The right thing to do is often not what you're expected to do

Contra Bryan Caplan on insect death

I could begin this post with what inspired me to write it, but I think a made-up example is the right way to go for moral philosophy.

Suppose you are given a not-the-trolley-problem problem wherein you must choose between killing one person and killing three people. There is absolutely no difference between them, and there is no trolley. You have a gun, and Jigsaw is forcing you to choose. You should obviously kill the one person rather than the group, unless you’re an antinatalist who thinks life is so bad that it can’t be worth living or something.

Now take the same example, except this time the one person is your mom. Maybe your mom is an exceptionally good person who saves lives, and if that’s the case, assume the other three people are equally good for the world. The only difference is that she’s your mom, and you have that strong emotional and genetic connection that most people have with their mom. It seems clear to me that two things are true: (1) the right thing to do is to kill your mom, and (2) you are absolutely not expected to do the right thing. I wouldn’t kill my mom! I would just kill the other three and live with the guilt.

Let’s now turn to a more famous thought experiment in moral philosophy originating in a paper by Peter Singer, and it goes something like this: you encounter a child drowning in a shallow pond, and you can wade into it and get your clothes all muddy. It’s an $800 suit from Charles Tyrwhitt, so it’s no small thing, but if you don’t ruin the suit, the kid is going to die. We can expect practically everyone to agree that the right thing to do is to save the kid. The problem, Singer argues, is that the principle you’re relying on that says you should give up something of relatively small value, like the suit, for something of great worth, like the life of a child, also tells you to give much larger sums of your money to charities serving people around the world. But nobody does that, so it seems that everyone in the West is a terrible person.

In high school, I took IB Theory of Knowledge because I was interested in philosophy. At one point, our teacher showed us a video posing this problem to us, with the kind of “Gotcha!” attitude you would expect. Because I was very moralistic and didn’t like the idea of losing my position as a Good Person™, I decided to show off. With what little money I had saved from allowances and gifts, I donated $500 to Deworm the World, since it was GiveWell’s most efficient life-saving charity at the time, and that was the price of saving the life of a child under five. I then emailed the teacher about it for maximum spite.1

But my brief effort at saving a life was not so impressive. In his paper “Sometimes there is nothing wrong with letting a child drown”, Travis Timmerman argues that Singer’s analogy isn’t appropriate, and I’m inclined to agree. Most people don’t encounter drowning children frequently, if at all, and when you hear about this thought experiment, you assume you haven’t been frequently encountering drowning children. Change that, and it seems that you should let lots of children drown. Here’s Timmerman’s analogous case:

Drowning Children: Unlucky Lisa gets a call from her 24-hr bank telling her that hackers have accessed her account and are taking $200 out of it every 5 min until Lisa shows up in person to put a hold on her account. Due to some legal loophole, the bank is not required to reimburse Lisa for any of the money she may lose nor will they. In fact, if her account is overdrawn, the bank will seize as much of her assets as is needed to pay the debt created by the hackers.

Fortunately, for Lisa, the bank is just across the street from her work and she can get there in fewer than 5 min. She was even about to walk to the bank as part of her daily routine. On her way, Lisa notices a vast space of land covered with hundreds of newly formed shallow ponds, each of which contains a small child who will drown unless someone pulls them to safety. Lisa knows that for each child she rescues, an extra child will live who would have otherwise died. Now, it would take Lisa approximately 5 min to pull each child to safety and, in what can only be the most horrifically surreal day of her life, Lisa has to decide how many children to rescue before entering the bank. Once she enters the bank, all the children who have not yet been rescued will drown.

Things only get worse for poor Lisa. For the remainder of her life, the hackers repeat their actions on a daily basis and, every day, the ponds adjacent to Lisa’s bank are filled with drowning children.

This is much closer to the real-world case. Rather than experiencing the drowning child event once, you experience it all the time. Every time that you’ve had money beyond what is necessary for you to live, you’ve had the opportunity to spend it on saving lives rather than making your own slightly better. The consequence of following Singer’s principle isn’t losing $800; it’s losing potentially millions of dollars over the course of your lifetime.

So why do I think my $500 donation wasn’t so impressive? Because while Timmerman is right to argue that the analogy is wrong, he’s incorrect in thinking that sometimes, it’s ok to let a child drown. Every single time Lisa experiences this problem, she really is morally obligated to save the children, up until everything she owns is gone. The principle Singer mentions is simply correct. The same is true of wealthy Westerners who can sacrifice far more to save lives around the world. My donation in high school might have been a good thing to do, but if I always did the right thing, I would have donated again two weeks ago instead of buying a Nintendo Switch 2. Malaria nets are more important than Mario Kart.

I think that most people, on encountering problems like this, think there must be something wrong with Singerism just because the idea that we are morally obligated to give up our lives of relative luxury is so discomforting. I disagree. I think that there is a very big difference between the right thing to do and what you’re expected to do.

