In Severance, Mark Scout loses his wife and decides to “sever” himself to cope with this, working at Lumon without any memory of what goes on inside the severed floor of their building. Severance splits his memories into two: those of himself, and those of Mark S. Mark S. wakes up in an elevator to work at Lumon, works, leaves in the elevator and then immediately wakes up in the elevator again. Mark Scout, meanwhile, enters the elevator into the severed floor of Lumon every workday only to immediately wake up coming out of it.

Inside, Mark S. is doing… something. He leads a team that looks at computer screens of numbers, finds the scary numbers, and puts them in bins. The show is about a lot of things, but it could pass as a serialization of “On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs: A Work Rant”, the 2013 essay by anthropologist David Graeber.

Let me start by describing something most economists know about. In the United States and Europe, productivity has increased dramatically. We can produce a lot more stuff and many more kinds of stuff than we used to be able to. Every worker has a choice between leisure and consumption, where you work more hours to consume more, or you give up the extra income to have more leisure. In Europe, people have often chosen leisure. In the United States, people have often chosen consumption, so you get a decent gap in work hours between the US and Europe.1 People in the United States work about 31% more than people in Germany, on average. We also make about 20% more in income, on average.2

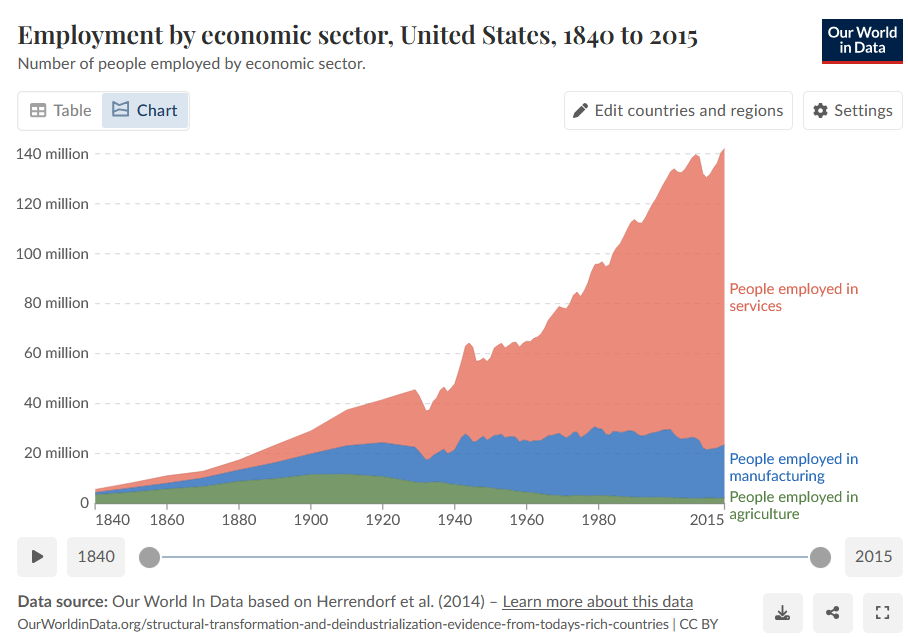

How does Graeber approach this? He claims that we have started working pointless jobs instead of taking advantage of increases in productivity to only work 15 hours a week (as economist John Maynard Keynes predicted we would), then claims that people haven’t really chosen consumption over leisure. Graeber describes another trend economists are familiar with: the decline of physical labor in the United States and the rise of service work and white-collar jobs. Calling these “bullshit jobs,” he gives the examples of financial service workers, telemarketers, and people in HR. He says capitalist competition is supposed to prevent the existence of jobs like these.

Graeber doesn’t provide evidence that these jobs have no purpose. He carries on with his explanation:

The ruling class has figured out that a happy and productive population with free time on their hands is a mortal danger (think of what started to happen when this even began to be approximated in the ‘60s).

What Graeber said here, unlike the jobs he complains about, is complete bullshit. People typically worked more in the 1960s than in 2013, not less!3 And that data in the footnote shows working hours have fallen continuously since the time of economist John Maynard Keynes, just not as much as he predicted.

Maybe my data is wrong. But rather than giving evidence, Graeber waves away concerns by saying there’s no objective measure of social value, then points to people who believe their jobs are meaningless. He gives another example: someone he knew when he was twelve, who became a poet, then a frontman in an indie rock band, then went into debt and had to become a corporate lawyer to get out of it. He says

There’s a lot of questions one could ask here, starting with, what does it say about our society that it seems to generate an extremely limited demand for talented poet-musicians, but an apparently infinite demand for specialists in corporate law? Answer: if 1% of the population controls most of the disposable wealth, what we call ‘the market’ reflects what they think is useful or important, not anybody else.

