How Welfare Works (And Doesn't)

The point of this post is to talk about what purpose the welfare state would ideally serve, where it fails, and what we could do to address poverty instead. I’ll focus more on theory than evidence, but include plenty of links one could follow for more evidence and less theory. This was originally written for a potential application to work at the CATO institute, a libertarian think tank.

Fairness Is a Public Good

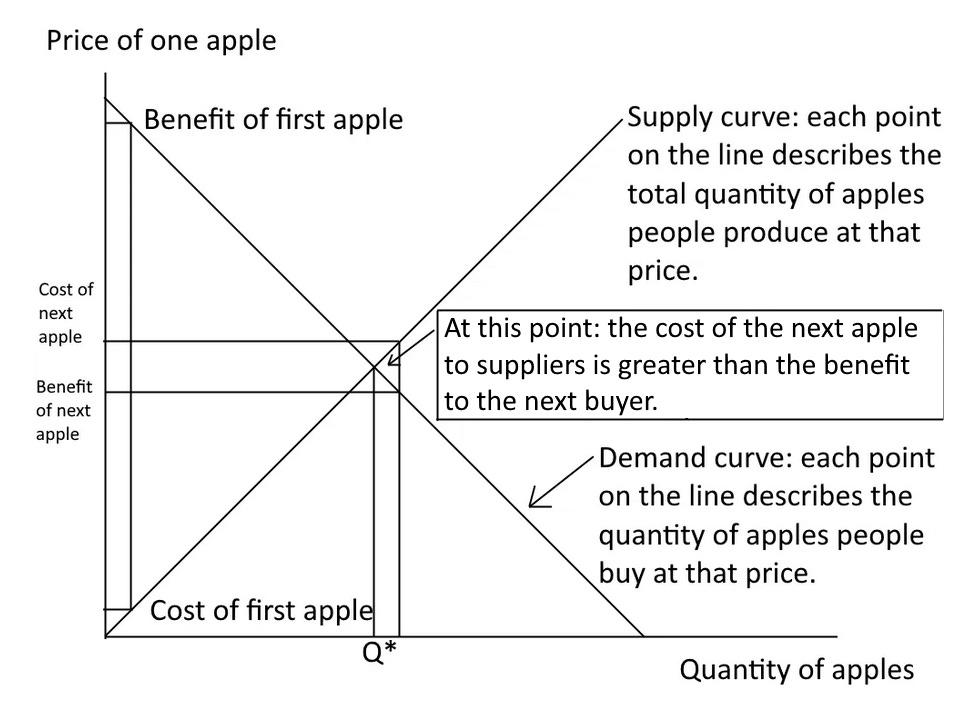

Two essential characteristics of a good are whether it is “excludable” or “rival.” A good is excludable when you can exclude people from the benefits of it. A good is rival when one person enjoying it prevents someone else from enjoying it (so you “rival” each other in enjoying it). A simple example is an apple: you can give an apple to one person and not another, and that person eating the apple completely prevents someone else from enjoying that same apple. These two characteristics make apples a private good. These goods have a nice quality: if the government protects people’s property by force, a free market will produce the efficient quantity of apples.1 That means it will maximize the “profits” to society: the difference between the benefits of the apples produced and the cost. Here is a supply-and-demand diagram of this situation. The vertical axis describes the price of an apple, and the horizontal axis describes the quantity of apples produced. Keep in mind that throughout the post, perfectly vertical (or horizontal) lines are used to point to specific quantities and prices. They don’t represent relationships.

Notice, in this graph, that producing the first apple is very profitable for society: whoever values apples the most will buy it and whoever can produce that apple at the lowest cost will produce it. (This may not exactly happen in real life, but certainly the people who value apples the most will tend to be the first to buy them, and the people who can produce apples at the lowest cost will tend to be the first to produce them.) The difference between the benefit and the cost is thus very large. This difference, which we call surplus, diminishes as more apples are produced until total surplus is maximized at Q*. We know it’s maximized there because producing the next apple would have a greater cost (shown by the supply curve) than benefit (shown by the demand curve).

Why does a free market produce the optimal quantity? If you assume that too little is being produced, producers can gain by producing more: they can cut prices and produce more apples. They’ll be willing to do that because the supply curve is underneath the demand curve at every quantity less than Q*. (That means the cost of producing another apple is less than the maximum price they can charge for it.) If they’re producing too much, they’ll be forced to sell at a lower price than what they require to be willing to produce that much, because the supply curve is above the demand curve for quantities greater than Q*. It’s only when supply meets demand at Q* that there is no pressure for anyone to change what they’re doing.

