 70% is less than the chosen error.”

What’s the sequence I described? We need to construct a simpler sequence before we can get it, which describes whether I was right (denoted with a 1) or wrong (denoted with a 0). If the only claim I ever make with 70% confidence is that it won’t rain in London tomorrow, the sequence of values saying whether I was right or wrong might look like this: {0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1}. The first 0 is there because it actually did rain, and I was wrong. Then there’s a 1 because it didn’t rain, meaning I was right, and so on.

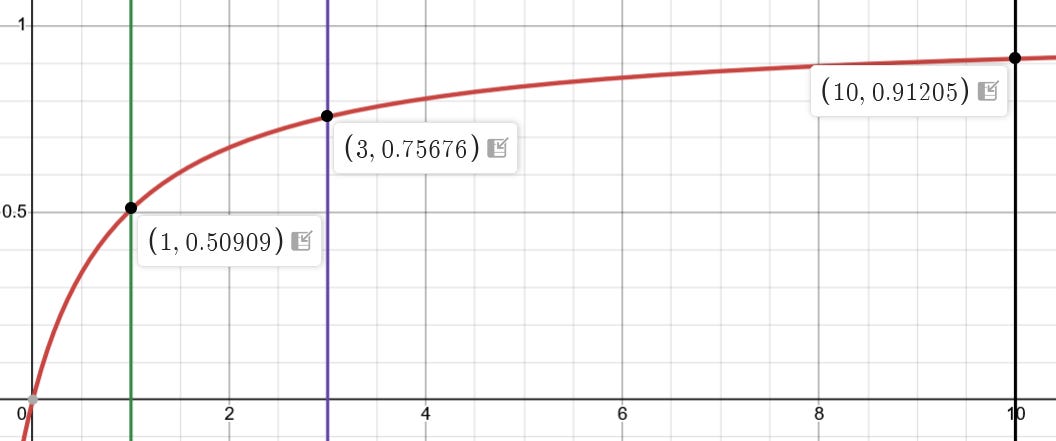

The sequence of values cn is the sequence of averages of all preceding 1s and 0s: {0, 0.5, 0.66, 0.5, 0.6, 0.5, 0.57, 0.625, 0.66}. Think of this as the sequence that tells you how often I’ve been right in the past. Notice that the first number in this sequence is 0 because the first number in the original sequence is 0, and the average of a single number is that number itself.

For the first 9 predictions, the average of the values is about 0.66. This is pretty close to 0.7, which is what I’m saying the average will be in the long run. If you chose a 5% error, like I described, then I can say, “Look, if you take the first N = 9 numbers in the sequence, the average is 0.66. Its difference with 0.7 is less than 0.05. In other words, | cn - 70%| < ε. The same is true for every prediction after it (because there are no more predictions), so I was right.” That looks like what the statement was saying: I can find a point in the sequence at which the difference between cn and 70% is less than the small number you chose, and every number after that point is just as close.

Let’s try to put it all together. I’m saying that for all little errors you can think of, if you track my predictions long enough (pick a sufficiently large N), then after that point, for every value in the sequence that tells you how often I’ve been right in the past (cn), the difference between cn and 70% will be less than the small number you picked. In other words, I can become as accurate, on average, as anyone would like, so long as you wait long enough.

This is not really what statistical forecasters mean, because they can’t satisfy requirements this strict. I might have some bad luck and, after becoming as accurate as you requested, become less accurate. A weaker and more realistic form of this same idea can be stated as follows. This is what you should apply to forecasts in general.

When something is predicted with x% confidence, the following should be true:

∃ N ∈ ℕ, N < 1000, such that ∀ n > N, | cn - x%| < 10

This statement tells you that at some point, with fewer than 1000 predictions, the difference between how often someone has been correct and how often they claimed they would be correct is less than ten percentage points, and this remains true forever. The choice of 1000 predictions and a difference of less than 10 percentage points is arbitrary but suitable for most purposes. I would expect statisticians to often be even more accurate, meaning we can write something like “| cn - x%| < 5” instead.

Even after all this explaining, you might still struggle to understand. The most essential lesson here, however, is that if somebody tells you they’re 70% confident something will happen, what they’re saying is very different from claiming something will happen. They’re telling you they could be wrong, and how often they expect to be wrong about things they assign the same confidence level to. Nate Silver and the other people working at FiveThirtyEight in 2016 were saying there was a 30% chance that Trump would win instead of Hillary Clinton. In that case, Trump did win, and they allowed for this possibility. Communicating this essential idea has proven very difficult.

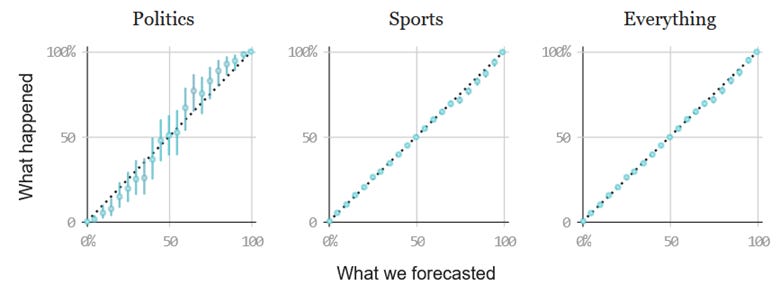

This might seem unfair. Why let experts escape from being wrong by just saying they’ll be wrong a certain percentage of the time? You would certainly prefer someone who is always right, but nobody like that exists. This way of thinking creates more accountability, not less. It formalizes the common idea that nobody is always right, and allows us to verify that someone makes accurate predictions. Below, you can see how often the statisticians at FiveThirtyEight (mostly just Nate Silver, to my knowledge) were right about different things.

To understand these charts, focus on the politics chart, and pick a number on the horizontal axis on the bottom. That’s the confidence level they gave for the outcome of many different elections. Now look at the dot above that confidence level, and check its position on the vertical axis. It should be very similar, meaning those election outcomes they forecasted happened as often as they said they would. Election outcomes that they claimed had a 50% chance of happening happened about 50% of the time—just look at that dot in the center of the graph. This might look confusing at first, but it’s really a wonderful form of humility and transparency. Anyone is free to record FiveThirtyEight’s predictions and make a chart just like this, so I wouldn’t expect it to be a fabrication.

Scientists outside of political forecasting organizations don’t have a habit of talking like this, because it’s potentially life-saving to say “Vaccines save lives” rather than “I am 95% confident vaccines won’t give your child autism” or anything to that effect. Skeptical attitudes can, in some cases, give the public a permission slip to think they know better than the experts and hurt themselves. Knowing that their work is highly specialized and difficult to understand, scientists prefer to communicate with authority in the same way a parent communicates with their child. This is demeaning, but likely saves lives. You might have an easier time sympathizing with this view if you encounter someone who is confidently incorrect about something you know a lot about.

Academic papers often include an analogous measure called confidence intervals. When trying to identify something with a random sample, scientists often report an interval of values and a confidence level. If a paper says something like “The 95% confidence interval for the effect of one dosage of the drug on a user’s weight in pounds is [-10, -1]”, they mean that a random sample with a confidence interval of this size will contain the true effect of the drug 95% of the time. In other words, they are 95% confident they have captured the real effect of the drug within their confidence interval, which is vulnerable to random chance to some degree.10

Knowing all of this, it should be clear that there is some good sense in uncertain predictions about the future, and that you should expect these from serious thinkers in science, including economists. That economists have been wrong about some things in the past is not a very effective indictment of their behavior.

Troublingly, few keep a quantitative track record like the one above, so we are often forced to judge based on the few examples we have seen from a particular expert. Depending on the sources you rely on, those examples may have been selected specifically to make them look bad—a comprehensive track record is often what we really need, but can rarely get.

Think about how misled you would have been if someone had only told you about Silver’s prediction in 2016 and none of the others. For an example of an economist being treated this way, consider this post on X, showing Paul Krugman’s prediction that the internet will have a minimal impact on the economy. In a certain sense, he was wrong. The internet permeates the whole economy and daily life for billions of people. It would have been better for Krugman to show some humility and say his prediction was “almost certain” or “likely”.

The question of whether internet access and growth are causally related is a bit more controversial, and I would have to dedicate substantial time to it to produce a summary. Some estimates suggest it does, but these effects don’t appear substantial. I personally suspect Krugman was wrong, but not very wrong. His wording would have benefited from additional specificity about the degree and type of impact. Albert Einstein, likewise, made a terrible mistake by thinking the universe was static rather than expanding. Despite this, we use his ideas every time we rely on GPS for navigation. Being wrong sometimes is not a crime.

Krugman may have been wrong about the internet, but he was right about other things. He warned that the fiscal stimulus passed into law during the Obama administration, the ARRA, would be an insufficient response to the Great Recession. As he expected, the United States experienced sluggish growth after the crisis compared to the relatively stable rate of growth that preceded it. European countries that engaged in austerity fared even worse.

In general, I would avoid extrapolating too much from the mistakes of economists and other experts. It’s better to learn more about them first.

Before proceeding, I should mention that it’s often not clear how a percentage interpretation can be given to statements about the economy. Krugman’s warning about ARRA included language like “could”:

But he suggested that inadequate economic policies in the U.S. today could lead to something akin to the so-called “lost decade” of economic growth in Japan during the 1990s and early 2000s. In fact, noting that Japan’s economy is falling precipitously today, Krugman said Japan could now be headed for “lost decades.”

“Could” includes things with only a 1% chance of happening, but that’s clearly not what he meant. Similar ambiguities could arise in other cases. The important thing is that predictions tend to occur more often as confidence unambiguously rises.

Unfortunately, surveys of economists have shown that they tend to be overconfident in their predictions of things like unemployment and inflation. I hope others will learn from these mistakes. But economists are more focused on making good policy recommendations than forecasting the economy. It would be a terrible error to judge them based on this, like judging the expertise of public health experts based on their ability to predict hurricanes. I expect economists to show better judgment in their own realm, especially in extreme cases where the literature points overwhelmingly against a policy, like with rent control. But I’m not aware of any study looking at this question retrospectively, i.e., judging whether the policy recommendations of economists have generally had their expected effects. This would be a good area for future study.

Laws in Economics

It’s come to my attention that, at least among some internet users, sciences require universal laws. I don’t think this is right―we’ve just seen that strong generalizations are meaningful even if they’re only generalizations. Regardless, we should spend some time examining whether or to what degree there are laws in economics.

The most obvious candidate for a law in economics is the idea that people make rational choices: faced with multiple options, people pick the one where the marginal benefit most exceeds the marginal cost. You wouldn’t buy an apple if you don’t like apples, and you wouldn’t work at Arby’s if you think the wage doesn’t compensate you for the working conditions. People generally don’t consider sunk costs and do consider opportunity costs. If, for example, you saw that you would benefit from going to a public university, you would still rather go to Harvard, since attending the public school would mean forgoing the benefits of Harvard.

But I would only describe this as a generalization that holds most of the time, and any economist with a bit of sense would agree. There are definitely exceptions, and these are well-documented in Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow. For example, a rational actor should be just as likely to choose a surgery with a 90% survival rate as a surgery with a 10% mortality rate—these two numbers mean the same thing. But framing it as a 90% survival rate makes people more likely to choose it.

The exceptions don’t worry me. In the first place, these exceptions are ultimately evidence for the point I’m making: people are generally rational. Sometimes, people use quick thinking and apply heuristics that lead to irrational choices. Kahneman describes this as a problem caused by “System 1”. But these decisions implicitly endorse heuristics that generally lead to rational choices. In other words, people clearly choose to behave on the basis of rules that are usually rational.