This is almost a valuable point. Your desires do weigh heavier on production if you consume more. But simply assuming the 1% is an evil cabal scheming to make everybody push pencils instead of doing a socialist revolution isn’t enough. You should actually check to see if that’s true. In practice, wealthy people spend more on luxuries like housing and entertainment, not man servants to do nothing but stand around and make them look impressive.4 Naturally, wealthy people also save more money.5

There’s also a simple explanation for why society would at times compel the frontman for an indie rock band to become a corporate lawyer. A single frontman for an indie rock band can serve millions of people simultaneously. A world in which many more people do a job like that is one in which people have exceedingly different tastes in music, never gathering around a single performer or band. That, or it would be an exceedingly inefficient world where lots of people work in indie rock even though everyone else would prefer if they’d do something else. Corporate lawyers don’t face the same problem, because plenty of companies face lawsuits at times and need many different lawyers to fight those suits.

You might question whether we need corporate lawyers. Corporations are powerful and have lots of money—why bother? If I wanted to defend corporations, I could give an (incorrect) example of an unjustified suit, which you’ve probably heard of. A woman spilled her McDonald’s coffee on herself and filed suit for hundreds of thousands of dollars. In that case, McDonald’s really should have had better standards for the temperature of their coffee to prevent that woman from spilling boiling coffee on herself: she was permanently disfigured.6

But a world without corporate lawyers is a world where you really could just make things up and sue a company out of business whenever you’d like. It’d be one where the costs of lawsuits make it impossible for a corporation like McDonald’s to provide the country-wide standardized products Americans like.

Maybe you think this is all just a byproduct of capitalism. But whatever form of economic organization you might imagine, we would certainly have rules and a need to adjudicate their interpretation, punishing wrongdoers.7 Lawyers are often safeguards against the needless punishment of whoever produces things. For example, Nike was once sued for $100 million by Sirgiorgo Sanford Clardy, because he claimed they should have sold their shoes with a product label informing him that they can be used as a dangerous weapon. (Mr. Clardy was a pimp. He was serving 100 years for repeatedly stomping on the face of a customer who tried to leave a Portland hotel without paying his prostitute.)

Moving on, Graeber names more examples of pointless jobs:

It’s not entirely clear how humanity would suffer were all private equity CEOs, lobbyists, PR researchers, actuaries, telemarketers, bailiffs or legal consultants to similarly vanish [he had pointed to how terrible it would be if e.g. all schoolteachers disappeared].

What I’d like to point out here is that much of the time Graeber is describing a pointless job, he’s avoiding details or explanation and pointing to highly specialized roles most people don’t understand because they’re highly specialized. Most only have the time to understand their own job. What does a private equity CEO do, anyway?

The answer is that a private equity CEO runs a company that acquires other companies that appear poorly managed, improves how they’re managed, then sells them at a profit. They may, for example, find an interesting chain of burger restaurants running at a loss. Then they discover that the burger chain just hasn’t spent as much as it should on advertising, and go on an ad binge. Now there are more people who know about the chain and love it, and the company is making a profit. So its value has risen, and the private equity CEO can make some calls and sell it to a new owner at a profit.

Any economic system would have a job like this or some other means of fulfilling the same purpose; ours happens to involve a jargony term for the job. A good commissar would make sure bad companies are reformed. As for the other jobs he mentions, they are at least arguably not pointless, leaving a lot of work for Graeber and his adherents to do:

Lobbyists represent organizations to the government. If you are part of a union, there’s a good chance your union has lobbyists that advocate on your behalf to the government. If you are part of an environmental organization, you probably have lobbyists advocating for things like carbon taxes. And yes, a lot of lobbyists work for corporations, and often advocate for things we don’t like, such as lower labor standards. But a world without lobbyists is not a world where corporations aren’t as privileged; applied without double standards, it’s a world where our connections with the government are severed. Eliminating one kind of lobbyist but not the other would require establishing a government agency with the power to decide who can and cannot try to persuade officials.

PR researchers figure out what the public wants out of their company. Presumably, they’re part of the reason why companies funnel money into charity and the like.

Actuaries are incredibly useful! They’re what allows an insurance company to operate effectively. If you’re unfamiliar, an insurance company takes money from a lot of people, and says “If any of you experience an unexpected cost, we can take money out of the pot to pay for it.” Insurance is a way for us all to avoid worries over one-in-a-million events. Actuaries figure out who is most likely to experience these events, so when you buy insurance, you get a discount for being on good behavior. If you’re not so likely to take money from the pot, you don’t have to pay as much. That makes the company more profitable and helps you, too. Of course, if you’re more likely to experience a terrible health event, you have to pay more, because insurance isn’t charity. We have actual charity and the government for that, and absolutely should fund those things instead of arbitrarily deciding insurance companies should foot the bill more than anyone else. In any case, it’s because they can charge people different premiums that insurance companies choose to cover so many people, which we want to happen. If you want to know more, you should read about price discrimination.8

Telemarketers don’t seem to really be in vogue now, but during their time they fulfilled the purpose of spreading information about goods and services people at times found valuable. Any form of advertising or marketing does also have some arguably negative effects in creating a barrier to entry for new competition (new firms have to spend even more on advertising to become as well-known) but Graeber doesn’t even bring in this point or talk about the optimal number or distribution of telemarketers. He just says they shouldn’t exist.

Bailiffs keep order in a courtroom. This one seems obviously important.

Legal consultants help people avoid breaking the law. Again, obviously useful, unless you don’t think laws should exist, or have some idea for how we can massively simplify the law without causing problems.

The jobs Graeber complains about are not pointless. They appear pointless because most people don’t have the time to try to understand the purpose of every job in existence, because in a highly-developed country, there are a lot of highly-specialized roles to fill. These jobs have a point—they give you lots of things you enjoy. Part of the reason (though not the primary reason) good restaurants pervade the US is because private equity CEOs keep them well-managed while legal consultants keep them from violating obscure laws.

Here’s a new proposal: the schemers you shouldn’t trust are people who take advantage of your poor understanding of the world to grab your attention and make you angry. There are people like this everywhere. They don’t care about providing evidence, they don’t know what the Federal Reserve Economic Database is, and they certainly don’t want you to know either. As soon as somebody avoids evidence and says anything like “You must agree—this is all just common sense,” you should run for the hills.

But so far I’m still coming up short. Don’t people still feel that their jobs are pointless at times? They do: Graeber inspired a YouGov survey confirming this.9 37% of British workers said they think their job is pointless. More surveys have been done to find the same thing in places like the United States.

My main point is that this is not because people are being lead around by their noses into doing pointless work. If there were a network of emails being sent around by rich executives saying things like “Make sure to tell Helly R. to put the scary numbers in the bins so she doesn’t try doing a socialist revolution,” a leak would appear pretty quickly just because of the sheer number of these people.

But knowing anthropologists, they’re more likely to explain this phenomenon with something akin to critical race theory, which points to racism in laws and rules rather than the behavior of individuals. So where are the laws and rules? Graeber doesn’t say.

Strangely, we have plenty of laws and rules that the ruling class decided to keep despite the inconvenience they pose to their plans: Medicaid, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and other forms of redistribution. For whatever reason they also want to make it as easy as possible for the poor to gather the resources for revolution, making guns more accessible here than anywhere else, and keeping the first amendment to the Constitution, which guarantees freedom of organization. Rather than a single, unitary government, any attempt at autocracy would have to wrest control of a federal system with 51 smaller governments interacting with the Feds, as well as all the local governments those smaller governments allow some independence within their own borders. Little about the US is consistent with the idea that it is some kind of oligarchy, except perhaps the voting behavior of politicians.10 We might just have the dumbest oligarchs on Earth.

On LinkedIn, you can easily find part-time jobs where you work the kind of hours Graeber describes and make as much money as the typical worker did in 1981.11 The question Graeber avoids answering is why people like me don’t apply to those jobs. Right now, I’m dealing with an annoying bout of unemployment after graduating. I could easily enjoy the standard of living of my young adult grandparents while working half as much as they did, so why not? Because I want to keep up with the Joneses, live in a nice apartment in downtown DC rather than a small house in the suburbs, eat out more often, and pay for nice vacations.12 You can make a good argument that constraining the rat race would make people less miserable, but instead Graeber just provides conspiratorial thinking.

But why do so many people in real life feel their jobs are meaningless? I never rebutted that idea—I’m sure people are being honest. We actually have some published academic work on the subject!13

Although we find that the perception of doing useless work is strongly associated with poor wellbeing, our findings contradict the main propositions of Graeber’s theory. The proportion of employees describing their jobs as useless is low and declining and bears little relationship to Graeber’s predictions. Marx’s concept of alienation and a ‘Work Relations’ approach provide inspiration for an alternative account that highlights poor management and toxic workplace environments in explaining why workers perceive paid work as useless.

Here’s more:14

…[there are modest differences in satisfaction] between classes, with those in routine and manual occupations reporting the lowest levels of meaningfulness and those in managerial and professional occupations and small employers and own account workers reporting the highest levels. Detailed job attributes (e.g., job complexity and development opportunities) explain much of the differences in meaningfulness between classes and occupations, and much of the overall variance in meaningfulness. The main exception is the specific case of how useful workers perceive their jobs to be for society: A handful of occupations relating to health, social care, and protective services which cut across classes stand out from all other occupations. The paper concludes that the modest stratification between classes and occupations in meaningful work is largely due to disparities in underlying job complexity and development opportunities. The extent to which these aspects of work can be improved, and so meaningfulness, especially in routine and manual occupations, is an open, yet urgent, question.

So it looks like even though there’s a meaningless jobs problem, it’s getting better, just as working conditions and incomes are. Not only that, the problem may be too little white-collar work, not too much!

Bullshit Jobs: The Book

Now for a counter-argument from Graeber himself, who expanded on his argument in his 2018 book Bullshit Jobs. I’ll cordon off some paragraphs so it’s clear where I’m providing an extended summary. The primary purpose of this part is to provide examples.

Better examples of bullshit jobs exist, with the author naming various categories of them. The first is flunkies, who do tasks someone else could easily do themselves. A woman named Gerte, when working as a receptionist at a Dutch publishing company, sat at a desk and answered the phone. She also kept a dish full of mints, wound a grandfather clock once a week, and managed another receptionist’s Avon sales (whatever that is).

