Mamdani 2025: You'd Better Hope They're False Promises

Reviewing the platform of New York City's most likely next mayor

I’m of the opinion that politicians generally do what they say they’re going to do. The caveat is that they’re restrained by their opposition, who can vote against their proposals, and by institutions, which impose requirements like a 60% majority in the Senate to break a filibuster. But presidents generally make a good-faith effort to get things done, and members of Congress overwhelmingly vote in line with their party’s platform. So it’s reasonable to expect Mamdani’s actions as mayor to reflect his platform. What should New Yorkers expect him to try?

Itsy-bitsy housing construction

Mamdani is focused on lowering the cost of living for working-class New Yorkers. To do this, he’s included some nonsense designed to make me angry by lying:

We need a lot more affordable housing. But for decades, New York City has relied almost entirely on changing the zoning code to entice private development – with results that can fall short of the big promises. And the housing that does get built is often out of reach for the working class who need it the most.

As Mayor, Zohran will put our public dollars to work and triple the City’s production of permanently affordable, union-built, rent-stabilized homes – constructing 200,000 new units over the next 10 years. Any 100% affordable development gets fast-tracked: no more pointless delays. And Zohran will fully staff our City’s housing agencies so we can actually get the work done.

No, NYC has not made a serious effort on “changing the zoning code to entice private development”. Here’s a Brookings article talking about the problem in 2022, and attempts to solve it. These seem to have turned into the “City of Yes for Housing Opportunity” zoning text amendment adopted back in December of last year, enabling the creation of (drumroll)… an extra 82,000 homes over the next 15 years, or about 5,466 per year. Zohran’s plan, meanwhile, involves an extra 20,000/year.

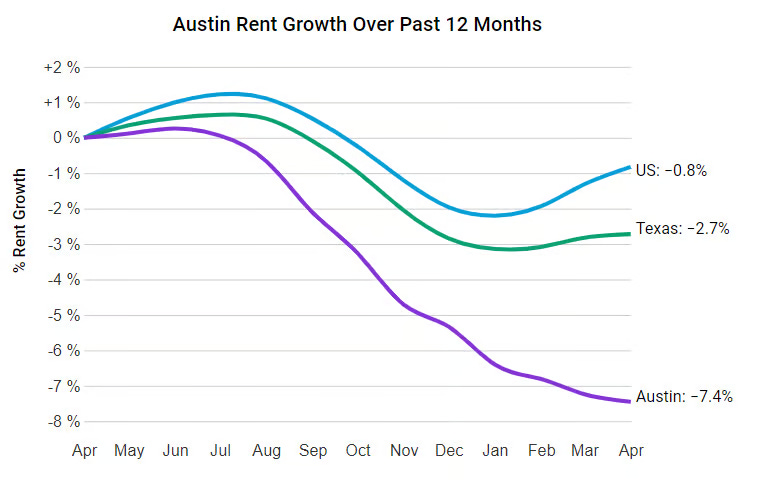

This sounds good! But these proposals are both talking about thousands of extra units in one of the biggest cities in the world, with 8.258 million people living there. Here’s an article about Austin, a city of one million, being expected to build over 20k units last year. Unsurprisingly, Austin has also been a shining star for affordability:

Austin has also seen its rents fall 22% since their peak in August 2023. If you wanted to match Austinite levels of housing development, you’d need 100k units/year, not 20k!

More annoying than the lies and the itsy-bitsy housing construction proposal is the idea that housing is made affordable by building the right type of housing. In a market as desirable and with supply as constrained as it is in New York City, the first person in line to get the next unit of housing is generally going to be wealthy. That’s why rents there are as high as they are.

To simplify the model of supply and demand, imagine a sequence of sales. The first extra unit we make goes to someone making $200k, because they could pay the most. We build just one extra unit each year, and each year, the extra unit goes to someone making $200k. If we build even more, of course the next extra unit is going to go to someone making $195k, making it seem like extra housing construction just goes to the wealthy. Then we build even more and sell to someone making $190k, then $185k, and so on. Before you can really make housing affordable, you have to clear away demand from the wealthiest potential occupants. That’s what Austin, Minneapolis, and Auckland have done, and it works!