The framing effect example suggests that people aim for high survival rates more than low mortality rates, but most of the time, doing this will still lead to the same, rational choice. If a disease kills 1% of the time, framing the surgery that treats it as having a 90% survival rate will do little to encourage someone to get it. They’re going to notice the irrationality of getting the surgery regardless. There are certain cases where this framing effect might matter, but like setting the price at $5.99 instead of $6, the effect is small.

With all the exceptions we can find, behavior is still usually rational, and that’s what counts. During the Alaskan oil boom, oil companies raised wages, attracting more workers to Alaska. That shows rational behavior in both parties. Every natural experiment featured in the previous part likewise showed, in some way, rational behavior. Firms were shown to prefer workers with greater signs of conscientiousness in the example describing the GPA-income connection. I don’t think the models of rational behavior involving utility functions are literally true to reality, but they aren’t meant to be, and instead provide a simple description of how people weigh costs and benefits in practice.

John T. Roberts (a philosopher of science, not the Supreme Court justice) has an excellent exploration of the more general question of whether the social sciences have laws, and if I could reasonably ask you to, I would tell you to read it instead of reading this. But that would take a while, so I’ll try to summarize his points before commenting.

Roberts believes the social sciences, including economics, do not have laws. In the sense he means this, I actually agree with him. The definition of law he uses is reasonable, but also very strict: he wrote that physicists probably haven’t discovered any laws yet, but “maybe someday” will, and that we don’t really know if physics has any laws. But he does say that the successful theories in physics posit some laws. The successful theories in the social sciences don’t, but they do suggest generalities, like the ones I’ve described.

On the question of whether the laws of supply and demand are really laws, he agrees with me that they’re only regularities, and there are plenty of exceptions. He uses price controls as an example of an exception: if demand rises without a commensurate increase in supply, prices would normally rise, but they can’t do that with a binding price control.

I don’t think this is a good example. Price controls are obvious and allow us to modify our predictions easily. The real trouble comes from other examples he gives, like the possibility that “humanitarian feelings on the part of many vendors motivate them not to raise prices on goods.” Under some formulations of rational choice theory, this would cause it to fail, but I would always include altruistic benefits among those considered by businesses when making choices. In any case, I’m not aware of any case of this actually happening.

Arguing that the laws of supply and demand can only be hedged laws, Roberts appeals to ignorance: if there are exceptions, “Who knows how many others there may be?” I’m inclined to agree. There might be laws in physics that hold everywhere, but the world is just too complicated for us to strictly identify every possible exception to the laws of supply and demand. Even an unexpected meteor strike can interfere with the outcomes of a market. The problems he describes are problems for all sciences, not just the social sciences, but they seem to cause more trouble for economics than physics.

Roberts spends some time arguing that because (i) social laws must be hedged, and (ii) there are no hedged laws, there are thus no social laws (i.e., laws in the social sciences). In short, refusing to hedge a social law by including exceptions means opening the law up to rapid falsification from some exception, because social systems are so complex. That shows, or at least suggests, that (i) is true. And if you do have a hedged law and try to include every exception possible, you inevitably don’t include all of them, showing (ii) is true. So there are no social laws.

He finishes by arguing that social science “need not posit laws”. Here’s the conclusion, which provides a good summary:

Prediction and explanation require reliable sources of information about the world, in the form of strict or statistical regularities. Laws of nature are regularities that have certain features: they are global or universal, and robust, in the sense that they do not depend on contingent details of particular systems of objects, and they would not be upset by changes in the actual circumstances that are physically possible. In order to have explanatory and predictive value, though, a regularity (strict or statistical) need not have these special features. Hence, not only does social science have no laws; it needs no laws.11

The book this is taken from, Contemporary Debates in Philosophy of Science, includes a pro and a con section for every part of the book, each talking about a question. Roberts’ argument is followed by “There are Laws in the Social Sciences” by Harold Kincaid. That would definitely help my case, but Roberts’ view comes closer to mine.

You might take the presence of both of these sections as an endorsement of the idea that all truth is relative, but I think you should learn to see past that and piece together the points held in common by different experts. Roberts and Kincaid alike would agree that the social sciences have documented regularities we can rely on to hold in the future. “Economics is inconsistent and tells you nothing about the world” is just an uninformed statement, which is why neither Roberts nor Kincaid believes it.

We should finish by looking closer at why Roberts thinks laws are unnecessary for science. I’ve already described how he believes physicists have yet to uncover any laws of physics, but this sounds ridiculous. Isn’t Newton’s second law of motion (F = MA, essentially) a law of physics? No, he says, because we’ve found exceptions. He didn’t name these exceptions to Newton’s second law, but I hunted one down for you: objects change in mass as they approach the speed of light. We know this from general relativity. So, a simple law about mass implied by Newton’s second law, M = F/A, is not true if A is sufficiently large. Apparently, similar problems arise even with general relativity and quantum mechanics, since they’re incompatible with each other.

My hope is that Roberts’ summary of the field of physics from 2004 is still accurate. After all, if such a profound development as finding the first true law of physics occurred, I’d expect to have heard about it. But the essential components of the argument should still hold regardless.

To summarize, it seems that there could be laws in physics, but not in economics. This is fine because we don’t even have laws of physics yet, so our current knowledge of physics would be tossed out as “unscientific” if we required the presence of laws. So either the regularities described by economics are scientific, or we don’t have science at all. I feel bad re-hashing Roberts’ argument so much, but it’s very strong.