Another category of bullshit jobs is goons, namely people in the military. One country only needs an army because other countries have armies. Similarly, companies only need lobbyists and telemarketers because others use them. Much of these jobs involve trickery. One visual effects worker described how he used trickery to make it look like different products actually work. [To add to what Graeber was saying here, cereal commercials often use glue instead of milk because it looks nicer.15 And it’s pretty well-known that fossil fuel companies peddle climate denialism.16]

Duct tapers. These people provide temporary fixes for problems that need a permanent solution. In the book, one of these workers described how he worked for a Viennese research psychologist who claimed to have discovered “the Algorithm”, a computer program you can talk to. He repeatedly found bugs, the researcher would say “oh… how strange”, then he’d fix them and voila, it works! But this kept happening.

Box tickers. They exist to make it seem like a company is doing something it isn’t. One of these people explained how she would record the entertainment preferences of residents on forms, only to file these away where they’re never seen. The only time she got to contribute to actually entertaining them was playing the piano before dinner. Another example comes from the author himself, who worked as a box ticker by sending scientific papers to lawyers who would pile them up in court when evidence was to be presented in medical malpractice suits. Nobody actually read them; they just might get inspected by the defense attorney or a witness at times.

Finally, there are taskmasters, who come in two types. Type 1 taskmasters assign work to others when they could easily assign it to themselves. Ben, for example, is a middle manager who claims to be such a taskmaster, though we don’t get any details about what tasks he actually assigns or why. Type 2 taskmasters make up work that doesn’t need to be done. Tania, for example, discovered that she couldn’t fire someone with a lot of seniority and good performance views, but needed a replacement. So she fabricated a new bullshit job that was really about cleaning up after them.

Graeber relies on the judgment of the workers themselves to determine whether jobs are bullshit, which is… questionable. Who would you ask to determine the value of ice cream: the people making it, or the people buying it? Certainly you could learn from both. Maybe the people making it will confess that sugar is addictive and they profit off of obesity. But the important part of determining whether it’s valuable is asking the people who buy it, who will certainly say they enjoy ice cream. And we’d expect someone to talk all about how making ice cream is meaningless if their pay sucked, they had no occupational mobility, and they knew we were uninformed enough to not know what use ice cream could possibly have.

But Graeber says this:

Unless one takes the position that there is absolutely no reality at all except for individual perception, which is philosophically problematic, it is hard to deny the possibility that people can be wrong about what they do. For the purposes of this book, this is not that much of a problem, because what I am mainly interested in is, as I say, the subjective element; my primary aim is not so much to lay out a theory of social utility or social value as to understand the psychological, social, and political effects of the fact that so many of us labor under the secret belief that our jobs lack social utility or social value.

This is a cop-out! If you go around saying “Most of the work we do is bullshit the 1% tells us to do!”, the only reason it’s an interesting idea in the first place is because we expect you to show that most work has no social value! It’s much less interesting if all you care about is “Well, a lot of people feel like their work is bullshit, even if other people want it done.”

And Graeber spends much of his time talking about social value anyway! If all that matters is how people feel about their work, why do you bother with “We only need armies because other countries have armies”? The phrasing “We only need…” directly calls on social value. Much to my frustration, popular work like Graeber’s tends to be a big motte and bailey, fashioning a decent argument and then presenting a more shocking and stupid version to draw people in.

I should add as a final note there was really only one class of people that not only denied their jobs were pointless but expressed outright hostility to the very idea that our economy is rife with bullshit jobs. These were—predictably enough—business owners, and anyone else in charge of hiring and firing.

Again, these people would be expected to know the value of the work they’re hiring people for better than anyone else. If you think they’re lying, you should provide evidence. You could compare companies with and without some common type of bullshit job and see if one performs better.

No one, they insist, would ever spend company money on an employee who wasn't needed. Such communications rarely offer particularly sophisticated arguments. Most just employ the usual circular argument that since, in a market economy, none of the things described in this chapter could have actually occurred, that therefore they didn’t, so all the people who are convinced their jobs are worthless must be deluded, or self-important, or simply don't understand their real function, which is fully visible only to those above.

Graeber doesn’t address that last point. Maybe the real function of a job really is fully visible to the person hiring someone to do it. We’d expect them to because it costs money to hire people. And yes, that doesn’t really show that the work people do isn’t bullshit, but there are far too many jobs in the world for it to be reasonably possible to show that they typically aren’t bullshit. That’s why you need a general argument rather than some case studies.

The examples Graeber gave are all easily explained, too. Yes, other people could have answered the calls the receptionist was answering. But these calls would have drawn them away from whatever they were working on, so the receptionist is able to let other people focus on their work and specialize in providing information. I don’t know what to say to the part about mints, except that they taste good and I always appreciated them as a kid.

World peace would be nice, and we would all appreciate not having to spend money on the military. But mutual disarmament is very hard. Doing so would involve convincing the South Korean and North Korean governments to trust each other enough to mutually disarm, rather than using it as an opportunity to take advantage of the other. The same would occur between Ukraine and Russia, Israel and Palestine, and elsewhere. You would also have to convince millions to voluntarily become unemployed. Every problem of “too many goons”, like too many people in advertising, is just a really hard collective action problem. These problems don’t have any special relationship to capitalism or a bullshit jobs phenomenon.

I don’t know how we might get rid of duct tapers, box tickers, and other bullshit jobs, except by outlawing inefficiency and lying. The thing about these jobs is that their costs are borne almost entirely by the people working them and the companies hiring people for them, so it’s not clear why we should care. Is there some reason to believe people are forced to work bullshit jobs for nefarious purposes? Again, we’re left in the dark on evidence for a conspiracy, and as we’ll see, he provides but one morsel of evidence in favor of this point.

Now we get to the chapter on why bullshit jobs are proliferating. Graeber thinks we haven’t noticed the rise of bullshit jobs because capitalism is supposed to prevent their existence. By that, I’m guessing he means “Pop culture notions about the economy suggest so, and I only took Intro to Microeconomics, so this is probably what economists believe too, right?”

I am not aware of any text in academic economics that suggests employers never make mistakes in a free market, or that labor allocation is always efficient. We have plenty of explanations for how things can go wrong, like a lack of competition or labor market frictions (e.g. search costs). Graeber doesn’t reference these ideas, and they don’t suggest receptionists and bailiffs shouldn’t exist.

Graeber almost addresses my concerns about conspiracism:

There has come to be a tacit understanding in polite circles that you can ascribe motives to people only when speaking about the individual level. Therefore, any suggestion that powerful people ever do anything they don't say they’re doing, or even do what they can be publicly observed to be doing for reasons other than what they say, is immediately denounced as a “paranoid conspiracy theory” to be rejected instantly. Thus, to suggest that some “law and order” politicians or social service providers might not feel it's in their best interest to do much about the underlying causes of homelessness, is treated as equivalent to saying homelessness itself exists only because of the machinations of a secret cabal.

This is an unfair assessment of the counterargument. Sure, politicians and social service providers might not feel it’s in their best interest to do something about the cause of homelessness. But Graeber is taking this a step further with his argument. He’s suggesting that they’re deliberately keeping bullshit jobs afloat throughout the economy, without providing evidence that this is happening. No secret communications, no leaks, no laws and institutions that explain the existence of bullshit jobs. He doesn’t even mention “tacit collusion”, which is taught in undergraduate economics courses, and describes how employers might stop competing and collude without explicitly agreeing to do so. And this particular example of tacit collusion is absurd: it assumes millions of employers cooperating not to hire fewer people like a monopsonist, but to hire more people and lose money in the process. A labor market cartel where successfully cooperating decreases profits.

I’m not going to be intentionally dense. The form of cooperation suggested here seems to be intended to maintain political power, not profits, through cooperation. But Graeber also doesn’t explain why this is the best way to do it. If you wanted to keep the public content, wouldn’t you employ them in meaningful work instead of the kind that makes them resent you? And indeed, that seems to be the direction we’re moving in anyway, as we saw before (“The proportion of employees describing their jobs as useless is low and declining and bears little relationship to Graeber’s predictions”).

Graeber says that nobody in a capitalist regime has sent out a central directive to create full employment through bullshit jobs. Then he says

…it is nonetheless true that at least since World War II, all economic policy has been premised on an ideal of full employment. Now, there is every reason to believe that most policy makers don’t actually want to fully achieve this ideal, as genuine full employment would put too much “upward pressure on wages:”

I’ll give Graeber a pass for unfortunate timing. He wrote this in 2018, two years before the pandemic led to exactly this policy being implemented. Unemployment spiked, then got pummeled into record lows by government policies that cut interest rates and raised spending. Inequality fell for the first time in decades and wage growth was strongest for the lowest earners.17

From my searching and reading his book, it appears Graeber provides only one piece of evidence, an anecdote, to show people with power are tacitly colluding to maintain bullshit jobs. Here’s Barack Obama talking about healthcare during his 2008 campaign.

“I don’t think in ideological terms. I never have;” Obama said, continuing on the health care theme. “Everybody who supports single-payer health care says, ‘Look at all this money we would be saving from insurance and paperwork’: That represents one million, two million, three million jobs [filled by] people who are working at Blue Cross Blue Shield or Kaiser or other places. What are we doing with them? Where are we employing them?”

The issue is that while his hypothesis (politicians deliberately create bullshit jobs to distract people) implies that someone would talk like this (“we need jobs!”), what matters is whether what Obama is saying here implies his hypothesis is true. It doesn’t, because it could also be explained by Obama being a savvy politician who wanted people to vote for him. With that said, what Obama was saying here was stupid and only works on voters. If we always protected jobs instead of firing people in the name of efficiency, we’d still be living with the incomes of the 1700s.

