Economics Is a Science, Part 4

Coup de Grâce

Throughout this series, I’ve meant to seriously argue that economics is a science, but many still might think we’ve come up short. We’ve seen critical errors and difficulties: economists stuck in their ways, limited consensus on some issues, and evidence that most research papers are false, just to name a few. Some economists even admitted to fraud. I still believe that the ideas and methods of modern economics are scientific and worthwhile to engage with, and the evidence you’ve seen so far should show you why. But there’s a much stronger argument to give for a weaker but important claim, and it’s the one I believe this series should end with: Economics improves our knowledge of the world.

When I began studying political economy as a teenager (though I didn’t have that term for it at the time), I was first exposed to simplistic stories about the world, like those described in part 2. These stories can still be seen every day throughout social media, the news, and even TV and movies. Tariff policy is more often presented as a kind of battle of nations than a determination of what’s most efficient. Taxes turn into a drama club meeting, and everything else is likewise some battle of heroes and villains. Ideas become ideologies, astrological signs with no objective merit or truth behind them. Every bit of intelligence is reduced to a mere string of interesting phrases like intellectual sigils to ward off demons.

It helps to look at a specific example, so let’s consider how the political left and right confront the issue of tariffs. Usually, messaging on the right sounds like this:

This country has been scammed in its trade deals with foreign nations. Tariffs are how we take back our position in the world, bring jobs back home, and make America great again. They’re gonna pay for all we’ve done for the world.

And on the American left, through Kamala Harris:1

WASHINGTON — Vice President Kamala Harris called former President Donald Trump's tariff proposals "a sales tax on the American people" in an interview with MSNBC’s Stephanie Ruhle […] "I say this in all sincerity, he's just not very serious about how he thinks about some of these issues," she continued. "And one must be serious and have a plan, and a real plan that's not just about some talking point ending in an exclamation at a political rally, but actually putting the thought into what will be the return on the investment, what will be the economic impact on everyday people."

Shifting over to her alternative:

"We're going to have to raise corporate taxes," she said. "We're going to have to make sure that the biggest corporations and billionaires pay their fair share," she continued. "That's just it. It's about paying their fair share."

Neither one of these candidates presented a vision suggesting complete knowledge of economics, though Harris was right to point out that there is substantial pass-through of the burden of tariffs to consumers. Still, this isn’t always true. According to the head of the American University economics department, Kara Reynolds, “the 2018 [Trump] tariffs fell primarily on US firms – who didn’t end up passing a lot of the cost onto the consumers themselves.”2

Nothing that Trump or Harris said during their campaigns explained why we might see variation in tariff burden like this or even suggested it, at least not with the depth of an economist. As for corporate taxes, these are generally disliked by economists, and are only useful for the sake of political expediency. Here is The Economist on the subject:

In practice, firms may enjoy market power over either workers (in which case some of the cost of the [corporate] tax may be absorbed by wages rather than just profits) or consumers (who may face higher prices).

Ironically, the more left-wing tendency to believe corporations have market power over workers is exactly why you should be suspicious of corporate taxes advocated for by the same people.

Rob Norton of Econlib on the subject:

The corporate income tax is the most poorly understood of all the major methods by which the U.S. government collects money. Most economists concluded long ago that it is among the least efficient and least defensible taxes. Although they have trouble agreeing on—much less measuring with any precision—who actually bears the burden of the corporate income tax, economists agree that it causes significant distortions in economic behavior.

The idealized tax regimes discussed by economists have little to do with political expediency or narratives of rich and poor. They are instead built on models of tax burdens like the standard model of supply and demand, repeatedly checked by gathering evidence. My point in this final part is not that the economists are right, but that they are obviously putting more effort into understanding these issues than the typical person, building on and improving our common-sense ideas.

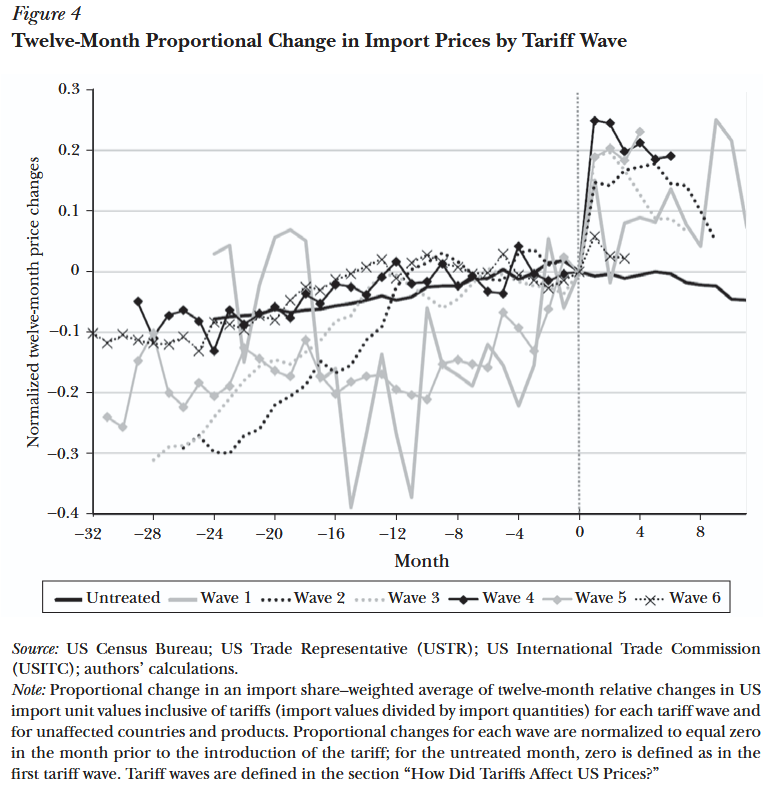

Consider this chart of import prices, where month 0 indicates the point in time when tariffs were implemented. The sudden jump in prices at that point could only be caused by the tariffs. It directly implies that Americans were paying more for tariffed goods, since they would simply not pay the higher import price if they could get these goods for the same price from American firms.

You can deny that there is scientific content in economics. You can talk about how economics doesn’t identify laws and could never hope to, or is plagued by bias. But there is no way, except through extreme ignorance, to deny that measuring the effects of these policy changes as explicitly as economists do is valuable and adds to our knowledge of the world. The same can be said of what we observed in part 2 in regards to the effects of immigration, alcohol taxes, and the minimum wage. Without those quantitative methods, and without economic theory either, we would be forced to become the bevy of camp-following whores, speculating about the effects using only storytelling and intuitions. If this paper were the only economics paper ever written, I would still call myself a fan.

For now, I rest my case. But it should be noted that by arguing about whether economics is a science or not, we’re merely arguing about how to summarize the field, not what the field really is. When we describe other fields like computer science as “science”, we create certain expectations about what can be observed about those fields, but no guarantees. We expect a selective combination of controlled experiments, quantitative measurements, identifiable natural laws, mathematical modelling, falsifiable claims, people in lab coats, etc. If we instead had a strict, expansive list of requirements for what counts as science, there would be no science at all. The inclusion of a single study with a single flaw would destroy the status of a field.

I found someone, Joseph Steinberg, who believes economics isn’t a science in part because economists can’t run controlled experiments (though he still endorses the field). First, this isn’t true. Economists like Vernon Smith have run controlled experiments to test the model of supply and demand, and other controlled experiments have been performed as well.3

Second, “you need controlled experiments for science” leads to an unexpected and undesirable conclusion: astronomy and astrophysics aren’t sciences, because you can’t run controlled experiments with black holes and brown giants.4 Defining science in this way misleads people into believing things like seismology and meteorology have a special quality that economics lacks.

More importantly, what this makes clear is that requiring controlled experiments in science can make some parts of a field count as scientific and not others. Even astrophysics has its narrower components with controlled experiments, with some laboratories attempting to simulate conditions usually found only in deep space.

Many other important features of science will fit certain subfields of economics but not others, or even certain papers within a subfield and not others. We can see a lot of “sciencey-ness” in the work of Vernon Smith, and perhaps the least in AJR’s paper on colonial development.5 This is not surprising. The same diversity exists in other fields like physics, where we can cleanly establish successful theories like Einstein did, and speculate about the universe being a mathematical structure like Max Tegmark. None of this should be construed as criticism of the less sciencey work; I think it’s all valuable. But clearly, how each aspect of each field is weighted in our judgment of whether it’s a science will vary from person to person. There might be some more objective way to do it, like looking at the most popular or well-cited work in each field, but our choice of objective measure is still going to be subjective. We can learn a lot by examining how economics might meet different definitions, but cleanly establishing a consensus on what does and doesn’t count as science in a way that fits our intuitions isn’t possible or particularly useful in itself.