Responsiveness to new evidence

Physicists once hypothesized the existence of “luminiferous ether”, something that filled the space between planets and permeated the air around us, allowing light to travel through a vacuum despite being a wave. In principle, this idea could be falsified, and it was: the Michelson–Morley experiment showed that there is no ether. The Earth orbits the Sun, so if the ether existed and filled the space around both bodies, there should be an “ether wind” caused by the movement of the Earth around the Sun. It couldn’t be stationary relative to the Earth at all times. Michelson and Morley attempted to measure the ether wind by measuring the speed of light in perpendicular directions, but found results consistent with no movement at all, leading physicists to the conclusion that the ether doesn’t exist and light propagates through empty space. Another experiment, the double-slit experiment, showed that light is both a particle and a wave.

It’s tiring to hear that the sciences should all seek to imitate physics. Sometimes, it’s just not possible. But responsiveness to new evidence is one of the most important features of any science. Otherwise, like Buchanan had said before, economists might be a “bevy of camp-following whores.”

Looking from the outside in, you might suspect that economists have believed the same things for a long time. This is plain wrong. Let’s begin with the example of Say’s Law, named after Jean-Baptiste Say. The law essentially states that supply creates its own demand. By creating a valuable product, you create new demand for product(s) of comparable value to what you’ve made. This happens because your product is quickly sold, giving you and your workers money to buy other products with. Because of this, a “general glut” of goods should never occur.

With the onset of the Great Depression, the unemployment rate rose to a peak of 25%, leaving large amounts of labor unused. This caused products to remain unsold, in many cases, in what was apparently a general glut. The unemployed just didn’t have the money to buy those goods. Say’s law implied that what economists were observing couldn’t occur, in the same way that the ether implied that what Michelson and Morley observed couldn’t occur, falsifying it.

Economists began to change their minds. New ideas were provided by John Maynard Keynes in his General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. This was later summarized mathematically by John Hicks and Alvin Hansen as the IS-LM model. That would take time to explain, but for now, it’s good enough to tell you the key idea: supply doesn’t create its own demand if there isn’t enough money to go around. The Federal Reserve, which controls the money supply in the United States, played a big role in causing the Great Depression by lending to banks at high interest rates (in other words, by making money expensive and scarce). The Fed also played a big role in stopping a second depression in 2008 by expanding the money supply, though the combined response of the Fed and Congress was insufficient.12

Here’s economist John Kenneth Galbraith describing the change:

Until Keynes, Say’s Law had ruled in economics for more than a century. And the rule was no casual thing; to a remarkable degree acceptance of Say’s Law was the test by which reputable economists were distinguished from the crackpots. Until late in the ’30s no candidate for a Ph.D. at a major American university who spoke seriously about a shortage of purchasing power as a cause of recession could be passed. He saw only the surface of things, was unworthy of the company of scholars. Say’s Law stands as the most distinguished example of the stability of economic ideas, including when they are wrong.

Here, Galbraith seems to be disagreeing with me. I think he may have been right to say that ideas in economics are stable even when wrong, but this doesn’t seem to be exceptional about economics. Physicists believed in the ether for centuries, despite it being completely unobservable and non-existent. I don’t blame physicists for this failure because the work of physicists, like the work of economists, is difficult. Interestingly, economists give far more respect to the field of physics than they get in return. Supply really doesn’t create its own demand.

Some old ideas in economics remain pervasive today despite their rejection by economists or their weakening. The efficient-market hypothesis (EMH) is one example, stating that asset prices reflect all available information. This means, for example, that if you see a headline from yesterday about how Apple had an unusually good financial quarter, buying stock in Apple will do you no good: the price will have already risen to compensate for the greater expected profits.

The EMH received a great deal of support from economists like Eugene Fama, who noticed that stock markets follow an unpredictable random walk in the short run, consistent with the EMH. This is still a good way to think about financial markets, and you should never expect to easily beat the market, or even to beat it with a great deal of effort. But the EMH has been weakened by empirical evidence. S. Francis Nicholson, for example, noticed that financial analysts generally believed that stocks with high price-to-earnings ratios would perform better, but the opposite is true in practice. I would assume that this caveat has become so well-known that you can no longer make money by buying stock in companies with low price-to-earnings ratios, but I may be wrong.

There are plenty of people who want the field of economics to change faster and accept their ideas, and I can’t address all of them at once. Let’s focus on just one direct challenge to the field of economics: that globalization has failed to produce the results economists promised and has instead brought misery and decline. This is not an example of an area where the field needs to change, but instead an example of how difficult it is for the field to communicate to outsiders.

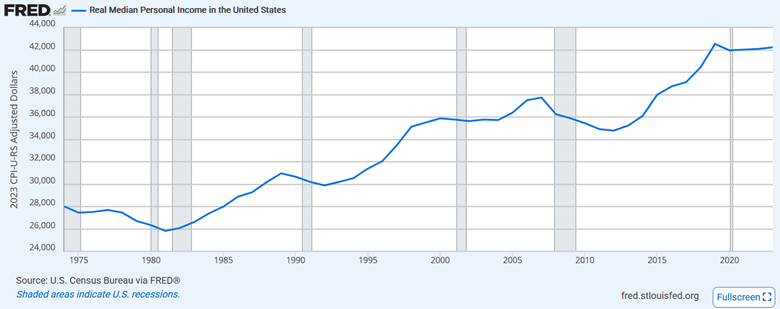

Anti-globalization rhetoric often includes a broader form of rhetoric I like to call real income denialism. At any given point in time in American history, you can rank Americans by their income and take the income of the person in the middle to get the “median” income. The average price level tends to rise over time, so we need to adjust for purchasing power with an index of the price level to learn about how incomes have changed over time. We call incomes that have been adjusted for inflation “real” incomes. To give a mathematical example, if incomes grew by 40% over a period while the price level rose 30%, dividing incomes by our index will tell us that real incomes grew by about 7.7%.