Graeber addresses an argument from The Economist that is essentially what I’ve said here. In response to Graeber’s essay, they wrote

Over the past century, the world economy has grown increasingly complex. The goods being provided are more complex; the supply chains used to build them are more complex; the systems to market, sell, and distribute them are more complex; the means to finance it all is more complex; and so on. This complexity is what makes us rich. But it is an enormous pain to manage. I'd say that one way to manage it all would be through teams of generalists-craftsman managers who mind the system from the design stage right through to the customer service calls-but there is no way such complexity would be economically workable in that world (just as cheap, ubiquitous automobiles would have been impossible in a world where teams of generalist mechanics produced cars one at a time).

No, the efficient way to do things is to break businesses up into many different kinds of tasks, allowing for a very high level of specialization. And so you end up with the clerical equivalent of repeatedly affixing Tab A to Frame B: shuffling papers, management of the minutiae of supply chains, and so on. Disaggregation may make it look meaningless, since many workers end up doing things incredibly far removed from the end points of the process; the days when the iron ore goes in one door and the car rolls out the other are over. But the idea is the same.

Graeber’s response is to hoist up some strawmen from weirdo libertarians (“the market is freedom and freedom is always good”, “bad results in the market are because of the state, good results are because of the market”) and ignore the specialization described by The Economist. Then he brings in a long example about universities as a refutation, which like the Obama example suffers from the problem of also being explained by something other than a conspiracy (maybe they competed themselves into higher administrative employment and can’t collude to reduce that employment because of the Sherman Act). The flaw in the reasoning here is analogous to omitted variable bias.18

I have poured over the pages of his book looking for more actual evidence for this eye-catching idea, but I can’t find any. I did find another funny parallel with Severance:

Simon: I spent two years analyzing the critical payment and operations processes at one bank, with the sole aim to work out how a staff member might use the computer systems to commit fraud and theft, and thereby recommend solutions to prevent this. What I discovered by chance was that most people at the bank didn’t know why they were doing what they were doing. They would say that they are only supposed to log into this one system and select one menu option and type certain things in. They didn’t know why.

More from Simon:

In my conservative estimation, eighty percent of the bank’s sixty thousand staff were not needed. Their jobs could either completely be performed by a program or were not needed at all because the programs were designed to enable or replicate some bullshit process to begin with.

In one instance, I created a program that solved a critical security problem. I went to present it to an executive, who included all his consultants in the meeting. There were twenty-five of them in the boardroom. The hostility I faced during and after the meeting was severe, as I slowly realized that my program automated everything they were currently being paid to do by hand. It’s not as if they enjoyed it; it was tedious work, monotonous and boring. The cost of my program was five percent of what they were paying those twenty-five people. But they were adamant.

I found many similar problems and came up with solutions. But in all my time, not one of my recommendations was ever actioned. Because in every case, fixing these problems would have resulted in people losing their jobs, as those jobs served no purpose other than giving the executive they reported to a sense of power.

Someone was in a position to observe lots of bullshit jobs and eliminate them, but couldn’t. I think smaller-scale explanations like these are correct and important. People really do keep their bullshit jobs because there are barriers to automation, like the union dockworkers who keep working for six figures because the ILA blocks attempts at port automation. And maybe executives really do enjoy having people employed under them. The textbook for the industrial organization economics class I took as an undergraduate describes exactly this phenomenon as an explanation for why mergers occur even though they usually aren’t profitable.19

But we already have solutions to this problem. Someone else can start a new company and compete with them. A private equity CEO could buy them out and lay off most of the staff. Graeber never explains why these solutions are insufficient, or how we could do better. And again, all of this avoids the question of “Is the 1% colluding, tacitly or through covert communication, to distract people by keeping them employed in bullshit jobs?”

Hitting ctrl+f for “conspiracy” led me to this footnote:

[referring to the Obama quote where he says he doesn’t want single-payer because it would destroy jobs] To those who accuse me of being a paranoid conspiracy theorist for suggesting that government plays any conscious role in creating and maintaining bullshit jobs, I hereby rest my case. Unless you think Obama was lying about his true motives (in which case, who exactly is the conspiracy theorist?), we must allow that those governing us are, in fact, aware that “market solutions” create inefficiencies, and unnecessary jobs in particular, and at least in certain contexts look with favor on them for that very reason.

Obama only stated his motive for not wanting single-payer. He did not make it clear why he was defending the insurance industry. Maybe they gave his campaign money, maybe he just wanted to give people a feel-good bit about protecting jobs while opposing a policy that might get him further accusations of being a socialist. And politicians being aware of market solutions creating inefficiencies while they continue to exist does not imply that they want those inefficiencies to exist. Those problems might just be hard to solve.

The really frustrating thing about Graeber’s argument is that there’s a lot to it I pretty much agree with. The number of telemarketers probably isn’t optimal because advertising workers in general create barriers to entry for potential competition. In addition, advertising often cancels out other advertising, creating a vicious cycle of useless competition. That could be solved by colluding on advertising, which is probably illegal under the Sherman Act, an otherwise great piece of legislation that makes cartels illegal.