Earlier today, Bryan Caplan made a post referencing an older argument of his that animal suffering is not morally important. In his words:

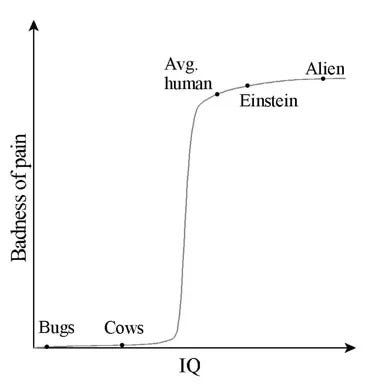

Nine years ago, I wrote this piece arguing that insects provide a strong reductio ad absurdum to Huemer’s view. If animal suffering is morally important, then insect suffering is morally important, which implies that even the most seemingly innocuous activities — driving a car, building a house — are morally monstrous. Since this conclusion is absurd, we should reject one of the premises. Namely: We should reject the view that animal suffering is morally important. Instead, contrary to ethical vegetarianism, the badness of suffering heavily depends on the intelligence of the sufferer.

This is not the right solution to the problem. The premise we should reject is not that animal suffering is morally important, but that people should be expected to always do the right thing, or even to do the right thing 90% or 80% of the time.2 Driving a car is morally monstrous if it causes lots of suffering for animals. I just don’t expect people to quit driving for that reason, and I don’t plan on chastising anyone for it. Every single person on Earth lives with some level of tolerance for morally wrong behavior. Even vegans, who are especially intolerant to moral wrongs, probably don’t put in so much effort that they discover just how evil it is to eat honey. But if extra effort has even the slightest chance of revealing such a moral wrong, the right thing to do is to spend your life reading moral philosophy and minimizing your harm to the world. Nobody is expected to do this.

A lot of bad ideas have come out of refusing to acknowledge this simple truth. Here’s what Caplan followed up that quote with:

You heard it here first, folks: I probably did better on the ACT than you did, so it’s worse when I feel pain than when you feel the same pain. It seems like this new argument is, like the one Caplan is criticizing, destroyed by a reductio ad absurdum. Under the rule of this graph, you should always prefer to cause pain to a dumber person, even if they are only slightly dumber, for unclear reasons. It’s also pretty much fine to kill a human baby!

I nigh-exclusively make sense of the way people talk about this issue through kinship bias, or kinship preference, if you will. Members of the same species tend to protect each other for natural selection reasons, and this is clearly true of humans in particular. If someone is especially close to us genetically, such as by being our child, we expend a great deal of effort to save them. We see movie stars as heroes after they kill dozens of terrorists to protect their kid, and like to imagine ourselves in their place, fighting for what we care about most. Most people give little thought to the struggles and national aspirations of Palestinians.

Uh, sorry, did I say Palestinians? I meant the Kurds. Or the Tibetans, Uyghurs, Rohingya, West Saharans, Tamils, Chechens, or Kashmiris. There are millions of people all around the world with struggles like those of the Palestinians, which we think little about simply because our government has made a conscious choice to assist the Israelis to get intelligence and other benefits in return. Next time you’re getting oppressed, ask the US government to assist your oppressor for free sympathy. The marginal benefit of supporting each group is the same in each case, or at least not too different, but the difference in attention is massive. It’s so big for the same silly reason that the problem I mentioned earlier is magically transformed when a trolley is on its way to kill three people.

There are certain forms of kinship preference so strong and common that we see nothing wrong with acting in accordance with them. Cows are slaughtered in the millions every year. While watching the horror documentary Dominion about factory farming, I had the massive displeasure of seeing a baby cow separated from its mother and left to die in 100-degree heat. The mother cried and wailed as it was carried away on a truck. We don’t accept these things because they’re fine from a moral standpoint; we accept them because we’ve been naturally selected to. A being that dedicates all of its time and energy to maximizing the well-being of anything that might be capable of experiencing pain and pleasure would not be good at reproducing.

Much to my annoyance, these discussions frequently leave aside the hard problem of consciousness. There’s no clear relationship between the experience of being alive and the physical states we associate with being alive. I’m human, and I have all of the mental faculties associated with being human, so it seems like other people should also experience pain and pleasure the way I do. But there is no way that this can be empirically verified, because I will only ever experience life from my own perspective. Observing someone else experiencing pain verifies that they experience pain just as much as observing ChatGPT saying that it experiences pain shows that it experiences pain.

Likewise, I can’t know whether cows or bugs experience the world in any capacity. We only infer that they experience it based on the same similarities we use to infer that other people experience it: they have brains, make sounds and movements correlated with whether they’re being harmed to helped in some way, and they look cute and human-like in some ways.

Despite all of that, I’m still very confident that other people experience pain, and so do animals and insects. In the video Caplan linked, Matthew (Bentham’s Bulldog) thinks this can be turned into a science and relies on work looking at the correlation between expressed pain and active neurons in the brain. From that, we can try to guess how much pain is experienced by animals. As you might guess, this is all very iffy to me. I think it’s much better to look at the consequences for an animal’s ability to survive and reproduce, since there’s generally a relationship between that and how much pain we feel (e.g. we feel a lot more pain from getting kicked in the balls than anywhere else because it’s a vital organ for reproduction).

So, weep for the cows and insects of the world. They have it rough. But I won’t get mad if you decide against donating to the shrimp welfare project. Resources are scarce, and it’s (pleasantly) surprising when someone aims to use all of theirs to be maximally moral.

I write this as if he were a bad person, but I loved that guy, and this whole interaction was cheerful and silly.

It’s not clear how large the number of morally consequential decisions is and how you might come up with this percentage.

> The premise we should reject is not that animal suffering is morally important, but that people should be expected to always do the right thing, or even to do the right thing 90% or 80% of the time.

Should we be individually and collectively trying to increase the percentage from X to X+delta each day? Is there a hard ceiling? Or a band that is acceptable?