Here is what the real median personal income looks like over time in the United States:

Plenty of people have struggled in the American economy and continue to. I don’t mean to say they don’t exist. But economists expected that, and only suggested we would see continued growth, as shown above. The 1992 edition of Paul Samuelson’s introductory economics textbook includes this line:

If free trade increases the supply of goods that are produced by particular factors of production or in particular regions, those factors or regions may end up with lower incomes than under restricted trade.

Here, he’s using the term “factors of production” to refer to anything used to produce things, including labor. So, economics students in the early 1990s already knew that the costs and benefits of a free trade agreement like NAFTA would be uneven.

I’ve written extensively to try to show that living standards have risen in the US, and others have done so too. The waves of bad ideas on this subject are hard to fight because you can always nitpick the parts of the economy that have gotten worse and subjectively overemphasize them, instead of weighing them in proportion to their share of spending, as economists do with price indices like the CPI. It’s also easy to lie with pictures:

Any narrative that describes the country as being in material decline is simply wrong, but that’s not the lesson here. The lesson is in Samuelson’s 1992 textbook: economists knew what would go wrong before it went wrong. The mistake, if any, was expecting (or hoping) that American institutions would compensate the losers.

In general, economists have been responsive to new evidence, albeit slowly. Their stubbornness doesn’t appear to stand out in comparison to that of other fields. You can find plenty of examples elsewhere, like how biologists believed in spontaneous generation (the idea that life generates spontaneously from non-living matter) for thousands of years before tests proved it wrong. If there’s any truth to the idea that economists are unusually stubborn, it’s mostly in the inherent difficulty of doing science.

It’s especially difficult to communicate science to outsiders. Laymen seem to believe that economists think tax cuts raise government revenues; really, economists have been trying to get people to stop believing this for some time now. Here’s a Kent Clark Center survey from 2012 where zero economists agreed that cutting the top tax rate would raise revenue.

I could spend endless time trying to give more examples of ideas in economics changing over time, like how Malthusian ideas accurately described the economy before the Industrial Revolution, only to be proven wrong by rapid population growth and simultaneous increases in living standards. But I think it would be better to move on to a more interesting problem.

Are linear regressions meaningful?

Linear regressions are foundational to how economists test their ideas, as seen in the previous post in this series. More specifically, empirical methods like a multiple linear regression with an instrumental variable now make up 70% of the methods applied in NBER and CEPR working papers, as shown earlier in this chart:

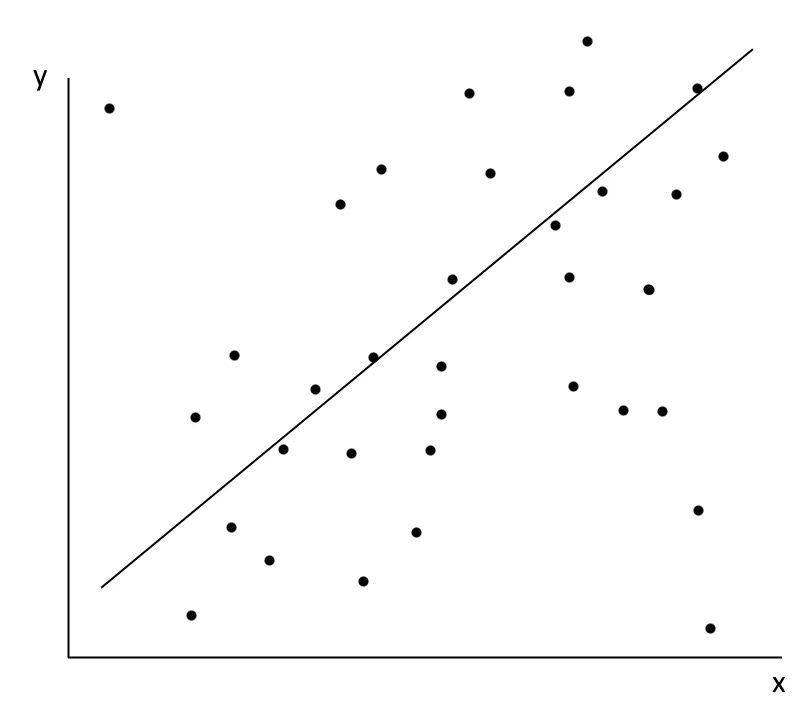

I’m sure most would agree this is a positive change. But in the previous post, I included the image below and asked whether it could be considered meaningful.

With a simple linear regression, we’re trying to model a complex world using a model that tries to predict y-values using only x-values, even though lots of things affect y, and x might even affect y in different ways if other things are different. Here, I would like to provide an example where this works. This should show that linear regressions can be meaningful even in a complex world.

Earlier, I brought up Newton’s second law of motion, F = MA. If you created a Newtonian physics regression, it might look like “A = β*F” where β is just some number we’re looking for called a coefficient, which tells you how force affects acceleration. To estimate the model, we keep punching things and checking how their position changes, measuring their acceleration. Once we’re done, we find that β is some positive number, meaning that more force F is associated with more acceleration A.

Clearly, we’ve lost the plot. Mass should be featured in our formula, too. But something good has happened: we found that force increases acceleration, even though reality is more complicated than that. In truth, β = 1/M, which is not a constant, so we could never identify it by estimating a line. But 1/M is always positive, so greater force always increases acceleration if mass is constant. We identified this correctly by finding that β is positive.

As long as the mass of the object we were hitting was unrelated to the force we were applying, we would come to the right conclusion. If we punched things harder when they were much heavier, we might have found that force seems to have a negative effect on acceleration, since heavier objects move more slowly than lighter ones if you don’t apply force proportionate to their weight.

This is the problem of omitted variable bias that economists try to avoid. We want unobserved things that also affect outcomes, like acceleration, to be unrelated to the things we’re curious about, like force. If they’re unrelated, we can get closer to the truth, even if it remains somewhat elusive. We can know that β is positive or negative, even if it’s determined by other things. So in theory, it really is possible to gain some knowledge about systems too complex for our understanding.

The things economists study are far more complicated than motion, and the methods they use are more complicated too. I think those methods, as featured previously, are very convincing and do a decent job of avoiding the problem of omitted variable bias. At the very least, they’re a great improvement over blind speculation or simplistic storytelling.

Consensus

“Astrology for men” is just one comment I’ve heard when talking about my college major. The other fairly regular response is actually a question: “What school of thought do you prefer?” or something like that. In the eyes of the less-than-fully-informed, economics is divided into schools of thought, including but not limited to classical economics, neoclassical economics, Keynesian economics, the Chicago school, Austrian economics, and perhaps Marxist economics. This makes the field feel more interesting and akin to astrology, or perhaps the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, another form of pseudoscience.13

I think people enjoy receiving new classifications. It adds to their sense of having a unique identity and community with others like them. The same motivation might draw someone to, for example, a Buzzfeed quiz assessing which Harry Potter house they would be in. And I’m not against fun like this.

But I’m against misinformed ideas about economics, and economists generally don’t identify themselves with any particular school of thought. When they do, this signals only differences in framing, differences in focus, or a slight deviation from what most economists believe. I would provide a survey testing this idea if I could; unfortunately, you might only know the truth of what I’m saying by carefully checking the social media accounts operated by academic, PhD-holding economists.

There are no separate schools of thought that disagree on the most important issues. That is reflected in any review of Kent Clark Center surveys of economists or other surveys. The disagreements that do occur often have clear roots in the wording of the question and often appear small on review of the comments made by those surveyed. Major issues in economics, like whether the central bank should cut rates during a recession or the effects of tax cuts on government revenues, have little diversity of thought except on minor points. Economists will disagree on the precise revenue-maximizing rate of income taxation in a country without disagreeing that such a point is definitely less than 100%.

The most agreement occurs on points that feel too boring to mention, like how supply curves almost always slope upward. That simply means businesses in a competitive market are willing and able to supply more of a good if the price is higher. But these simpler points are more valuable than you might think. Evidence points to the same pattern with housing supply, with less housing being produced when prices are forced down, but surveys reveal people often don’t believe this, even when they believe it about other goods. It’s invaluable that economists agree on simple, essential facts like these, even if they’re simple and at first appear unenlightening.

It might be worthwhile to take a moment to look at the aforementioned schools of thought. Classical economics refers to the school of thought in political economy that prevailed in the 18th and 19th centuries, especially in Britain. Many of the ideas of classical economics came from Adam Smith’s book The Wealth of Nations, which still forms the foundation for much of modern economics. It included passages describing supply and demand as well as the need for government intervention in certain areas, like the provision of national defense.14 But as we saw, the Great Depression and other historical developments led to significant revisions in macroeconomic thinking associated with classical economics.

The Austrian school of economics has its own share of contributions to the field, such as Friedrich Hayek’s famed paper The Use of Knowledge in Society describing how, by happy accident, free markets and prices are able to solve the problem of allocating resources based on knowledge otherwise unavailable to a central planner. A central planner, for example, might not know that it would be more efficient to repair a cottage with wood nearby than with concrete from miles away. Prices paid by the cottage owner for wood and concrete make the problem obvious. I rewrote and annotated the entire paper for greater legibility on this blog.

The Austrian school also included advocacy for the gold standard, in which the value of currency is tied to gold by a government promise to provide a fixed amount of gold for every unit of currency. Zero economists on the Kent Clark Center’s panel agreed that a return to this system would improve price stability or employment outcomes for the average American. The problems with the gold standard can be read about elsewhere (an argument from authority like this is a useful indicator, but it isn’t conclusive); the point is that economists did not adopt this particular position that some Austrian economists, in particular Ludwig von Mises, believed in.

Including Marxist economics as a school of thought in economics seems to be a category error. There is no school of thought based around Marx providing answers to most of the questions of concern to modern economists, like “Do minimum wage hikes affect unemployment?” or “Does nominal GDP targeting improve the ability of central banks to provide price stability and mitigate recessions?” Marx also never directly addressed the question of whether there should be a gold standard.

Solving empirical problems mostly requires good econometric work, and the Central Limit Theorem remains true regardless of your thoughts on Marx or the importance of class conflict. Marxists provide a larger narrative of historical progress, but economists are mostly disinterested in long-term historical patterns.

Here is economist Robert Solow, famed for the Solow model of economic growth, describing the issue:

Economics is likely to be contaminated by ideology. For this reason, there are always dissenting fringes within academic economics. Marxism is only the most persistent. There is an Austrian persuasion (a sort of extreme individualism), there are post-Keynesians and neo-Ricardians, and there are many other people who just don’t like what is going on in the mainstream. Nevertheless, there is usually a definite consensus—there is one now—and an accurate picture of the discipline would make that clear.

Of great relevance is the 1995 article “Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of a Survey on Forty Propositions”. Those surveyed were randomly selected from the Economic History Association. Two-thirds disagreed that the gold standard was effective at stabilizing prices and moderating business cycle fluctuations during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with one-third agreeing, mostly “with provisos”, i.e., with conditions attached to their agreement. This contradicts what I said earlier somewhat, but this is also a historical observation rather than a suggestion about what should be done today.

Notably, they overwhelmingly agreed that the passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act exacerbated the Great Depression, with 86 economists agreeing and 14 disagreeing. The idea that the field is divided into schools of thought might lead you to the mistaken belief that economists would be split on issues like these, perhaps with Keynesians supporting the passage of the act, or some other division I couldn’t conceive of.