There are other measures you can take to try to sell these extra units to the working class, as Mamdani is intent on doing. These are way worse.

For fuck’s sake, please stop doing price controls

Mamdani’s plan for New York City includes a rent freeze, meaning he’d fix the rent paid by the approximately 2 million tenants currently living in rent-stabilized apartments. The current mayor, Eric Adams, actually appointed a board that increased rents for these tenants.

Every single time that I hear about price controls like this, this image flashes in my mind like my brain is desperately reaching out for sanity as I get lobotomized:

At the point where the price ceiling hits the demand curve, the total quantity greatly exceeds the quantity suppliers are willing to provide at that price. This means a price ceiling creates an artificial shortage of a good.

Usually, rent control policies are designed to try to escape this problem, but they always suffer from the exact same supply problem in different forms. In this case, we try to avoid the supply problem by only applying a rent freeze to pre-existing rent-stabilized units. The problem with doing this is that future suppliers are not retarded. They know that these exact same policies would likely be applied to anything they build at some point in the future, and the more they observe policies like this getting enacted, the more they expect this to happen. To deal with the cost, they’ll either raise their own rents or opt not to build anything at all. If you want to lower rents for everyone, you need to be able to credibly promise to suppliers that they’ll get a return on their investment.

Maybe you can escape from this problem by making the city wholly dependent on government-built housing. I haven’t done much research on the empirical consequences of public development, so I can’t say much. I’ll just conclude by saying that if you want affordable housing, you need somebody who’s motivated to provide it just as much as you need someone who’s able to afford it. And as I’ve talked about before, the people who need rents to fall in New York City the most are not New Yorkers but poorer people living outside the city, who’d benefit greatly from the urban wage premium. Making housing cheaper for people already living there is nice, but it completely ignores the signal that the rent sends: housing is scarce and people need more.

You might wonder whether New York City is even capable of building that much more housing, since the city is already very dense. First, I don’t think that’s for us to decide. If someone owns residential land in New York City and an army of potential apartment-dwellers would gladly pay them if they redeveloped it, they should have the freedom to build as densely as they like, within reasonable safety standards, of course. Second, NYC could absolutely be more dense: Manhattan has a much higher population density than the city as a whole, but is still a great place to live. It presents the best model for how the whole city could get denser while still being awesome.

Let’s take a look at another price control Mamdani likes: the minimum wage. This subject has been done to death by both me and other bloggers, so I’ll just include a link to Economics Is a Science, where it’s touched on. The short of it is that the minimum wage seems like it should always reduce employment, but it very often has a tiny effect, even if it’s generally negative.

Mamdani wants the NYC minimum wage of $16.50/hour to rise to $30/hour by 2030. Because inflation will inevitably raise the average price level for both labor and goods, this is comparable to imposing a $27/hour minimum wage today (assuming a 2% rate of inflation each year), about 63% higher than the status quo. Such a minimum wage would clearly be binding1 on a very large number of workers. At $27/hour, working full-time, you would make about $56,160 a year. About 31% of households in New York City make less than this!

If we want these people to continue to be employed, it has to be profitable for firms to employ them even at the new minimum wage. Otherwise, they’ll just get laid off.2 If we assume that won’t happen, we’re assuming a completely absurd degree of exploitation, with people making $21/hour at Arby’s getting underpaid by something like 25%. Competition for labor in a place like New York City is intense, with massively productive firms competing in a dense environment with literally hundreds of thousands of others. If they were getting underpaid that much, it would be a huge opportunity for other firms to profit by paying those workers more to come join them. They wouldn’t even have to pay them the full value of their labor to attract them. I don’t think the near-zero employment effects we’ve seen elsewhere would replicate in this case.

As for the “no billionaires” idea, he’s being ridiculous.3 Obviously, he doesn’t mean he wants to physically erase billionaires from existence, and instead, we might tax them and spend that money on public services. I’d like to see that happen. But clearly there’s an optimal amount of taxation, since taking away everything they own would cause them to flee the country. Michael Bloomberg, a resident of New York City, has over $100 billion in wealth. If you taxed that wealth to make him a millionaire, you would be taxing his wealth at a rate of over 99%. That is obviously not revenue-maximizing! If we were talking about income taxation, estimates of the revenue-maximizing average rate are between 30% and 70%, so this kind of wealth tax sounds completely implausible.

Now, maybe you’d then counter that the idea is to eliminate the systemic features that lead to the existence of billionaires, since without exploitation, they couldn’t exist. This is also ridiculous. The status of “billionaire” usually arises from owning a very valuable company (which might be so valuable because it’s exploitative, as claimed). For example, Bloomberg owns an 88% stake in Bloomberg LP, the finance-focused media company. We’ve already done work on the effect of minimum wage hikes on the valuation of companies, and (1) these effects exist but are not large enough to erase every billionaire, and (2) part of our identification strategy in the linked paper is the fact that not every company has a lot of minimum wage workers!

I don’t think billionaires deserve their money in a moral sense, and in general, I think it’s ridiculous to talk about people deserving their money. If you happened to be born in Haiti, even with the same skills, you would be making a tenth of what you make in the United States. While people generally gain more money for doing good things, in a more static sense (i.e., looking at whatever amount people have at any given point in time), it’s silly to think there’s any connection between deservingness and the amount of money someone has. If you’re living in the developed world, you have money because you were born here, and that wasn’t a choice.

On the bright side, Mamdani is proposing a 2% flat tax on incomes above $1 million, so it’s not like his actual policies are particularly reflective of a desire to have no billionaires.

Publicly-owned grocery stores

What are we doing here, man?

Grocery stores have among the lowest margins of any business in America: they generally make 1-2% in profit after tax (see chart).

That’s from The Economist’s take on this issue. If you made groceries substantially cheaper by making these stores publicly owned, you’d only keep them open by giving them lots of government money. As they describe in the article, even if you’re doing this by using government-owned land and dropping the property taxes, you’re still effectively subsidizing the store with government money, in the same way that cutting someone’s taxes is no different from giving them money.

And if this sounded bad already:

Worse, private supermarkets could get run out of business, since even squeezing their margins to zero wouldn’t be enough to rival a competitor that doesn’t pay rent. Boxing them out would erode choice, and stymie future grocery-store innovations that could transform New Yorkers’ palates—as Trader Joe’s frozen scallion pancakes and the endlessly evolving sandwich menus of the city’s bodegas already have.

But hey, who needs Trader Joe’s anyway?

Optimistically, these stores wouldn’t run competitors out of business, wouldn’t eat up tax revenues like a rabbit let loose in a garden, and wouldn’t be mismanaged. They’d solve the problem of food deserts in New York City, as Mamdani says he wants to. Is that actually a problem? Here’s Alex Tabarrok on whether these things even exist:

Here is the abstract to The Geography of Poverty and Nutrition: Food Deserts and Food Choices Across the United States (free version) by Allcott, Diamond, and Dubé:

> […] Using a structural demand model, we find that exposing low-income households to the same food availability and prices experienced by high-income households would reduce nutritional inequality by only 9%, while the remaining 91% is driven by differences in demand. […][Back to Tabarrok, skipping a bit] Even in food deserts it’s actually not that difficult to get healthy food and, contrary to popular belief, healthy food is not especially expensive. Try an Asian supermarket for plenty of cheap produce. Indeed, in any part of the United States you can find plenty of poor-people [sic] eating healthy foods and plenty of rich people eating unhealthy foods.

If you want to improve the eating habits of the poorest Americans, you should either make the healthy options much cheaper with a subsidy or make the unhealthy options much more expensive. While it’s not clear to me whether sugar is actually driving obesity, we do know that taxes on sugar-sweetened drinks cause people to buy them less, so it’s not like this kind of policy doesn’t work.4

Everything else and the best-case scenario

Mamdani seems like a cool guy with great public speaking skills and a terrible platform. He’s not going to execute New Yorkers with assault rifles, but he will very likely do next to nothing to confront the scarcity of housing in New York City, and might even render some New Yorkers unemployed.

Bad as the ideas are, he does take a liking to the abundance movement and wants to create the kind of legal environment where government action works without being horrifically expensive and slow. This is a little counterintuitive, since his platform signals that he doesn’t think making private development easier is a good idea, but that’s part and parcel of the ideas he’s endorsing here.

It’s not good to talk about Mamdani in a vacuum. Eric Adams is the next most likely winner, and his “City of Yes” was a nothingburger, dwarfed even by Mamdani’s proposed construction target. He’s also plagued by scandal, having been indicted by the federal government for conspiracy to defraud the US, wire fraud, soliciting campaign contributions from foreign nationals, and soliciting and accepting a bribe. I’d vote for Mamdani, despite everything.

Whoever wins the mayoral race, whether Adams or Mamdani, I hope they start talking about one million units in the next ten years, as proposed by Zellnor Myrie when he was still in the race, not a meager 200k. I also hope they endorse a wage subsidy for the lowest earners instead of a $30/hour minimum wage by 2030, but this is wishful thinking. Ironically, Trump provides some glimmers of hope here: as I expected, he has indeed not been effective at deporting the ten million-plus undocumented immigrants living in the US,5 and while he briefly imposed large tariffs back in April, he has since rolled much of them back. We can perhaps hope that Mamdani will temporarily raise the minimum wage only to cut it if the city implodes.6

i.e., would exceed their current wage, thus forcing their employer to either raise their wage or lay them off.

There might be cases where a firm continues to hire someone at $27/hour even though they don’t contribute that much because it’s still more profitable than searching for another worker. This is especially likely because the minimum wage tends to tick up slowly, so they can always just wait until it’s been eroded by inflation enough to make that worker profitable again.

The snippet where he talks about this is here:

He doesn’t really say anything about how to go about getting rid of billionaires, beyond saying they shouldn’t exist.

Shocking!

Current figures for deportations are in the tens of thousands. At the current pace, not even one million deportations would occur by the end of Trump’s term in January 2029.

I’m only at 66% confidence that such a minimum wage would have large (> 3% less employment compared to the counterfactual) disemployment effects.

> Maybe you can escape from this problem by making the city wholly dependent on government-built housing.

This seems to be what Singapore did, and it worked. The vast majority of citizens live in HDB (public, government-built) housing and they seem to be managing the affordability problem better than most other “top” world cities.

However, it’s clearly not a 1-1 comparison because Singapore’s government has unusually high levels of state capacity, much greater than that of NYC’s government. It is also sovereign, so it can muster far more tax revenue on its own without adding onto state and federal tax burdens.

"In this case, we try to avoid the supply problem by only applying a rent freeze to pre-existing rent-stabilized units. The problem with doing this is that future suppliers are not retarded. They know that these exact same policies would likely be applied to anything they build at some point in the future, and the more they observe policies like this getting enacted, the more they expect this to happen. To deal with the cost, they’ll either raise their own rents or opt not to build anything at all."

A few comments on this -1) there really has not been a ratchet of more apartments getting swept into price controls. The last apartments involuntarily placed into rent stabilization were built in 1973 and there has not been any expansion in the last 50 years. 2) Landlords/developers do not raise rents to pass on additional costs. They charge as much as they can regardless of costs. Landlords are greedy! They don't just try to cover their costs. 3) Developers are still building as much as they are legally allowed in almost all cases. The limits are usually zoning or the availability of new sites. There just aren't any examples of developers building anything less than the maximum legally allowed by zoning because of rent control.

I say this as a long time hardcore Build More Housing YIMBY. We need more housing and we need it almost any way we can get it. YIMBYism is gaining popularity, but it is still something the majority of the electorate is deeply suspiscious of, and we need to be practical about expanding the tent. I think the knee jerk Econ 101 opposition to rent control is cutting off a lot of potential allies and compromises and deals we could make with the left. I would be happy to trade some form of expanded rent regulation for other pro-housing initiatives (zoning, historical preservation, local reviews) that I think are more important bottlenecks to new supply.