If you still don’t understand, try thinking about it in terms of prices. If the price is too high, producers will be willing to produce a lot, but people will be willing to buy very little. (Producers like higher prices, but consumers dislike higher prices.) So everyone can gain by bringing prices down when they’re too high. If the price is too low, producers won’t be willing to produce much, even if people are happy to buy a lot. So everyone can gain by raising prices. At the equilibrium price where supply and demand meet, producers produce the optimal quantity Q*.

There’s just one problem here: the benefit to a person who might buy an apple is represented as what they’re willing and able to pay for it. The forces of supply and demand naturally bring us to the efficient result in terms of the prices people are willing and able to buy and sell at, but is this the result we’d like? What about someone born with a disability who can’t find a job? What about someone who has fallen victim to some form of labor exploitation and is paid too little? Then, what they’re willing and able to pay will be lower than otherwise, and for (what most would consider) a bad reason.

The nice thing is that people who face misfortune often receive a lot of help from their family and friends and can actually find jobs sometimes. But there are always edge cases that feel deeply unfair. So now let’s bring in the core concept of this post: fairness is a public good, a good that is non-excludable and non-rival.

What that means is that unlike an apple, when we make an outcome more fair, everyone who likes fairness gets to enjoy the knowledge that things are more fair, and nobody who enjoys seeing that fairness is prevented from enjoying it by someone else enjoying it. How nice! Fairness is like a lighthouse: everyone gets to enjoy its shine no matter what.

But because fairness is a public good, a free market does not create the optimal amount of it. The narrower interpretation of this is that a free market does not create the optimal amount of spending on welfare, which we call charity when done by a private actor.

Why is that? The simple answer is that the non-excludability of charity means it has very large external benefits, benefits to people who aren’t involved in giving or taking it. That means our previous supply-and-demand diagram wouldn’t accurately describe charity. Before, the demand curve for apples represented both the private benefits of apples and the benefits of apples to society. That’s because all of the benefits of an apple are enjoyed by whoever buys the apple, and whoever buys the apple is a member of society, after all. But now, the private benefits of charity and the benefits of charity to society aren’t the same: a private company’s efforts to help the needy make everyone else better off, too.

The optimal quantity of charity for society is still where society’s demand curve meets society’s supply curve. But the quantity of charity that will actually be produced in a free market is less than that: it’s where the private demand curve meets the private supply curve.2

This is the essential problem of charity (or welfare). Most people want to help the needy, but there’s a free-rider problem: you can enjoy the benefits of charity without giving any money yourself. So if you just let the free market do its thing, you’ll get a decent amount of charity/welfare, but not the optimal amount.

I don’t know what the optimal amount of welfare is; nobody does. But you should notice that, setting aside debates about its effectiveness, we would expect people to argue we need more welfare if they personally benefit a lot from it (high empathy or they’re poor), and argue we need less welfare if they benefit very little (low empathy or they’re rich). This produces a core political conflict we see all over the world: people who don’t feel as much of a benefit from seeing a poor person helped (or even feel upset when they see charity) push back against redistribution, while people who feel more of a benefit from it push for more. These are typically right-wingers and left-wingers, or conservatives and liberals, respectively. Genuine concern about the effectiveness of welfare does exist, but I would expect few people to be informed enough for that to be their true motivation in talking about cutting spending.

So, how effective is welfare in the United States?

There Are Problems With This, Unfortunately

The cost of supplying charity/welfare doesn’t just depend on natural factors like how easy it is to identify someone living in poverty. That’s because when you split charity and welfare into two markets, the market for welfare looks different:

I’ve positioned the supply curve higher (any given dollar of welfare costs more to provide than a dollar of charity). You can take a dollar from your pocket and give it to a friend in trouble or a homeless man on the street. The government can take the same dollar, give 1-8% of it to various intermediaries, lose some of it to fraud, then provide the rest to someone else, often in the form of a service like healthcare. That last bit is important: if you give someone one dollar of medical benefits, that may not be the optimal choice of spending.

Allow me to elaborate. The relevant paper here is “The deadweight loss of Christmas” by Joel Waldfogel. Every time you give someone a gift, you probably didn’t pick what they would have bought with the same amount of money. Waldfogel estimated that because of this difficulty, between a tenth and a third of the value of every gift is destroyed. (To be clear: this means that you might have bought someone a $10 gift, but making the exact, correct choice for them would typically give them $1 to $3.33 in extra value.) The government suffers from this same problem when it provides welfare in the form of a service like Medicaid rather than a cash benefit: the recipient may have preferred to spend some of that money on something else.

