How Do You Summarize Things Objectively?

Wikipedia vs. Grokipedia on Immigration

Grokipedia has a lot of differences with Wikipedia, some of which involve things like made-up evidence for an elite child sex trafficking ring based out of a Pizzeria. There are other differences that aren’t so easy to dunk on. Here’s Wikipedia on undocumented immigration:

A number of studies have shown that illegal immigration increases the welfare of natives. A 2015 study found that “ increasing deportation rates and tightening border control weakens low-skilled labor markets, increasing unemployment of native low-skilled workers. Legalization, instead, decreases the unemployment rate of low-skilled natives and increases income per native.” A study by economist Giovanni Peri concluded that between 1990 and 2004, immigrant workers raised the wages of native born workers in general by 4%, while more recent immigrants suppressed wages of previous immigrants.

And now Grokipedia:

Empirical analyses indicate that illegal immigration, characterized by a disproportionate concentration of low-skilled workers, exerts downward pressure on wages and employment opportunities for comparable native-born workers, particularly those without high school diplomas. Undocumented immigrants often fill roles in manual labor sectors such as construction, agriculture, and food services, increasing labor supply in these segments and competing directly with native low-skilled workers who lack bargaining power or alternative options. This supply shock aligns with basic economic principles of labor demand elasticity, where an influx of substitutable workers reduces equilibrium wages unless offset by proportional demand growth.

To grant authority to these ideas, Grokipedia then goes on to cite the work of labor economist George Borjas. (Please do not become negatively polarized against Borjas if you’re a fan of immigration—he’s a great economist.) We now not only have parallel intellectual realities for the mass public to inhabit, but a website providing the same intellectual flair as Wikipedia that gives voice to one such parallel reality. Great job, team.

Now, to be fair to everyone involved: this is very hard and even the Wikipedia article referenced here kinda sucks. Should we really be providing nothing but a stellar review to the economic impact of undocumented immigration into the United States? That whole section reads like a compilation of sources selected specifically because they show undocumented immigration to be beneficial or have no meaningful impact. Grokipedia seems to be merely committing the same sin in the opposite direction, but they can’t both be right, and we shouldn’t just pick the answer in the middle.

The complexity of an issue doesn’t prevent you from analyzing it objectively. There are lots of studies of the effect of immigration on native wages and we can summarize them. But how? There doesn’t seem to be a transparently obvious way to do this. If I wanted to focus on fairness to both sides, I would do something like find every study ever done on the effect of immigration on wages and make a plot of their estimated effects. Then we could look at the average effect and say “Alright, it’s positive/neutral/negative/whatever.”

But even that doesn’t seem to solve the problem. Anyone with basic literacy can do that, and it’s been done multiple times already by smarter men than I with even better tools than “just take the average”. (As a technical note, at this point we’re looking at the effect of all immigration on wages, rather than the harder-to-detect effect of undocumented immigration. That shouldn’t matter too much as long as we can observe the skill levels and other characteristics that might differ between groups and adjust our judgment accordingly.) Here’s Giovanni Peri finding the effect is generally nil because immigrants have tended to be ~ equally low- and high-skilled.

That’s not the only summary, of course. Here are excerpts from George Borjas’s Labor Economics:

There exists a consensus in the many studies that estimate these spatial correlations.1 The spatial correlation is probably slightly negative, so the native wage is somewhat lower in those labor markets where immigrants tend to reside. But the magnitude of this correlation is often very small. The evidence thus suggests that immigrants seem not to have much of an impact on the labor market opportunities of native workers.

[after discussing the Mariel boatlift study, which found no meaningful effect on wages by comparing changes in wages in Miami to changes in similar cities unaffected by the boatlift] The conclusion that even large and unexpected immigrant flows do not seem to adversely affect local labor market conditions seems to be confirmed by the experience of other countries. For instance, 900,000 persons of European origin returned to France within one year after the independence of Algeria in 1962, increasing France’s labor force by about 2 percent. Nevertheless, there is no evidence that this increase in labor supply had a sizable impact on the affected labor markets. Similarly, when Portugal lost the African colonies of Mozambique and Angola in the mid-1970s, nearly 600,000 persons returned to Portugal, increasing Portugal’s population by almost 7 percent. The retornados did not seem to have a large impact on the Portuguese economy.

Borjas then points out a bit of an issue with the difference-in-differences approach: if you look at a case where no boatlift happened in the 1990s and apply the exact same method, you somehow find that this non-existent 1990s boatlift raised unemployment for black workers in Miami. That throws the Mariel result into question. The key assumption of any differences-in-differences study is that the two places or units being observed would have followed the same trend if not for the intervention (in this case, immigration), and it seems that this parallel trends assumption is hard to meet.

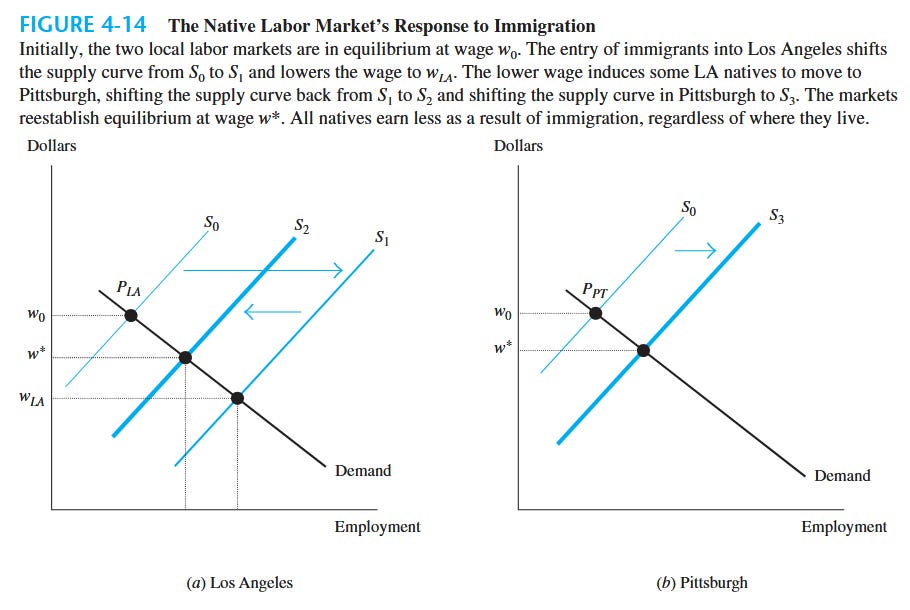

Borjas then explains that because workers in the US might migrate out of a city in response to immigrants entering the labor market, preferring the higher wages experienced elsewhere in the US, we might not be able to detect the effects of immigration on wages at the level of cities. Immigrants enter, Americans leave, and wages appear to be unaffected only because the Americans left. This turns out to be only a theoretical suspicion, since the evidence on whether this really happens is mixed. That aside, Borjas turns to a national-level approach. For each skill group of natives, we can look at how its wages changed over time and how the share of that group that was foreign-born changed over time. Skill groups whose foreign-born % rose more tended to have lower wage growth.

This may be a minor quibble, but I really don’t like how Borjas depicted the effect of natives migrating between cities in response to immigrant entrants:

A ton of new consumers enter Pittsburgh, but a labor demand shift is nowhere to be found. Borjas doesn’t stop to discuss why he makes this assumption. One of my senior-year professors considered this the econ-101 standard when I was writing a briefing paper on mass deportation, and yes, my introductory microeconomics professor also made this assumption in the context of intercity migration responding to zoning laws. I really don’t think economists make unrealistic assumptions much of the time, but this one is surprisingly common.

Before he discussed any of this, Borjas pointed out that the long-run theoretical impact of immigration on wages is nil because lower wages raise the returns to capital, which encourages more investment and ultimately higher labor productivity and wages. Grokipedia says as much. In fact, everything Grokipedia says seems like a regurgitation of the Borjas textbook, treating his national-level approach as the definitive way to identify the effect of undocumented immigration on wages.

But very strangely, as Card points out in his response to the Borjas work Grokipedia uses, the study holds capital fixed in the long run. No adjustment is assumed to be able to occur during the decades examined, despite Borjas having discussed in his textbook how important this is for wage adjustments. He also points out that the Borjas conclusion depends crucially on the assumption of perfect substitutability between immigrant and native workers, and with imperfect substitutability, natives appear to have gained, not lost, from immigration.

This all just feels overwhelming. There is a huge mess of methodological issues that are getting in the way of our ability to understand what’s going on here. Can’t we just put George Borjas and David Card in a room and ask them to come to a consensus?

Frankly, I don’t think we need to. Beneath every muck of disagreement in economics is agreement on some essential questions. To begin with, the claim Borjas defends isn’t that immigration is per se bad for the United States, or that deporting tens of millions of undocumented immigrants from the US would raise wages for natives. (Borjas himself wants a slow-down in immigration, but no additional barriers at the border, and he opposes mass deportation as “inhumane”.) Borjas has provided substantial evidence that low-skilled immigration has harmed low-skilled workers in the United States, but not that it has harmed workers in the United States in general. Even his reappraisal of the Mariel boatlift study only found a negative wage effect for high school dropouts.

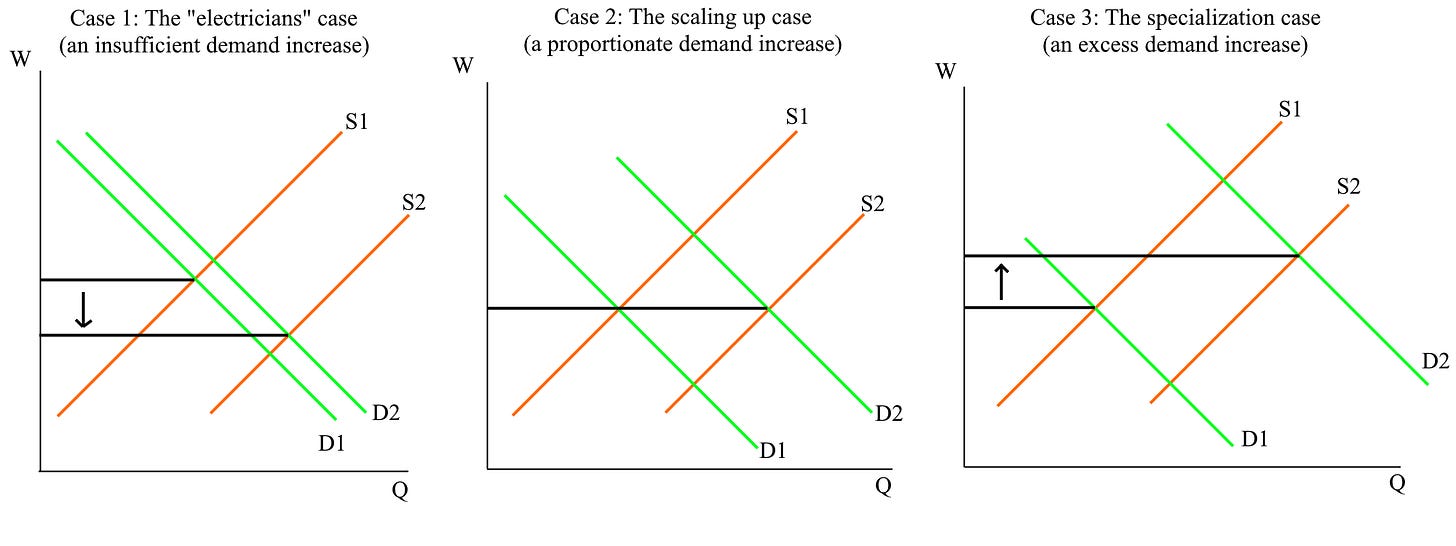

Before taking further steps to try to summarize the available evidence, it’s a good idea to take a great theoretical tool that works in many other contexts—supply and demand—and apply it here.2 For any labor market (this could be the national labor market or a smaller one like the market for electricians) there are three cases to focus on:

The immigrants don’t raise labor demand much compared to labor supply. This could happen in the market for electricians if immigrants are disproportionately likely to be electricians. These immigrants would raise the supply of electricians, but they wouldn’t be spending their money paying other electricians, so labor demand is mostly the same and wages fall.

The immigrants raise labor demand in proportion to labor supply. This could happen if they look fairly similar to the current population. If your economy has an electrician, a manager, and a few service workers and you bring in an electrician, a manager, and a few service workers, you have just “scaled up” your economy through immigration: the new service workers compete with the old ones, but that new electrician needs some place to buy a hamburger, and so do the new service workers. New jobs are created by the new demand.

The immigrants raise labor demand even more than labor supply. This can happen in a variety of ways, but the most realistic option is through complementarity: the immigrants, who may be better at manual tasks and worse at language-based ones, specialize in manual labor, while natives specialize in language-based tasks and labor productivity rises, resulting in higher labor demand and higher wages.

Here is an illustration of each case. The black lines indicate equilibrium wage levels, and the arrows indicate the direction wages move. Numbers are used to indicate the time of a curve (so “S2” is the second supply curve, after immigration has occurred).

It is my sincere wish that every discussion of the effect of immigration on wages begin with something like this. Supply and demand is a sensible tool and it works empirically. These three cases, while still simplifying, provide a reasonable explanation for why wage effects might vary. They’re more realistic than holding demand fixed and calling it a day.

The quibbles between researchers have been over whether case 1 describes how things have worked out for low-skilled workers in the US. But even if you assume that’s what has happened, as Borjas believes, the situation we’re describing is one where the electricians face a lot of extra competition while demand rises a teeny bit not just in their own market but everywhere, meaning anyone not competing with the electricians—this should be most Americans—benefits. I couldn’t find an explicit comment on this by Borjas, but I did find this transcript from 2003 where he sort of alludes to what I’m saying:

This is an argument that you often hear, especially that economists make about how these people don’t wanna take these kinds of jobs. The way it usually takes place is the following. Immigrants do jobs natives don’t wanna do. I think the correct statement is immigrants do jobs natives don’t wanna at the going wage. Let me give you a little anecdote. I used to live in California. Every person mows lawns in Southern California’s Mexican. Totally legal. Low skill and clearly leads to a lot of cheap labor for people who wanna hire, you know, people who - who - who mow lawns. And the lawns are very nice in southern California. I moved to Boston. Very few Mexicans in Boston. Nevertheless the lawns are still green. If people want - if people want those kinds of services they will pay for it. So it’s true. It is certainly true that immigrants do particular kinds of jobs but is at the expense of somebody else in some sense. Somebody’s paying for the fact that we now have an increased supply of low-wage labor and it happens to be low-wage workers.

So low-skilled, low-wage workers already in the US face lower wages while everyone else gets cheaper services. It’s reasonable to conclude that the policy of stopping the flow of undocumented immigration benefits a minority of the American population, the low-skilled, while hurting most Americans and the undocumented immigrants themselves. Given that, this would be a really strange policy to seek out even if you’re a nationalist who only cares about Americans. I do think it’s worthwhile to let the costs and benefits experienced by low-wage workers weigh more heavily on our minds, since the marginal happiness they get from money is much higher (think of how an extra $1k is pish-posh if you make $200k and awesome if you work at McDonald’s), but I don’t think any reasonable weighing of the costs and benefits here tells you to prioritize low-skilled workers in this way.

Is the evidence any less ambiguous when it comes to deportation? There are a variety of studies that come to mind immediately. We can begin with Prachi Mishra’s study of Mexican emigration, described by Borjas in Labor Economics. Here are the relevant parts of the abstract: “The main result in the paper is that emigration has a strong and positive effect on Mexican wages. […] Simple welfare calculations based on a labor demand–supply framework suggest that the aggregate welfare loss to Mexico due to emigration is small.” This seems mostly analogous to deportation. The paper also suggests the theoretical approach I just described isn’t correct: emigration appears to have raised wages for every skill level in Mexico rather than just those that shed lots of workers.

Next, there are studies looking more directly at the effects of deportation on wages and employment in the US. In East et al., the Secure Communities program is used as a natural experiment in deportation. Because the program was deployed at different times in different areas pseudo-randomly, we can compare them to see what the labor market impact is. In this case, forced emigration resulted in lower wages and employment for US-born workers.

Some additional papers on emigration:

Docquier, Ozden, and Peri (2010): Finds that emigration from European countries lowered their average wages.

Elsner (2013): Looks at the enlargement of the EU, which made free migration out of Eastern Europe easier. “[…] I find that over the period of five years emigration increased the wages of young workers by 6%, while it had no effect on the wages of old workers. Contrary to the immigration literature, there is no significant effect of emigration on the wage distribution between high-skilled and low-skilled workers.”

Mishra (2014): A literature review of the effect of emigration on wages. Finds emigration supply shocks generally raise wages.

And some more papers on deportation, or coerced emigration in general:

Clemens, Lewis & Postel (2018): Checks to see if excluding ~0.5 million Mexican farmworkers had a labor market impact, with a focus on “endogenous technical advance”, meaning the influence the Bracero exclusion had on mechanization. “We fail to reject zero labor market impact [i.e. they can’t say the exclusion did anything], inconsistent with this model.”

Lee, Peri, and Yasenov (2022): Checks if the coercing of Mexican immigrants to return to Mexico in the 1930s influenced employment for natives. “[…] we find that Mexican repatriations resulted in reduced employment and occupational downgrading for U.S. natives. These patterns were stronger for low-skilled workers and for workers in urban locations.”

Lynch and Ettlinger (2024): A literature review focusing on deportation rather than emigration. Finds deportation tends to lower wages and employment for the native-born.

If the available evidence is correct and deportation, unlike emigration, tends to lower wages for the native-born, the natural question is why. An emigrant can carefully plan when they’ll leave, while someone facing deportation or leaving for fear of it usually doesn’t have the luxury. This disruptive effect on businesses seems likely to be the main difference.

We’ve spent thousands of words on chasing this elusive objective synthesis of all the available evidence. But I don’t really mean to say “Here is the evidence, here’s how to summarize it objectively, and here’s the conclusion”. The lesson is that sometimes, the most important conclusions come from areas of agreement, not disagreement.

There’s disagreement between researchers over whether low-skilled immigrants, and in particular undocumented immigrants, harm low-skilled natives. It’s also not clear whether deportations would help—emigration evidence seems to suggest it would, but the three cases of deportation in the US thus far studied (the 1930s case, the Bracero exclusion in the 1960s, and the Secure Communities case) have not appeared to benefit natives. These are the two areas where the evidence appears least clear.

There is relatively little disagreement over whether immigration harms the native-born as a whole, rather than particular native-born subgroups. Borjas, a relatively immigration-skeptic economist, has his own 1995 paper suggesting that immigration is helpful to Americans overall, though he does find these benefits are small (on the order of $6 billion per year, ~0.08% of GDP at the time). You might also recall the Giovanni Peri paper mentioned earlier, which while disagreeing with Borjas over wages comes to the same conclusion about immigration benefiting Americans overall. The long run picture is even better, with Borjas describing in his textbook how in theory, lower wages should raise the returns to capital, increase the long-run capital stock, and thus raise wages back to their previous level. From a scientific perspective, then, the idea that immigration makes the native-born economically worse off in the long run is very likely false, and highly questionable even in the short run. If immigration is bad for the typical American, that can only be shown through effects outside the domain of economics.3

If you wish to be reminded of the surveys of economists I’ve often cited, here are some of them. Note that percentages for those who did not answer have been omitted for brevity.

Low-Skilled Immigrants (2013): “The average US citizen would be better off if a larger number of low-skilled foreign workers were legally allowed to enter the US each year.” - 52% agree, 28% uncertain, 9% disagree.

“Unless they were compensated by others, many low-skilled American workers would be substantially worse off if a larger number of low-skilled foreign workers were legally allowed to enter the US each year.” - 50% agree, 30% uncertain, 9% disagree.High-Skilled Immigrants (2013): “The average US citizen would be better off if a larger number of highly educated foreign workers were legally allowed to immigrate to the US each year.” - 89% agree, 5% uncertain.

High-Skilled Immigrant Visas (2017): “If the US significantly lowers the number of H-1B visas now, employment for American workers will rise materially over the next four years.” - 0% agree, 19% uncertain, 64% disagree.

The aggregated opinions of economists mostly reflect the evidence we’ve just examined. The typical economist is in marginal agreement with the idea that low-skilled immigration helps the typical American. The benefits are even clearer with high-skilled immigrants: they probably only drive down wages for the wealthier Americans they compete with, all the while providing professional services to everyone else and being more likely to patent new innovations. Creating and deploying those innovations means higher labor productivity and higher wages, though the distributional impact would vary by the type of technology.

I think I could do a good job at writing an encyclopedia. So, here is an imaginary Whitcombpedia entry on undocumented immigration and wages:

Theoretical reasoning and available empirical evidence suggest that undocumented immigrants, who are generally low-skilled, depress the wages of low-skilled native-born workers in the US, though this conclusion is somewhat uncertain. The long-run impact of immigration on the wages of the whole population is likely to be nonexistent or positive.

In theory, an increase in low-skilled workers should raise labor supply and raise labor demand, since the immigrants pay for products produced by everyone, including low-skilled natives they compete with. Because much of the income earned by the immigrants is spent on products in other industries, however, the increase in labor demand in their own industry is outpaced by the increase in labor supply. This theoretical result does not always hold, since low-skilled immigrants can complement the labor of the native-born. They may specialize in manual tasks while the native-born specialize in more language-intensive work, as in a study of refugees in Denmark where wages rose for natives. These are exceptions, however. The typical empirical estimate is negative but small.

Under the pessimistic assumption that immigrants and natives are perfect substitutes and labor demand does not rise to compensate, the lower wages that would result would also raise the returns to capital, encouraging greater investment until the ratio of capital to labor returns to its previous level. This raises the productivity of workers until the wage has returned to its previous level as well. These conclusions hold in the Cobb-Douglas model, but can be shown for any economy with constant returns to scale.4 Crucially, wages can rise for other reasons, such as technological innovation, so wages would not be expected to stagnate in the real world and may rise in spite of any downward pressure from immigration. This is what occurred in the US for the bottom 10th percentile of earnings from 1980 to 2023. At that part of the distribution, wages grew by 17% even while the immigrant share of the population more than doubled.

Evidence concerning deportations is mixed. In theory, these should raise wages for low-skilled natives through the reverse of the mechanism through which low-skilled immigration lowers their wages: supply shifts backward a lot while demand shifts backward only a little. Studies of emigration have generally found positive effects on those left behind, and deportation would have the same effect if it proved analogous. There are only a few studies of the effect of deportation on labor market outcomes for natives, and they have all found no positive impact or even a negative impact. Deportation may be disruptive in a way that emigration is not.

This is a bit rough. I could spend some more time adding links you’ve already seen and formatting them as encyclopedia-style footnotes. But needless to say, I think I should be put in charge. I’m disappointed in how both Wikipedia and Grokipedia assert confident conclusions where qualified arguments would be justified, and exclude relevant evidence pointing toward a different narrative. This is especially silly on the part of Wikipedia, since the actual, scientific point of view appears fairly liberal in the end, anyway.

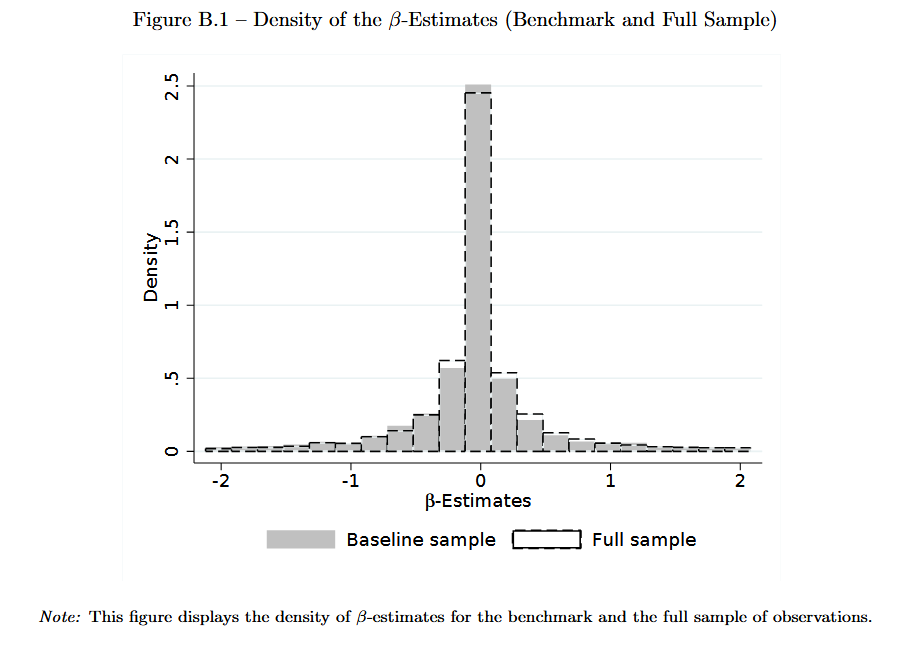

You might not have noticed, but in the Whitcombpedia entry I linked a meta-analysis from Aubry et al. not previously shown in this post, released in 2022. Within it is this plot:

This summarizes the standardized wage effects found in 64 studies published between 1972 and 2019. The typical effect is small but negative. (Where have I read something like this before?)

Interestingly, they state that “[…] without further evidence on this issue, identifying the true causal effect is beyond the scope of our analysis and of any meta-analysis in economics in general.” This is true for a variety of reasons, but what they really mean here is that they can’t identify the typical difference between native wages with immigration and native wages in the unobserved counterfactual cases where immigration did not occur. That’s true both because there are systematic biases in the studies that get published, and because even if there weren’t, we would still only know about the particular places we’re able to study, and that may bias our results, too.

What they are not saying here, however, is that their work reveals nothing about the causal effect of immigration on wages. If you would please consult the theorem:

The key insight here (quickly revealed if you spend some time plugging in numbers) is that some evidence E raises the odds that some hypothesis H is true if you are more likely to observe E when the hypothesis is true than when it isn’t. It seems pretty obvious that we’re much more likely to see a meta-analysis revealing that the typical estimate is only slightly negative if that really is true than if the real effect is usually very negative, as is often claimed. The only question is how much more likely, and I’d say “a lot”, whatever you’d take that to mean quantitatively.

With that aside, they also uncovered a variety of interesting patterns. Their conclusion holds for all skill levels: low-skilled immigration appears to hurt low-skilled native wages a teeny bit, and the same is true for high-skilled immigration and high-skilled native wages. Both the quality of the journal and the method used explained some of the variation in estimates, with diff-in-diff studies and high-quality journals tending to show more strongly negative results. That may explain why the typical economist is someone who is marginally convinced that low-skilled immigration hurts low-skilled native wages.5

Immigration debates will go on. If you wanted firmer conclusions about deportations, undocumented immigration, and immigration in general, you’re out of luck. But the case for more immigration, especially the high-skilled kind, appears very strong: we have good theoretical reasons to believe that high-skilled immigrants are helpful for everyone below their skill level, good empirical evidence for that conclusion, and evidence that they barely put a dent in the wages of high-skilled Americans, too, even in the short run.

In general, if you want an objective summary of an issue in economics or politics:

Expect that many of the questions you have simply will not have a firm, scientific answer. Issues become controversial for a reason.

Expect that some of them will have objective answers, and focus on the conclusions you can draw from those.

Do not use Wikipedia, Grokipedia, or any other text-based summary without expecting evidence to be at least someone selected. In fact, maybe just don’t use Wikipedia or Grokipedia in general. Take it as a warning sign if your source seems very confident about a controversial issue, and until you have seen literally every piece of evidence (you never will), try to say things like “it seems very likely” instead of “it is absolutely true” or anything to that effect.

Pray that you find a meta-analysis with a nice plot.

Here “spatial correlations” refers to how wages correlate with immigrants as a percentage of the population. These studies used city- and time-fixed effects to avoid omitted variable bias. You can read about those here on my blog or elsewhere.

Why care about theoretical tools for understanding something? There are two reasons I think you should keep in mind:

(1) They work in other contexts. The evidence available for any particular issue will always be smaller than or equal to the evidence available for issues it belongs to the same category as. If some theory works to explain those other issues that seem pretty much the same, it can help us understand everything. Think of how you might not have any direct evidence that your appendix exists but have a strong theoretical basis for that (other people have an appendix and you are like other people).

(2) Sometimes, evidence leads to obviously wrong conclusions. There is evidence that homeopathy works. If you want studies in top journals and randomized controlled trials confirming that bullshit is correct, that’s out there. It is wise, at times, to reject the evidence of the eyes for the evidence of the mind. (But of course, if you can make sure that the evidence is really good and there is no conceivable way anything has gone wrong, you should consider eating the bullshit.)

Don’t think that will stop economists from asserting their dominion over it, though. See here for an example of a paper written by economists on the subject of the connection between immigration and crime.

I’m not explaining things enough here, but this is a rough draft. (On that note, I now understand why Wikipedia articles leave so much unexplained—it’s overwhelming to try!)

To be clear about what I mean here: in the previously-mentioned survey, half of all respondents agreed low-skilled immigration hurts low-skilled natives. This tells you that if you sorted all of these economists from the most convinced low-skilled immigration hurts low-skilled natives to the most convinced that it doesn’t, the economist in the middle would be whoever thinks low-skilled immigration does hurt low-skilled natives but is, among his peers, the least convinced. (I apologize for how incredibly wordy the sentence you just read is.)