I’d vote for single-payer healthcare if I could, even though I’d prefer something more like the Swiss system of private insurance combined with subsidized coverage for the poor. We could even achieve universal healthcare by just expanding Medicaid to cover the ~8% of people who lack insurance in the US. Graeber also recommends Universal Basic Income as a general solution to the bullshit jobs problem, which has been fairly successful in experiments, so I can’t help but agree.20

The short of it all is that Graeber is pretty much right, but overestimates the scope of the problem. The implication of rising bullshit jobs that serve no purpose would be inefficiency and impoverishment. But “Things are getting worse for the typical American” is one of the easiest ideas to refute out there.21 Some people do nonsense for a living and some jobs don’t need to exist. An Obama quote isn’t enough to show this is deliberate.

Popular Anthropological Thinking

Graeber’s way of thinking seems to be common to anthropologists like him, with what little I’ve seen of their field through a single college course and Graeber’s work. Now I’m in danger of committing the same sin I’ve often accused others of committing toward the field of economics, so I’ll hold my horses here and say that I don’t want to claim all anthropologists think in the way I’m about to describe.

I believe knowledge, the truthful kind, should be verifiably true and falsifiable, with a good degree of confidence. Because anecdotes are vulnerable to random chance and selection bias, it’s better to use large random samples and apply statistical techniques to analyze them.22

Alternatively, there’s what I’ll call the popular anthropological techniques. In ANTH-210 Race and Racism, the primary message of the course was complicated. First, race is socially constructed, decided by people rather than the physical world. In essence, this means that aliens would not be able to descend to Earth, look at the genetics of all humans, and notice clear categories that can be given names. We instead assign racial categories to different physical characteristics that tend to occur at the same time. The most important piece of evidence was this: no genes known today occur only within people of a certain race. And when, in Thind v. United States, an Indian man came before the Supreme Court and argued he was white because he shared a genetic lineage with white people according to contemporary science, they instead decided he was not really white, and not eligible for citizenship, because common sense dictated his race.

This is looking pretty good so far. If you want to verify that race is socially constructed, you need to do two things. First, show that it couldn’t be constructed from the physical world, ignoring human thought. We were given evidence for that, including a documentary showing that people can have more genes in common with members of another race than some members of their own. Second, show that it really is constructed by people. We were also given evidence for that in the form of Thind v. United States and many other examples.

The claims being made were limited enough to be supported by available evidence, making the arguments presented in the class very clean by my own standards. Stories and anecdotes work here because you don’t need anything better. Professor Burton didn’t claim people never decide someone’s race using genetics, only that because that isn’t always true, it must not be a purely genetic concept in practice. He didn’t claim that it’s impossible to construct racial categories using genetics, only that we aren’t doing that. The evidence for that is not really needed; the burden of proof is on someone else, who would need to somehow show there exists a system that divides people into different races using genetics and is popular either among scientists or the general public. The exception proves there’s no rule.

The problems often don’t come from any idea presented in the course being illogical or lacking sufficient evidence, but being too limited. You can believe in the core message of the course while simultaneously believing that black people generally have lower standardized test scores because they’re more likely to have genetic characteristics that cause that poor performance. In fact, you can believe that while also thinking much of the gap could be closed by improving the kinds of environments black people often grow up in.

The same problem occurred with Graeber’s ideas when he stepped back and said he does not intend to argue that bullshit jobs aren’t useful to other people, only that people don’t feel their work is meaningful. I wrote about the same issue in a blog post about ANTH-210. Here’s the first quote I used in the post, from For Antifascist Futures. This is not an anthropological work, but its field, American Studies, appears to overlap.

Drawing from these histories and present-day struggles, our invocation of fascism [to characterize leaders like Donald Trump and Viktor Orban] places various iterations of authoritarianism and state and extralegal violence directly in relation to racial and gendered capitalist crisis and the expanded reproduction of imperialism.

The authors wanted to show Trump and Orban were similar to fascists in certain ways. This is interesting, but it’s difficult to trust that the authors are motivated by a hunt for useful knowledge. We care about whether someone is a fascist or not because of the terrible things associated with fascism: deliberate attempts to kill all members of an ethnic group, invasions of other countries, and the quashing of important freedoms within the borders of a fascist state and its vassals. It would be useful to know if Donald Trump had plans to do any of these things. Instead, work is often done trying to show that he is similar to fascists in some more fundamental way most people don’t care about. Fascism is only used as a hook, not a warning about what people associate with the concept.

It might be useful to know that fundamental fascist features predict future behavior even if a politician doesn’t openly talk about genocide, but I have yet to see a case of genocide where the perpetrators hid their intentions until it was too late. The Nazis, for example, were very clear about their views of Jewish people and had long since made them second-class citizens before the Holocaust. For many years before the Holocaust, there were ghettos Jewish people were compelled to live in and yellow stars they were compelled to wear. Nothing like that is visible in the United States today.

Since the writing of For Antifascist Futures, Trump has been reelected and has threatened to do things associated with fascism. He has talked about moving all of the millions of Palestinians living in Gaza somewhere else and having the United States seize control of the area.23 He has talked about bringing Greenland and Canada into the United States, despite neither country wishing to join the union.

As President of the United States, he has the power to invade all of these places immediately. Nobody has a legal right to disobey him; they would instead have to rely on some other route. Democrats could convince the House of Representatives to vote to impeach him, then convince two-thirds of all US Senators to vote to convict him, and he would be removed from office. Alternatively, under the 25th amendment, Vice President Vance and the President’s cabinet could remove him by agreeing that he is “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office”, perhaps with some claim of lacking mental acuity, but this route seems shaky.

This is all to say that if you believe President Trump is a genuine fascist rather than an attention-seeking type, as those who enter public office tend to be, you must also believe that the Republican Party or some other force is restraining him. He has not invaded Canada, Greenland, or Gaza, and I am 99% confident he never will. I also haven’t seen any argument of this form—only claims that Trump is a fascist, which seem to be attempts at putting him in a bucket of bad guys to insult him.

I would sooner focus on the policies he has actually enacted, like banning transgender people from the military, which is both an ineffective form of leadership given their potential to contribute, and deeply unfair. Nobody has shown that transgender people are inherently unfit for the various forms of military service, nor have they shown that existing screening processes cannot stop the bad apples among them from getting in.

The point is not just that people shouldn’t lead with hooks to grab attention and then change their arguments. The point is that strategies like that belong in tabloids, not in the mouths of respected academics and intellectuals. Popular anthropological thinking and other forms of thought similar to it tell stories and provide evidence for limited conclusions. Economists, meanwhile, are usually working on extremely specific and quantifiable questions with sweeping implications, like “Does immigration affect wages for the native-born?”

When solid statistical evidence is available, it is much better to rely on that instead. There was a moment in ANTH-210 when I pointed out that even while appearing large, US aid to Israel is not enough to substantially improve living standards in the United States because of our massive size, pointing to the great cost of Medicaid and Medicare. The professor then claimed that healthcare is only so expensive because we have an economic system based on greed. Not only is it not verifiable or falsifiable to say that the economic system of the US is based on greed (i.e. the statement is too vague to be a good criticism), the cost reductions needed to dismiss my point would be on the order of ten times. There are no examples of an economic system where those cost reductions have been accomplished. Even the UK, where single-payer healthcare prevails, has per-capita healthcare expenditures that greatly exceed per-capita aid to Israel in the US. You cannot meaningfully better the lives of Americans with a fraction of 1% of all federal spending.

This post has wandered quite a bit. I suppose the message I’m trying to send here is that you should always look for sufficient evidence when it’s called for, like with Graeber’s work, and a lot of popular work has much more limited implications than it seems to at first.

https://www.careerchange.com/newsletters/working-standards-u-s-vs-europe/

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD?locations=DE-US

https://ourworldindata.org/working-hours

https://www.clevelandfed.org/publications/economic-commentary/2014/ec-201418-income-inequality-and-income-class-consumption-patterns

This is surprisingly hard to find information about.

https://www.richmondfed.org/research/national_economy/macro_minute/2023/mm_06_27_23

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liebeck_v._McDonald%27s_Restaurants#Burn_incident

Unless you’re an anarchist, but this post isn’t about you.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Price_discrimination

https://yougov.co.uk/society/articles/13005-british-jobs-meaningless

There’s been some work done which suggests politicians tend to vote for the interests of wealthy people, but I think more people should consider the possibility that this can be true at the same time that lower class people have a lot of power in the United States. It’s possible that wealthy people are capable of influencing the government to do their bidding in a lot of ultimately small ways while power remains democratic, just because a lot of people don’t care enough to do anything about it. What matters is that the progressive system of taxation and spending in force in the US hasn’t disappeared—perhaps because wealthy people know it would quickly return if they used their power and influence to get rid of it.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MEPAINUSA672N

Much of our material wellbeing is based on relative status. Consider how miserable you would be today if you were living with the standards of the 1% from 200 years ago: no antiobiotics so you’ll probably die of an infection soon, no electricity, no cars or planes. But hey, at least you won’t starve, and you can probably get your picture taken with one of the first cameras.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/09500170211015067

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-4446.12941

https://hls.harvard.edu/today/harvard-law-expert-explains-the-burger-king-false-advertising-lawsuit/

https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2021/09/oil-companies-discourage-climate-action-study-says/

https://cosm.aei.org/a-side-effect-of-the-booming-job-market-wage-inequality-is-way-down/ ;

This occurs when you want to know whether A causes B, but A is correlated with C, and C has some effect on B.

I am not sure if this remains true today. The textbook was Industrial Organization: Theory and Practice by Waldman and Jensen, 4th ed. Here’s a paper finding they tend to result in higher markups but not higher productivity, released three years after the textbook was: https://www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/feds/2016/files/2016082pap.pdf

https://basicincome.stanford.edu/research/ubi-visualization/

https://www.reddit.com/r/badeconomics/comments/15hi9nn/no_it_was_never_normal_for_one_person_with_a_high/

And by analyze I mean reveal the precise relationship between variables and how confident we can be that a result was not acquired by random chance.

Apparently he was under the impression that Palestinians would be happy to leave; I’m pretty sure the Palestinians just want their homes back.