I’m not sure what, exactly, fuels ignorance on this issue. It may be that people expect too much of economists. Similar problems would arise if you had similar expectations about physicists, hoping they agree on every question you care about, rather than just those they have extensively studied. I would not consider physics to be less meaningful if physicists disagreed about whether the universe is a mathematical structure, as hypothesized and advocated for by physicist Max Tegmark, or if they disagreed about whether that is even plausible.

Some might still be annoyed by the contrast between what I’m saying about the scientific nature of economics and the disagreement the field clearly has. If you asked 100 physicists whether hydrogen bonds explain the surface tension of water, it’s unlikely that 14 of them would disagree.

The real problem is that political systems create a natural tendency for the issues of most concern to people to become those most difficult to solve, unlike other fields. Whenever governments are considering passing a bill into law, they weigh the costs and benefits. The US government considers an odd reweighting of the costs and benefits of a policy to the country as a whole, with less-populated states receiving more influence, for example. But in some cases, the benefits of a particular policy are so clear and so broad that it is quickly passed into law and never touched.

One good example is national defense. Very, very few people in the US spend time discussing the abolishment of the military. Economists have a clear explanation for why: the military provides a public good, national defense, which would not be provided if not for its existence, due to the free-rider problem. Without government funding, the military would struggle to convince people to pay them voluntarily, since everyone would prefer to let others foot the bill. So the military has always been there, and while its funding as a share of GDP has fallen slowly for decades, it still remains. Any other policy with such clear benefits receives the same treatment. On these issues, few people ask economists for their opinion or look for a consensus.

Compare this policy to the minimum wage. Rather than benefiting everyone, the policy has clear winners and losers. The winners are most workers, while the losers are the seemingly few workers who are left unemployed as a consequence, and the businesses who have to pay more for labor. It should be expected that at times economists disagree on the exact costs and benefits of the policy and whether it is good on net. What’s unexpected is the level of agreement they really do have at times, with, for example, only one economist among 42 agreeing that raising the federal minimum wage to $15 per hour would substantially increase aggregate output in the US.15 Issues like the minimum wage, with winners and losers and complicated effects, are the issues the public most wants economists to provide clear answers and recommendations for.

Other sciences generally don’t suffer from this problem. There is not much of a natural tendency for public attention to be pushed to the most difficult to resolve issues in physics, zoology, paleontology, or almost any other science. People are happy to enjoy fun science videos about physics concepts established a century ago, and expect only that the laws of physics don’t suddenly fail while a plane is in flight. They don’t think very often about the reason why practically every government redistributes income when charity exists.

If the most elementary and well-agreed-upon ideas in economics were as interesting as those in physics, it might not be considered so easy to dismiss. Compare the equation of exchange in monetary economics, MV = PQ, to Newton’s first law. Newton’s first law tells you that an object in motion stays in motion, and it’s surely obvious to physicists. Despite this, people are still amazed and confused when confronted with a situation where a man jumps on top of a moving vehicle.

It would be helpful for people to know that P = MV/Q, i.e., the price level is strictly determined by the money supply, the rate at which it changes hands, and how much we produce. This is an accounting identity, a tautology in the terminology we introduced earlier. Almost nobody outside of economics can give you this formula from memory. They do know that inflation was unusually high during the Biden administration, and expect economists to have known this would happen before the Biden administration’s legislative agenda was passed. To create an analogy to physics, you might as well expect them to know the location of the jumping man after five seconds while only knowing the force of the jump and the weight of the man without the direction, speed, or pressure of the wind.

By this point, I think we’re ready to move on to the next section. But if you still aren’t convinced, you can examine the contents of this paper, “Views among Economists: Professional Consensus or Point-Counterpoint?” by Roger Gordon and Gordon B. Dahl:

Based on our analysis, we find a broad consensus on these many different economic issues, particularly when the past economic literature on the question is large.

Perhaps the most relevant section:

The first question we face in the analysis is how to define differences in views among our panel members. Consider for example the responses to the question asking whether the Fed’s new policies in 2011 will increase GDP growth by at least 1% in 2012. The responses were 41% “uncertain”, 37% “disagree”, and 17% “strongly disagree”. Initially, we assume that these responses imply consensus, since no respondents “agree” even though respondents differed in their extent of disagreement with the statement.

By this definition, there is an extraordinarily high level of consensus among our Panel members. Only 6% of the responses in our data violate this definition of consensus, responding “disagree” when the consensus is “agree”, or conversely. Similarly, for 32 out of the 80 questions, there are no such disagreements.

Scientific norms in economics

If you are especially cynical about science, you might prefer the sociology of science to the philosophy of science. Rather than asking what makes something scientific, sociologists focus on the behavior of scientists and the way they interact with each other. From their perspective, it might be that what matters in comparing economics to other forms of science is comparing the norms that prevail among economists to the norms that prevail among chemists and physicists. This also leads us into some additional criticisms one might have of the field.

According to sociologist Robert Merton, the norms that govern scientific communities are universalism, communism, disinterestedness, and organized skepticism. We’ll look at each in turn.

Communism

Ironically, this is the one norm described by Merton that seems to clearly apply to economics and just about any other field. Communism is the norm of common ownership of ideas and results, and clearly, there are few restrictions on the ideas and results you can use for doing economics. Supply and demand was never owned by Adam Smith, and you are free to cite Daron Acemoglu as many times as you’d like. I don’t think I need to spend more than a paragraph talking about this. There are exceptions, like proprietary data, but I rarely hear about difficulties arising from a lack of idea communism.

Organized skepticism

Organized skepticism is the second least restrictive of the norms and refers to the norm of scientists continuously questioning each other’s results. David Card’s study of the Mariel boatlift of Cuban immigrants into Miami provides us with a good example. Card found that immigration had no effect on wages there, but Labor economist George Borjas criticized and reappraised Card’s study, writing a paper reanalyzing data on wages in Miami. He found that “The wage of high school dropouts in Miami dropped dramatically, by 10 to 30%, suggesting an elasticity of wages with respect to the number of workers between -0.5 and -1.5.” This was then followed up with another paper about the same event from Giovanni Peri, finding no such impact. Economists are bickering types, which is very good for hunting down the truth.

I could also point to Card’s study of the minimum wage hike in New Jersey and the response from Neumark and Wascher, but further examples would not really prove the rule. Without somehow taking a random sample of all papers published in economics and checking whether they faced serious criticism, one can’t really know whether organized skepticism prevails, except by slowly gaining confidence that it does as you study the field. I have a lot of confidence in it now.

Universalism

Universalism is the idea that the personal attributes and social background of a person shouldn’t influence the value of their ideas. More generally, ideas are valuable only for their content. One way we might check to make sure a field is universalistic is by looking at the diversity of its most celebrated thinkers. The problems with doing this come from a couple of forms of omitted variable bias: first, competency is weakly correlated with demographic characteristics, so we should expect some demographics to show up disproportionately often, and second, demographic characteristics are correlated with one’s choice to enter a field, resulting in the same pattern. So it’s worthwhile to look at more serious work on discrimination within the field of economics rather than gazing directly at its very white, male, wealthy makeup.16

To make this simple, I’ll compare discrimination within economics to discrimination within the sciences as a whole. If you can tolerate the scientific status of most of the sciences in spite of some harmful forms of discrimination, showing that discrimination within economics is not much worse or better should show you that this is not a useful point to make against economics in particular.

This is an area where economics seems to do well. A 2023 article in PLOS Biology, a peer-reviewed journal, looked at millions of authors to measure how much more frequently men are cited than women across many scientific disciplines. In their sample, there were 1.88 times as many men among the authors analyzed as women, and there were 3.21 times as many men among the top 2% of authors by citations. They found substantial differences between fields, with men showing “more than 3-fold relative overrepresentation among top-cited scientists than in the overall count of authors” in economic theory and econometrics. These are only two subfields of economics, so it’s not clear what the field as a whole looks like, but this is a bad sign.

A similar result was found by Erin Hengel in 2019, with male-authored papers in economics getting cited more often.17 However, Hengel found that this was driven by a small number of highly-cited papers from Nobel winners written in the 1980s. Once these outliers are removed, “female-authored papers are actually cited more.”

But it’s not all sunshine and roses: the author had previously found that women seem to be held to higher standards in the peer review process, explaining both their underrepresentation in economics journals and their greater likelihood of getting cited. Women also appear to be viewed differently in economics, with letters of recommendation for women economists18 being more likely to include language describing the economist as hard-working and less likely to include language describing them as having great intellectual ability.

There are substantial problems of bias, but I have hope that things are improving. That this work is being done at all is a good sign. One of the more recent Nobel prizes in economics was won by a woman, Claudia Goldin, “for having advanced our understanding of women’s labour market outcomes”. We’ve also seen that any rejection of economics on this basis would reject other sciences as well; for further evidence, consider the great underrepresentation of women among winners of the physics Nobel. I would write about discrimination against ideas in economics on other (irrelevant) bases if I had more time, but there’s too much to talk about.

Disinterestedness

Disinterestedness is perhaps the most idealistic of the norms Merton described. It’s the norm of acting for the benefit of a common scientific enterprise rather than your own personal gain. I’m not sure how important this is to the validity of ideas within a field, but I should at least talk about it a little.

Economists would be the quickest of all scientists to counter that this is unnecessary for good results in the aggregate. Like I described before, the field has its roots in Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, which celebrates the “invisible hand”, a metaphor for how people help one another through mutually beneficial exchanges when they are constrained by private property rights.19

Interestingly, philosophers of science have expressed similar views about the sciences. Philosopher Thomas Kuhn, famous for his ideas about science evolving through paradigms, also wrote about how scientific progress can occur even if individual scientists are narrow-minded and dogmatic. This is not quite the same as self-interested scientists creating a disinterested community, but it’s analogous.

Do economists act for the benefit of science rather than their own personal gain? I think it’s both. When the two come into conflict, I suspect there are problems, but practically everything I’ve written about can be taken as good reason to believe they act for the benefit of science anyway. By happy accident, the parts of this post about evil statistical techniques and fraud succeed this one and will help you decide whether economists are remarkably selfish and non-disinterested.

P-hacking

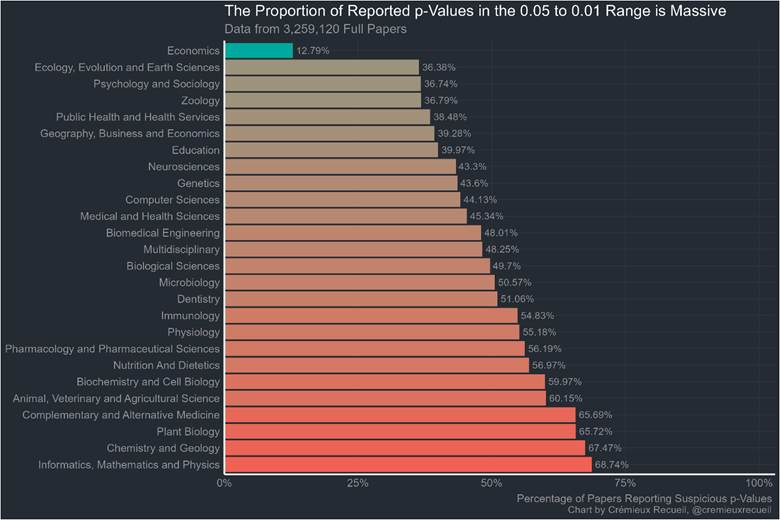

They aren’t. Here’s a chart that makes me especially proud: