Consider the cultural value of cancer. Cancer patients have created books like A Survivor’s Guide to Kicking Cancer’s Ass and The Cancer Journals. They’ve created new language to describe their lives: cancer is an enemy to be defeated, and finishing treatment means “beating” cancer just as much as surviving it. People dealing with cancer have their own social groups and support networks built around their disease, like the Cancer Support Community. Even if cancer causes them to suffer at times, it also brings them together in a way that nothing else does.

Cancer survivors have produced great works of visual art, too. After losing her breasts to cancer, artist Matuschka created one of the most powerful images ever featured on the cover of the New York Times. And Henri Matisse, having survived surgery for his duodenal cancer, created an entirely new artform while confined to his bed. This form was used in his “cut-outs” series, now featured in the MoMA.

Many claim that it’s important that we prevent cancer before it happens. Because many forms of cancer are genetic, this can be done through embryo selection, the practice of fertilizing multiple human embryos and letting the parents choose one to implant. While it’s clear where they’re coming from, perhaps it’s morally permissible to select for cancer, rather than against it.

If cancer survivors produce such great works of art, it may be preferable that they exist. Matisse and Matuschka are only two examples among lots of great artists: Hannah Wilke, Jo Spence, Audre Lord, and many more. It can also be argued that the suffering cancer produces is part of what makes happiness possible, since it forms a contrast against the otherwise mundane feeling of being alive, unencumbered by struggle. Viktor Frankl, a philosopher and psychologist, believed suffering can allow you to find meaning in life, having seen this in the experiences he documented in Man’s Search for Meaning, a chronicle of his experiences during the Holocaust.

You might argue that it’s wrong to choose to give someone cancer. But notice that for an embryo that is likely to develop cancer, the alternative to being selected for gestation and birth is non-existence. This is Derek Parfit’s non-identity problem. With this in mind, it seems that you can’t harm someone by selecting their embryo, even if they have a cancer-causing gene. “Why would you give your child cancer?” is a nonsensical question when they wouldn’t have been born otherwise.

Less obvious is that a cancer-surviving parent may form a stronger bond with their child if they develop cancer at some point. An extreme case might make this more obvious: suppose that we eradicate all natural forms of death entirely, in particular heart disease, cancer, and stroke. Newer generations would exist in a world alien to that of their forebears, and it may prove difficult for them to understand and connect with their mortally-challenged parents.

What I Said Is Nonsense

Ludwig Wittgenstein used his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus to, in part, explain how language represents the world. Troublingly, he did so by using language, which shouldn’t be logically possible.1 He thus concluded that “Anyone who understands me eventually recognizes [my propositions] as nonsensical, when he has used them—as steps—to climb up beyond them.”

While the analogues are imperfect, the arguments I’ve just presented are taken from Jacqueline Mae Wallis’s “Is it ever morally permissible to select for deafness in one’s child?”, which argues that it is sometimes morally permissible. She argues that it’s valuable for deaf people to exist, deploys Parfit’s non-identity problem to argue the deaf child isn’t harmed by the selection process, and borrows an argument from Robert Sparrow’s “Better off Deaf?” by claiming deaf parents are better equipped to raise deaf children than hearing children. That argument is the least analogous, since it’s easy to see how deaf parents are better able to raise deaf children, but not so easy to see how cancer survivors are better at raising future cancer patients.

But the greatest difference in analogy is this: people form identities around deafness but don’t do the same for surviving cancer. There is no language built around having cancer and not, where survivors are referred to with some capitalized word like “Cancerites” and people who’ve never had the disease are referred to as “Noncans”. Some deaf people and advocates spell the word as Deaf, perhaps to emphasize the distinctness of their identity or to emphasize that they’re important, even if they’re often ignored. Because these identities exist, the thought of peacefully removing deaf people from the world through embryo selection, genetic modification, or some kind of cure, appears harmful to the deaf and to advocates.

I suspect that it’s because this sense of identity is so powerful that, as in Wallis’s paper, some deaf people deny the concept of disability entirely:

Because many Deaf advocates define deafness without using a deficit or dysfunction model, and because their evaluation arises from the lived experiences of Deaf people, the next step might be to deny entirely, as evident in the quotation above, the “disability” label.

With cancer, I could deploy the same ideas used in the article, talking about how we all exist on a spectrum of functioning and having cancer is just one part of that spectrum. But you’ll never see someone with cancer denying the concept of disease. Deafness seems to have developed into a distinct identity because, unlike cancer, it permanently changes the way you experience the world in a big way, and creates an entirely new in-group of other deaf people you can communicate with through a distinct language. Tribalistic instincts seem inevitable here, and when activists perceive a persecuted or disadvantaged tribe, they’ll come up with rationalizations to defend it, even if that tribe is formed around a disability. So while it’s easy to see the absurdity in selecting for cancer, it somehow feels reasonable to select for deafness.

I wish I had more to say on this point, but I’m really uncertain about when the existence of an identity group is and isn’t good on net. It’s also not clear how easily we can eliminate a sense of identity and bring people into a larger group they should be a part of. This isn’t the main point anyway.

The point of reusing Wallis’s arguments to argue that it’s morally permissible to select for cancer is, of course, to try to defeat those arguments and build some intuition against them. The non-identity problem (recall that this refers to how a child that otherwise wouldn’t exist isn’t harmed by being born deaf), despite being drawn from a great philosopher, forms a particularly bad argument in this case.2 Consider a typical soon-to-be mother with ten embryos to choose from. She’s definitely not interested in having ten children, so she’ll only choose two of them. This tells us that regardless of what choice she makes, eight embryos will never develop into children. In other words, eight children are condemned to non-existence no matter what decision is made. When Wallis and others point to how a deaf child isn’t harmed by being selected to be born, they’re pointing to something that was never relevant to the decision to begin with: eight unborn embryos are a sunk cost. Certainly, if one of her opponents were arguing that the deaf child is the one who is harmed by the choice to select them, this would be a good point to make. But I don’t think that’s a typical position to take, or one worth attacking.

Wallis spends some time defending the idea that deaf people are valuable enough that they should exist. I think she gave a weak argument. If it were true, we would expect some people to choose to be deaf, or for some people to encourage others to choose deafness, even if non-permanently. There aren’t many cases of this happening, of course, but I did find one in “A Compelling Desire for Deafness” (2006) by David Veale. Here’s the abstract:

A case is described of a patient who has a compelling and persistent desire to become deaf. She often kept cotton wool moistened with oil in her ears and was learning sign language. Living without sound appeared to be a severe form of avoidance behavior from hyperacusis [a disorder that makes everyday noises unbearably loud] and misophonia [a similar disorder, triggered by specific sounds, e.g. pen clicking]. She had a borderline personality disorder that was associated with a poor sense of self. Her desire to be deaf may be one aspect of gaining an identity for herself and to compensate for feeling like an alien and gaining acceptance in the Deaf community. Will a compelling desire for deafness ever become a recognized mental disorder one day for which hearing patients may be offered elective deafness after a period of assessment and living like a deaf person? Those working in the field of deafness should be aware that individuals may occasionally be seeking elective deafness or self-inflicting deafness to obtain a hearing aid.

This patient, unfortunately, was interested in being deaf because she was mentally ill, not because she thought she’d become the next Kitty O’Neill, who Wallis points to as an example of somehow who believed themself to be enhanced by their deafness. I’m not willing to dismiss this desire outright as mental illness, since mental illness is, after all, merely the state of having a weird brain. Wallis and I can agree on that point. But the fact that the typical person’s preferences are so strongly against choosing deafness suggests that it isn’t as beneficial as Wallis claims. There are no selfless types choosing to be deaf to fill the world with its benefits, and there’s an extreme shortage of advocacy for more deaf people. (Maybe the naturally-occurring number is socially optimal, somehow? That seems implausible, and Wallis herself seems to be implying that there’s a shortage.)

The economic impact of deafness—you didn’t think I’d skimp out on economics, did you?—is very negative. There are obvious theoretical reasons to believe this, since being deaf in many ways limits your choice of occupation and your ability to perform well on the job. There are huge numbers of jobs where being deaf either guarantees you can’t do it or severely diminishes your capabilities: musician, doctor, firefighter, cashier, receptionist, military servicemember, customer support technician, and many more. I’m surprised by how willing Wallis was to brush off the full range of opportunities eliminated or constrained by being deaf, instead preferring to only mention becoming a musician, as if that provides a complete account. Note that the deaf can often read lips, so being a cashier isn’t out of the question; it’s just harder.

Empirically, we can rely on William A. Welsh’s “The Economic Impact of Deafness”. In his sample of 4,398 deaf adults, provided by the IRS, deaf people were less likely to go to college, and “Over the course of a lifetime deaf people earn between $356,000 and $609,000 less than their comparably educated hearing counterparts.” This is a very large impact, since median lifetime earnings in the US were ~$1.7 million in 2023. It’s also consistent with our theoretical suspicion (should we even call it a “suspicion”?) that deaf people are less capable in many roles.

Here it’s important to note that this is bad for people who aren’t deaf, too. Working benefits customers and employers, and so the lifetime loss of hundreds of thousands of dollars experienced by these deaf individuals is not a loss to only them. If more deaf people are born in place of hearing people, everyone else is worse off, too—even some deaf people, who would also receive fewer goods and services from people in those jobs I mentioned.

I think it’s obviously incorrect that the expected happiness experienced by a potential deaf person is equal to that of a hearing person, but even if it was, I don’t think the case for selecting for deafness would be strong. If I had to, for the sake of a thought experiment, I would tell you to imagine a disability that makes you harder to take care of but also happier than the typical person. I actually don’t have to do that because Down syndrome (DS) exists in real life. If parents merely wanted their children to be happy, they would all be hoping for their kid to have DS. Here’s a piece of the abstract of “Self-perceptions from People with Down Syndrome”:

Among those surveyed, nearly 99% of people with Down syndrome indicated that they were happy with their lives; 97% liked who they are; and 96% liked how they look. Nearly 99% people with Down syndrome expressed love for their families, and 97% liked their brothers and sisters.

For some reason3 Google’s AI will say “No, people with Down syndrome are not generally or automatically happier than anyone else” when you look up whether people with DS are generally happier, but this seems like pretty solid evidence. You might think the real problem is for the parents, but the added medical expenses were, in one study of 5,000+ individuals with DS, a surprisingly low ~$84/month for the first 18 years of life. I don’t think the utilitarian case for more people with DS would be easy to make, but it seems like you could make a strong argument if you gave it a solid effort. The trouble is that, as quickly revealed by thinking about Nozick’s experience machine, we don’t actually value being happy as the end-all-be-all of existence. All of this is to say that even if deaf people would be just as happy in the counterfactual case where they aren’t deaf, I don’t think that would imply it’s morally permissible to select for deafness. People generally don’t think it’s wise to select for DS.

So far I’ve focused on the economic implications of selecting for a disability, and the implications for their personal happiness, but we should also be thinking about the cultural value of the disabled. Interestingly, while Wallis spends some time arguing that deaf people may have enhanced visual capabilities, there are very few examples of famous visual artists who were deaf. Deaf people are rare enough that we should expect there to be few, but if you look up “famous deaf painters” you’re going to get a bunch of people you’ve never heard of, and you won’t feel particularly impressed by what you see in the images tab if you aren’t an art historian or snob.

There are a couple more problems I have with this positive sentiment toward “deaf culture”. First, it’s not clear that the expected cultural value of a deaf person exceeds that of a hearing person, and in fact it seems clearly lower.4 There might be people for whom deaf art is really valuable, but for each person like that there are probably a lot more who would prefer a higher probability of more Jay-Zs and Michael Jacksons. The second problem is status quo bias. If it’s good to have deaf people around for their culture, why not select for more people who can’t feel physical touch to see what kind of culture they create? How about people with hemifield neglect, whose brains are damaged such that they are physically incapable of conceiving of the portion of their view that is missing from their vision?

I think producing more artists with hemifield neglect would be even more valuable than producing more deaf artists, since this is a fascinating disorder to have. We can pack a university full of deaf people, but there’s a genuine shortage of hemifield neglect, with far too few of them to generate a Picasso or Van Gogh. We seem to be biased toward selecting for deafness and other disabilities we can already observe, even though there seems to be a strong theoretical basis on which we can guess someone would be better at what they do if they weren’t deaf—physically it only takes one capability away, even if deaf patients often develop strong talents in other areas, seemingly as a consequence of being forced to focus on things like physical touch.

Wallis also speculates that there may be some concepts that can only be communicated through sign languages, so perhaps there’s something of value that could be lost if there were no more deaf people. Even if this were the case, I don’t see how this benefits anyone except the deaf people who are capable of communicating these mysterious concepts. If it can’t be communicated to hearing people, it can’t have value to them either. I’m also very skeptical about the existence of things like this. The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is rather similar, since it suggests language shapes mental capabilities, but John Quijada never became a famous philosopher or scientist after inventing Ithkuil, an incredibly dense and precise constructed language.

Let me get to the point we seem to be nearing, except I’m going to put it in a made-up quote to signal that I don’t really agree with it.

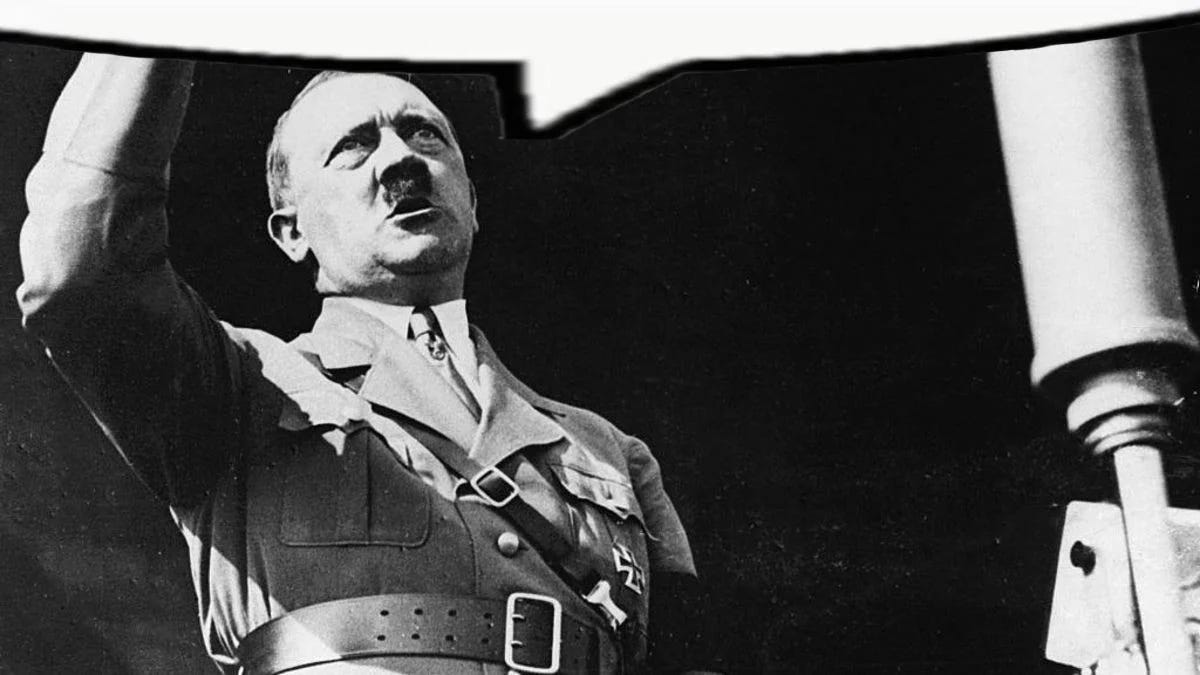

There is no need for disabled people to exist. Clearly, it would be better if they didn’t. When a disabled person exists in place of a healthy one, the productive capacity of society is diminished. A society of disabled people cannot build the Sistine Chapel. It cannot conquer continents, it cannot leave this Earth for the moon and beyond. When the sun sets on an empire of filth, there is no monument to its greatness.

I have kindness in my heart, but it is a pure love for the people of my country. The disabled take benefits from their government, their people, yet many are incapable of giving anything in return. We must eradicate the very concept of “disability” and leave room only for a strong, healthy society.

I think we can come to a sensible conclusion here without agreeing with Hitler. Yes, monuments, culture, and strength matter. People like these things. But if you ask the government to intervene and eradicate genetic disorders through mandatory embryo selection and, eventually, genetic modification, you’re asking for the existence of a government agency, run by political appointees, that decides what kinds of genes are fine and which are erbkrank. Democrats, think of what it would be like to have Robert F. Kennedy decide which genes are okay. Republicans, imagine a Democrat telling you it’s necessary to abort your child because they’re diseased.

Now return to reality for a moment. The truth is, slippery slopes like the one we’re imagining right now rarely come to fruition. The US government created an agency charged with deciding who’s allowed into an airport, and while the TSA does suck really hard and I wish it got hit by the DOGE cuts, they haven’t abused their power on a large or impactful scale (I’m sure there are smaller incidents). The FDA regulates food, but it was never captured by a radical vegan who immediately banned meat. There are problems, but no “the new genetics head just decided blue eyes are mandatory and it’s illegal to be black” problems.

I don’t think the costs of deliberately creating more disabled people are high enough for us to explicitly condemn it as immoral. If deaf parents think their child would be raised better if they were also deaf, I think they’re better prepared to make that decision than any government agency would be in practice. But I also think it’s generally the wrong choice and should be avoided. It seems clearly preferable to give your hearing child something like a reverse hearing aid and raise them deaf until they’re ready to decide whether they want to hear or not.

Before finishing, I also want to mention that a love of strength, while vaguely Hitlerite sounding, is good. Societies have tended to naturally generate social hierarchies where the most competent rise to the top, and this happens even in societies with strong rule of law because, at the end of the day, Jeff Bezos is better at running a business than most people with Down syndrome would be, and people love getting stuff from his company. We also feel a natural obligation to weaker people, and often, it seems people like Wallis and others have decided to take up ideas like “diversity is strength” precisely out of this sense of obligation and fairness.

Let me regale you with a story. When I was in 6th grade, my parents forced me to join the cross country team. I didn’t enjoy this at all, and in fact I was so embarrassed by my weakness that I would often walk away from the main gathering place under the pavilion, and I would cry. Our human instincts toward ideas about weakness seem so strong that I naturally redeveloped the same ideas you can see anywhere else, as a coping mechanism: the best runners weren’t the people coming in first or second, but were instead whoever gave it their fullest effort. Because the severely overweight girl who always came in last but ran anyway was clearly giving more effort than anyone else, I considered her to be the very best, and thought of myself more positively only because I knew I was trying.

One problem with thinking this way is that, in practice, I used it as an excuse for not truly trying to reach the top. In my mind the hierarchy was fairly fixed and all I could do was try to dampen my sense of envy. The bigger problem is shared with the slave morality Nietzsche wrote about: believing that being the best isn’t really being the best will lead to self-hatred when you find strength in yourself. If it’s good to be a meek Christian, it’s embarrassing to take first place. And so, years later when I was running a 5k with my family, I ran ahead of someone right before the very end of the race, and instead of feeling proud, I somehow felt embarrassed. I thought only of how it feels to be the loser and lost any joy I might have felt from getting ahead.

If you fixate on the importance of fairness and empathy, you might lose the joys of your own strength. A society that lifts up forms of weakness like deafness might face the same fate. We seem to be so stuck on this sense of fairness that the obvious statement “My child would be better at a lot of things if they weren’t disabled” somehow feels wrong. On a larger scale, raising people to believe that strength doesn’t matter and all forms of diversity are good seems to inevitably create weak people who won’t accomplish as much as they otherwise would have been able to.

So to restate the otherwise-Hitlerite conclusion, there is no need for disabled people to exist, but they probably always will, and we do have an obligation to help them. It’s not right for people to suffer just because of the unchosen conditions of their birth. It’s also not right to deliberately create more people who are more likely to suffer for that reason, especially when you have the option of giving them a choice, like with a reverse hearing aid. I wouldn’t say a parent’s obligations to society are infinite, but it’s always worth considering the fact that your child is less likely to do something really good for the world if you willingly select for a disability, even if it’s technically possible. If you care at all about the things society is able to produce for itself, that should have some influence on your choice of child, if you get to make one.

This feels like a Philomena Cunk bit.

Parfit didn’t create this idea to make Wallis’s argument, anyway.

woke AI, which I largely approve of

I’m calling on the concept of expected value here, which should be fairly intuitive. If you have a random variable of any kind, something that might take on many different values like 1, 0.02, or 2 million, the expected value of that variable is essentially its average. The expected value of a coinflip that can land heads (1) or tails (0) is 0.5. Multiply the possibilities by their frequency and sum them to get the expected value: 1*0.5 + 0*0.5 = 0.5. This can be used to characterize all sorts of things, and seems to have a conceptual analogue even in the cases of things that don’t appear cleanly measurable.