Imagine this.

There’s a (disorder? neurodivergency?) that children and adults alike sometimes acquire, which we’ll call ETR. It causes some peculiar behaviors, but worst of all it heightens one’s risk of suicide. People with ETR often face discrimination and have difficulty finding acceptance among others. Typically, ETR lasts for one’s whole life, but some people eventually stop showing symptoms.

Doctors have devised various treatment methods for ETR. Sometimes it’s better addressed early in life, so some children are given intensive treatments for it that are only partially reversible. (Sorry, did I say only partially reversible? I meant that we don’t really know the degree to which they’re reversible and it’s all a lot of speculation. And the study population is so small that you might as well be asking whether drinking a quarter teaspoon of gasoline on your 13th birthday has irreversible effects.) As adults, people with ETR can get even more intensive surgery to treat it. All of these treatments have high rates of success and low rates of regret among recipients. (We think? We don’t really know.) Much of the treatment for ETR is essentially acceptance—letting the patient behave differently without punishing them for it, giving them weird looks, and especially not recording them to make fun of them on the internet.

Some parents stubbornly refuse to admit their child has ETR, insisting that they’re “normal,” and refuse to let them get treated, to the dismay of doctors. Others insist that their child is one of the few who will stop showing symptoms. They force them to behave normally.

But at the end of the day, it’s all handled. Parents work with doctors to decide on the best line of treatment, and a lot of people are helped. Doctors keep doing research into ETR to understand it better and find new ways to treat it. Some of them have attachments to whatever ETR scientific paradigm they’ve chosen, but in the long run, we all live happily ever after…

…except that’s not what’s happening, because everything I just wrote characterizes transgender people.

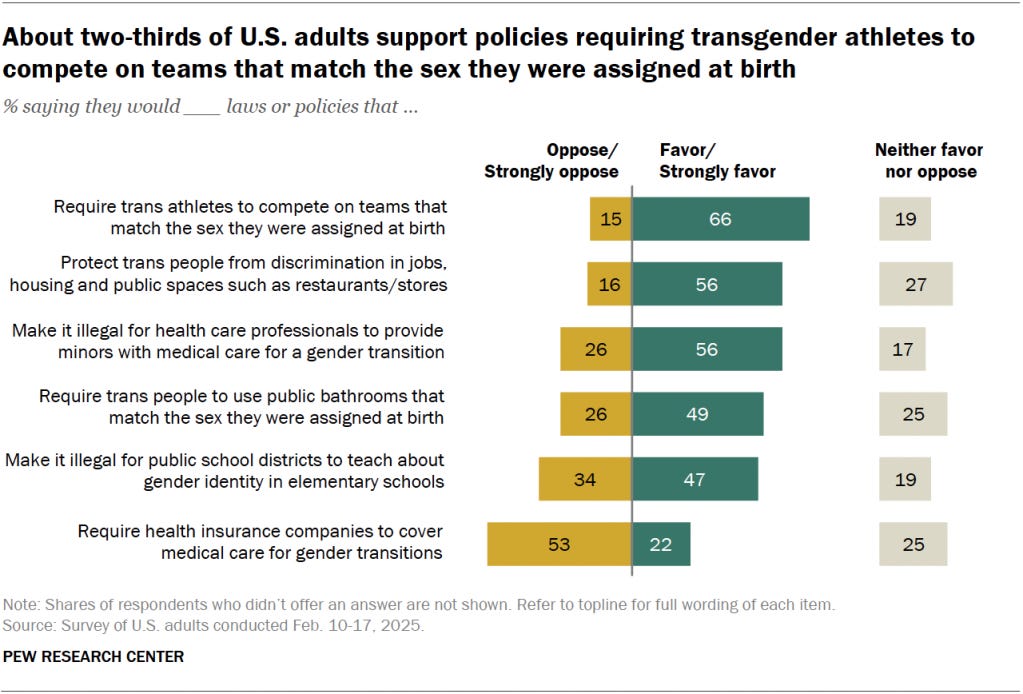

Some areas of transgender politics aren’t particularly controversial. Americans prefer that trans people be protected from discrimination by a large margin, but they also overwhelmingly want trans women to be banned from women’s sports teams.

They also prefer that it be illegal for “health care professionals to provide minors with medical care for a gender transition” by 30 points, 56% to 26%, with 17% undecided. There’s an obvious conclusion you can arrive at to get to this position, which is “How can a minor possibly be able to consent to something like that at that point in their life?” But I think one ought to see the bigger picture when considering what laws should be passed. There are really three options:

Ban minors from getting medical care for a gender transition. If this is done, there will be transgender adults talking about how much they’ve suffered because they weren’t allowed to access this care.

Allow minors to get medical care for a gender transition. If this is done, there will be some number of adults who detransitioned and wish they hadn’t been allowed to make that decision.

Something in-between. Mistakes would be made, but we would try to minimize the cases resulting from both (1) and (2).

There are no solutions to this problem that work 100% of the time. But we can try to identify the least bad solution. On that front, we can look at whatever research is available on rates of regret, beginning with this AP report:

In updated treatment guidelines issued last year, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health said evidence of later regret is scant, but that patients should be told about the possibility during psychological counseling.

Dutch research from several years ago found no evidence of regret in transgender adults who had comprehensive psychological evaluations in childhood before undergoing puberty blockers and hormone treatment.

Some studies suggest that rates of regret have declined over the years as patient selection and treatment methods have improved. In a review of 27 studies involving almost 8,000 teens and adults who had transgender surgeries, mostly in Europe, the U.S and Canada, 1% on average expressed regret. For some, regret was temporary, but a small number went on to have detransitioning or reversal surgeries, the 2021 review said.

In contrast to the relative confidence of this AP report, we have “The Detransition Rate Is Unknown”. As the author describes, the extremely low rates of regret commonly reported are based on studies that measure the outcome early and sometimes rely on biased samples. The rate of regret might rise later in life and may be higher in an unbiased, random sample of those who received treatment. Here are a couple of examples the author offers:

Also, selecting on characteristics that cannot be measured ahead of time, e.g., regret or detransition studies including only those who continue to come to a gender clinic (Davies et al., 2019; Wiepjes et al., 2018) or those who still identify as transgender or non-binary (Turban et al., 2021) misses entire classes of regretters or detransitioners who do not fall into those categories (those who stop treatment without announcing regret to their clinic and those who no longer consider themselves transgender or non-binary, respectively).

So it seems we should be restraining our judgment of this a bit. I think that the available research should still nudge you in the direction of thinking rates of regret are low, but not by much.

I really wish I could tell you the exact share of people who were denied transgender healthcare as a minor and still wish they had received it later in life. That’s the price of the more popular option of forbidding this kind of treatment. If that rate were low, it would reflect positively on the common “it’s just a phase” narrative and the issue would be mostly settled. But all I can find is studies like this one, finding lower rates of suicidality among those who had access:

Of the sample [20,619 transgender adults ages 18 to 36], 16.9% reported that they ever wanted pubertal suppression as part of their gender-related care. Their mean age was 23.4 years, and 45.2% were assigned male sex at birth. Of them, 2.5% received pubertal suppression. After adjustment for demographic variables and level of family support for gender identity, those who received treatment with pubertal suppression, when compared with those who wanted pubertal suppression but did not receive it, had lower odds of lifetime suicidal ideation (adjusted odds ratio = 0.3; 95% confidence interval = 0.2–0.6).

There’s also a difference-in-differences study exploiting the passage of various anti-trans state laws to identify their effect on suicide risk. They looked at many kinds of laws (e.g. forbidding trans people from using the bathroom corresponding to their gender), and found that these restrictions generally raised suicide risk. But what we’re really interested in is laws limiting access to transgender healthcare. Much to my annoyance, they didn’t disaggregate by type of law. But it probably wouldn’t matter anyway because their study seems to only cover a few years after the enactment of these laws!

We will probably have to wait years for a diff-in-diff study of laws restricting access to trans healthcare as a minor that could maybe tell us whether the long-term impact is typically positive or negative. We might even get such a study, only to discover that it wasn’t well-powered enough to detect an effect if it exists.

In the meantime, this seems to be an issue where even the right tradeoff to make isn’t obvious, in addition to there being no solution that works for everyone. The difference between a kid with ETR and a transgender kid is that in one case, it’s easy to recognize the problem is hard, and in the other, most people seem to be very confident the problem has an easy solution that all the insane people need to accept. I think it should be obvious after reading this that we’re closer to the ETR scenario than the obvious one.

I would permit transgender healthcare for minors if unanimous consent is acquired between the kid, doctor, and a parent. California law is similar, though it appears that only the consent of the parent and child is required. This kind of system results in errors where treatment is unavailable when it should be,1 and available when it shouldn’t, but this is closer to minimizing errors than the outright bans enacted by Republican legislatures across the country.

Photo source: Cornell Policy Group.

When a parent refuses and the child never changes their mind about being transgender, which again, we don’t even know the frequency of.

Thank you for bringing more awareness to this important topic. I know you would agree that the highly vulnerable transgender community deserves more facts vs. fears, so well done. Too many lies and prejudices surround their community as a whole. Although every journey is a personal one, I agree the apparent lack of data as an aggregate group does nothing to help them. Love your clear writing and admire your earnest attempts to see more justice in this world.

Your argument is predicated on the clearly false notion that transgenderism is an inborn neurological condition rather than a cultural construct that spreads socially. The simple fact that you recognize this condition as a disease, coupled with an etiological understanding of the psychology of transgenderism, means that you tacitly agree that the phenomenon is destructive in and of itself.

Do you agree that it is better to NOT believe oneself to be in need of medical mutilation to feel apposite in one’s own body?