Governments and charities alike suffer from the Christmas problem because it’s easier to get people to donate (or vote) if you spend on a service rather than give it directly. “We’re trying to make sure the poor get healthcare!” is a better tagline than “Let’s give to the poor!” because people are more concerned about guaranteeing access to necessities than giving poor people money. There’s also a common perception that poor people will spend that money on something they shouldn’t. Popular media still depicts the poor this way: the first episode of the latest season of Squid Game shows poor people repeatedly choosing to take a lottery ticket instead of bread.3 Parasite depicts a poor family as a group of violent frauds.

So far, I’ve given fairly regular talking points about welfare systems. But the biggest problem is not administrative costs, not fraud, and not Christmas-type losses: a lot of welfare spending is really insurance spending that doesn’t contribute toward moving us to the optimal level of charitable giving.

Most Americans will fall below the poverty line at one point in their life or another. Social mobility may be lower than we’d like it to be, but there is still movement up and down the distribution of income. Poverty can be a consequence of losing a job, divorce, and other normal events in one’s life. And, to give you something to be glad about, just 6.4% of people born into poverty in the United States remain in poverty for their entire lives. All of this implies that people who take from Medicaid and other forms of welfare typically contribute to the system at some other point in their lives.

The money that circulates through the federal government and back to Americans through welfare programs would, in the optimal case, not always have been spent on charity. It would typically have been saved for retirement (as in the case of money put into social security), saved for periods of unemployment, or spent on insurance.

That brings us to a simple problem with government spending on “welfare”: it creates a problem rather than solving one. Savings and insurance are both private goods. You don’t need the government to intervene to optimize them: each person can just save as much as they would like and buy things like health insurance if they’re worried about unexpected problems. When the government instead decides to force people to save and buy insurance (by raising taxes and spending that money), there is a risk of over-saving or over-spending: if the government doesn’t identify the optimal amount of something and overshoots, they’ll force someone into a Christmas loss. Alternatively, they may save too little, though in theory that can be alleviated by a taxpayer choosing to save or spend more.

It should be said, however, that social security is not quite an insurance program, nor are any of these programs. They are only similar to insurance, not identical. Social security redistributes from the young to the old. Money you put into the system may (hopefully) give you a right to take out of it later, but it isn’t held onto until you retire. It’s given to current retirees.

Normal Solutions

I won’t spend too much time on this part because it’s been done before. It would be wise to (perhaps only partially) privatize social security. Medicaid is both a non-ideal solution to impoverishment and has been designed in a way that encourages the States to engage in fraud and spend more than what’s optimal. Some have recommended that its budget should be cut, but I would certainly only recommend this if that money were forcefully redirected towards optimizing the level of redistribution.

Let’s change directions. Poverty is defined by material deprivation (in varying ways) and typically involves periods of unemployment. Both of these things are relieved by increasing opportunities for employment, and a great way to do that is to eliminate most forms of occupational licensing, i.e. government-mandated programs that require people to meet certain requirements before working.

You probably think that’s a bad idea. Shouldn’t we have minimum expectations for people at work, like doctors and lawyers? True as that is, we don’t need the government for that. You don’t expect someone selling you a taco to be licensed because tacos rarely cause food poisoning. That’s true because of competition among restaurants, and because restaurants are forced to take on the costs of food poisoning, paying large sums if they’re met with a successful lawsuit. Much the same can be said about doctors. Private organizations can always provide doctors with a seal of approval that lends them trust, and doctors that fail to do their jobs tend to lose money when people seek out other doctors (or get fired for their incompetence, again because people will turn to other healthcare providers and their employer will lose money).

And why would you trust the government to provide that seal of approval more than a private company, anyway? In either case, you freely decide whether that certification is useful information or not. There are multiple certifying organizations you can choose from to decide who is trustworthy. The government, meanwhile, provides just one seal, and there’s no reason to expect it to be inherently more trustworthy. As an example of a private organization providing certification, we already have the American Board of Medical Specialties, which has certified doctors since 1933.

When we license professionals like these, here’s what’s really happening:

(I’m not sure if “market salary” was the right label for this graph, since in either case a market exists, but you get the idea.) With licensing, we add an extra cost to becoming a doctor, the total number of doctors hired goes down a little, and the salary paid to doctors goes up a lot. I could just as well describe this situation with a model of a cartel, but I’d prefer to keep things relatively simple.

What you should understand is this: the law of demand tells you that the highest price that can be charged in a market goes up when the quantity being sold goes down. That’s just another way of saying businesses have to cut prices if they want to sell more of something, because people don’t like spending money. So if you force down the number of doctors through licensure, salaries go up, and somebody has to pay for that—you!

Licensure is not helping the little guy at all. It creates a privileged class of workers everyone else has to pay for. Talking about this is difficult, of course, since physicians are nominally some of the most moral and practically useful workers in the world. The greater difficulty is that doctors, lawyers, and other licensed professionals have plenty of money to spend on lobbying when their position is challenged. There is broad agreement among economists on this issue and economists have known about it for a long time, with there being work on it dating back to 1945.

Licensure is required for 22% of jobs as of 2021. It would be one thing for employers to seek the most well-trained workers; it’s another when those workers attempt to keep out competition by getting the government to require a license for you to join the industry. Convincing the public that occupational licensing is wholly unnecessary would be difficult, but we can certainly manage to eliminate licenses for makeup artists and barbers. (Did you even know that people often need a license to cut your hair? You wouldn’t assume so because of how unreasonable it is.) Lowering these barriers to entry would both make it easier for those who might otherwise be impoverished to land a job, while simultaneously lowering the cost of various services.

A counterargument you might hear is that if licensure is keeping salaries high, it’s what we need to keep workers afloat. This is silly. Licensed professionals typically make more than what the typical American makes, and the typical American makes plenty. Worse, licensure creates economic losses: the nice maximization of total surplus I mentioned earlier goes away. That means some people who otherwise might have received healthcare don’t get it, and some people who might have gladly provided it don’t get to. If you want to take care of workers, we can instead eliminate licensure to create more surplus (normally we’d just say economic growth), tax those gains, and use them to fund wage subsidies for low-income earners. Growing the pie and redistributing it is better than shrinking it while trying to redistribute it.

A Weird Solution

If you want to move toward the optimal level of welfare spending at the lowest possible cost, replace all welfare spending with massively increased tax deductions for charitable giving. By that, I mean let taxpayers deduct an average of up to 10% of their incomes from their taxes if they spend on charitable giving. Provide an automatic bonus for anyone who makes such a deduction, proportionate to their level of income. (This may seem strange, but it’s to cover the potential costs of spending time on searching for a preferred charity, rather than working, and to encourage people to engage with the system in the first place.)

The essential idea here is that we should decentralize welfare. One of my previous posts, on Friedrich Hayek’s essay “The Use of Knowledge in Society”, is fairly relevant here. Ideally, we would make a government board of experts who can figure out what the best way to optimize welfare spending is. But selecting members of such a board would not be easy. They would also have to figure out the optimal amount of spending in various localities, seeking out struggle and differentiating it from fraud as well as they can in a country of 335 million people.

The best we can do is to instead have such a government board approve options for Americans to choose from, certifying charities, ideally with a low bar. Keeping that bar low would, of course, be difficult; charities would themselves want to keep out competition as much as possible so they can get their hands on more government money.

Because these deductions have to be covered with other taxes, this system would be taking tax money and turning it into charitable giving—“forcing” Americans to spend on charity and preventing the free-rider problem faced by public goods. This could be funded by cutting out other forms of welfare spending.

Epilogue

This post is different from what I normally write. I’d usually prefer to advocate for more Medicaid spending, but that’s just because I’m a liberal who is willing to tolerate the costs of doing so even if it means the impoverished only get a little more help. But there’s plenty to be said about the benefits of economic freedom, rather than redistribution on its own, to the typical person living in poverty. These people are not infants who need help at every turn—they are typically impoverished temporarily as they seek work, or they otherwise work a job that doesn’t pay too well. Making sure these people have escape routes, benefit from doing the work they do, and pay lower prices is one of the best ways we can help them.

But only if you also assume they don’t have external costs or benefits, which is true, but not the main focus here. As for why property rights are necessary here: if you don’t have government protection, people can simply take the tools and equipment of apple farmers, which reduces the total quantity of apples produced. We don’t want that, of course. Usually, it would be the government itself that expropriates that equipment, as described in e.g. Why Nations Fail.

In the diagram, the supply curve looks different. This is because I’ve assumed (fairly reasonably, I’d say) that the cost of one dollar of charitable giving is a bit more than a dollar, and rises slowly the more is given.

If you think that’s a reasonable choice, you should learn what expected value is. Here’s an example. If 99.9% of lottery tickets lose and they each cost $5, and the jackpot is $1,000, then the expected value of a lottery ticket is:

-5*0.999 + 1,000*0.001 = -$4

You can expect to lose four dollars on any given lottery ticket, on average. In the real world, the expected values look similar, except the odds of a jackpot are even lower (and the jackpot itself is much higher). But the math is essentially the same; higher jackpots always have lower odds, and the lottery is able to profit off of its sales.

Buying these tickets for fun is fine. Buying them as an investment is not. Encouraging people to buy these to escape poverty is evil.