So, whether you are claiming economics isn’t a science because it lacks controlled experiments, or claiming the same thing about some other field, you are inevitably making a summary claim rather than the strict claim you’re pretending to make. Misleading people like this is one of the most unscientific things you can do. It would be better to say “Economics lacks some scientific qualities other fields have”, but such a statement doesn’t have the punch people like in their rhetoric.

This leads into the last thing I want to talk about, which is why people so often dismiss economics as “not a science”. For the most part, I think the answer is obvious: economics leads to severely inconvenient truths about the world for most political and cultural ideologies. Left-wing types usually need to ignore evidence on the effects of price controls, while right-wing ideologies sometimes need to avoid acknowledging the benefits of public goods. The cultural left and right are mostly disinterested in economics, but the cultural right has views of immigration that often need to be sold to the public through lies about its effects on wages, employment, and crime. Bickering over whether economics counts as a science is usually not an academic discussion, but more an implicit discussion of how much respect is owed to the field. There are legions of people who don’t want much respect to be owed to it at all, and certainly not any amount comparable to the respect given to physics or even meteorology.

You might want some observations of this in action, and frankly, you can look everywhere. In Hungary, you can find the idea that high interest rates cause inflation. In Argentina, President Javier Milei runs a mostly wonderful economic agenda, but appears to believe that stimulus during a recession doesn’t work. And in China, the government has lifted billions out of poverty through free trade, but the Chinese Communist Party crushed investment in Jack Ma’s Ant Group to penalize his dissent.

Ignoring economists is a time-honored tradition around the world because governments and ideologies are rarely willing or able to act with benevolence. In general, governments serve their people only insofar as outcomes for their people impose costs and benefits on them that outweigh other interests. Porfirio Diaz, former President of Mexico, granted monopolies to supporters to maintain his rule, despite the obvious problems monopolies cause.6 He would not have created these monopolies if he knew he could be easily thrown out over poor performance.

Governments are most likely to follow the advice of economists in democracies, where they can only maintain power by appealing to all people equally, though even this is not enough at times. This is perhaps part of the reason why there is a strong correlation between measures of democratic institutions and median income.

I can’t provide a complete answer as to why political and cultural ideologies are so diverse and ignorant instead of closely adhering to the ideas of economists, but two reasons stand out. First, these ideologies are often taken up not as academic exercises, but because they appeal to our emotional attachments. Discussions around the book Abundance often involve people who care about climate change but despise the book because its solution to the problem is deregulation of clean energy construction combined with government action. Left-wing ideologies are often designed to reaffirm hatred of business leaders in the private sector, and anything that might benefit them naturally appears like a proper target for criticism, outcomes be damned. Similar problems occur when economists, being prototypical elites, try to advise those on the cultural right, who tell a story of American “managed decline” by its elites. But these are all only stories, not serious thinking, in the same way that supply and demand is only a story before you formalize it and check whether it works.

Despite having written so much about economics being a science, I’m forced to say that the battle was probably never about that. People will always have an incentive to ignore evidence that doesn’t favor their case, whether that’s an emotionally comforting story about landlords and corporations, or a political agenda that requires gathering support through favoritism. What economists hope to get from people isn’t rationality, but the benevolence to choose rationality. We can only hope they succeed.

The typical American leftist would identify Harris as a liberal, but I mean American left in the sense of where someone’s politics are positioned relative to the median voter. I don’t think “left-wing” has some abstract definition that works everywhere like Plato’s forms. Harris was generally perceived this way.

Taken from an email she sent to me in response to a request for information on the subject.

You might want to consider the AEA RCT registry:

https://www.socialscienceregistry.org/

By this standard, my field of study is more “sciencey” than Neil DeGrasse Tyson’s! I can’t accept that.

Acemoglu, Jackson, and Robinson, not the band.

Example taken from Why Nations Fail by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson.